|

|

||

|

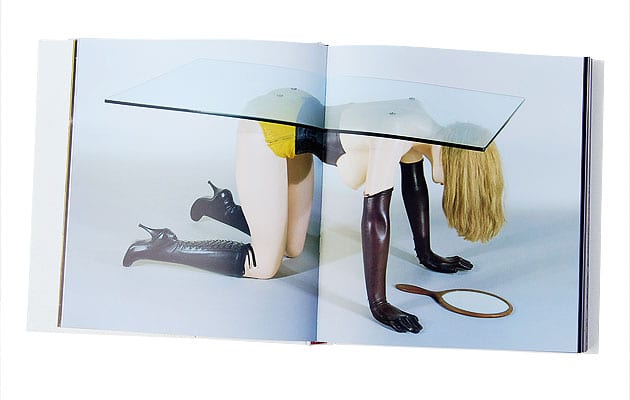

An arsenal of arses, a bounty of breasts and a lesser number of other female parts get enthusiastically ogled by Stephen Bayley in this bizarre book. We see the women, but where’s the design, asks Nina Power In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake suggested that “the nakedness of woman is the work of God”. In Woman as Design, Stephen Bayley, architecture and design correspondent for the Observer and former chief executive of the Design Museum, seeks to prove it. Inspired by a conversation with his wife over dinner (presumably oysters) about whether a modern product designer could handle the complex “mechanical,hydraulic and aesthetic problems” of the bit between a woman’s legs, Bayley has produced a gigantic, lusciously illustrated history of the parts of ladies that tend to excite and confuse (straight) men in equal measure. Clearly rather enjoying his topic, we are presented with an immense arsenal of arses, a bounty of breasts and slightly fewer, in Bayley’s own words, “ano-genital deltas” to pore over. Relating to Bayley’s initial jest “if woman is a design what exactly was the brief?”, a slew of somewhat Ballardian questions tumble forth: “Have any mortal designers ever achieved such an elegant and famous junction as that between the upper thigh and the gluteal mass?” “How can something so familiar equally also be so strange?” and, more critically, “Have we designed women?” Anyone concerned about objectification should probably look away. Andrea Dworkin (“the alarming feminist”) gets a mention, but Bayley reassures us that “to enjoy the woman’s body is not to exploit it; really it is about understanding and appreciating its design”. Well that’s alright then. But is this design heavenly or mortal? Bayley’s scattershot approach to the question – a bit of evolutionary psychology here, a bit of art history there – doesn’t seriously attempt to provide an answer, simply presenting his varied observations and findings according to whichever part is being ogled at the time. The section on “Above” entitled “Bras are for men or the industrialisation of the breast” is the most convincing, probably because it is here that the meeting of “natural” design and human artifice is most obviously traceable. Of the bra, he states: “This most womanly garment isolates, emphasises, moulds, packages and presents breasts in a fashion that men find desirable … In a bra, the breasts are designed: on delectable display, like a sandwich in an automat.” But it’s not all weird metaphors and pictures of Elizabeth Taylor’s bust. Anyone expecting a procession of pleasing images with a faint patina of intellectualised discussion may well be dismayed by some of the less immediately appealing images as Bayley also trains his eccentric gaze upon cow udders, primitive sculpture, ship propellers, dolls, oil reservoirs, chastity belts and nuns on scooters. There’s even a (mostly) naked picture of Beth Ditto in all her glory, accompanying Bayley’s claim that “men have always preferred the shapely and inviting callipygian curve”. If this is indeed the case, Bayley should have a word with the over-zealous airbrushers who staff women’s magazines. Oddly, considering who the author is, there is only a short section on how female anatomy has influenced design, including some bizarre ruminations about how Norman Foster’s sex therapist wife has made his buildings more curvy. It’s as if Bayley spent so long finding out about the history of breasts, buttocks and the other bit (“that neat detail when revealed becomes something both obsessively fascinating and existentially frightening”), that he ran out of room to talk about cars, table legs and buildings. Still, if you want to know why the 1958 Ford Edsel didn’t sell, Bayley will tell you. Hint: it looked too much like the “existentially frightening” bit and not enough like the curvier parts. Woman as Design: Before, Behind, Between, Above, Below, by Stephen Bayley, Conran Octopus, £50 For more projects from the Design Academy Eindhoven graduation show, pick up the December issue of icon, out soon. |

Words Nina Power |

|

|

||