|

|

||

|

Now open to the public, architect Konstantin Melnikov’s Moscow home was at the heart of a bitter ownership dispute that pitted its use as a residence against its value as a cultural artefact, says Charles Holland Back in August 2014, the remarkable house designed by Konstantin Melnikov in Moscow was seized by the Russian government. They evicted its tenant – an old lady called Ekaterina Karinskaya – taking possession of the house while she was out. This opportunistic act of eviction was done in the name of art. The house is now run by the Schusev State Architecture Museum and is, for the first time since it was completed, open to the public. There is a heavy political irony to this story. When Melnikov completed it in 1929, the house was one of very few privately owned residences in post-revolutionary Moscow. The architect’s family continued to own it throughout the communist period only for the house to be effectively nationalised under Putin. Ekaterina Karinskaya is Melnikov’s granddaughter and her continued occupation of the house has been the subject of a long and bitter dispute over its ownership and use. The ostensible reason the Russian state took possession of the house was to preserve it – Ekateriana was allegedly not looking after it and it had also become damaged due to nearby construction work. All of this raises an interesting question when it comes to the preservation and protection of important works of architecture. Unlike painting and sculpture, architecture serves a practical function. Houses are meant to be lived in, not looked at. The paradox at the centre of the Melnikov House saga is that, at a certain point, their status as art takes precedence over their use as architecture.

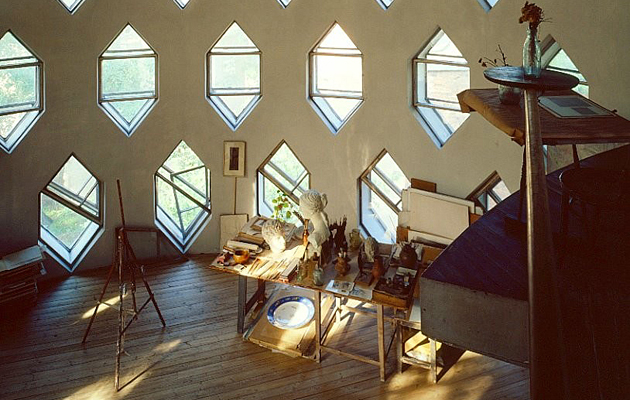

The Melnikov House takes its place alongside other modernist domestic masterpieces, including Adolf Loos’ Villa Muller and Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, both of which have become museums dedicated to their respective architects. Like Melnikov’s, these houses have been subject to the vicissitudes of time and occupation. The Villa Muller, for example, was directly affected by some of the twentieth century’s most dramatic political events, including Nazi occupation, the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution. At various times it has served as a family home, the office of a state publishing company and the headquarters of the Marxist-Leninists of Czechoslovakia. There is a photograph of the house, taken during its use by this last organisation, where a small fridge has been parked unceremoniously up against the famous marble walls of its living room. Not the world’s greatest aesthetic crime, but revealing of a different sensibility with regards to the villa’s status. In all these cases, perceived threats to the building’s fabric are used as a justification for its “museumification”. Not such a bad thing you might say, not least because they become accessible to the public. But it raises an interesting question in relation to the preservation of architecture. How should one restore something like the Melnikov House? Visiting it last year, a large part of its appeal was the sense that it had been thoroughly used and lived in. Not only is it full of the Melnikov family’s possessions, including remarkable paintings and sculptures from the constructivist/modernist era, but these objects are scattered around the house, as domestic objects generally are, rather than carefully formatted or arranged. The cracks in the plaster and the dusty wooden floors add poignancy to Melnikov’s radical and revolutionary design. This rarefied appreciation of the house’s history is probably of little comfort to Ekaterina Karinskaya, who was no doubt quite happy living there. But, culture has now deemed her house too important to be lived in. Adolf Loos once wrote: “Only a very small part of architecture belongs to the realm of art: the tomb and the monument.” Architecture has to be useless to qualify as art. The Melnikov House – like Loos’ own Villa Muller – has become both a tomb and a monument. In doing so it has left the quotidian world of architecture and definitively entered the rarefied realm of art. |

Words Charles Holland |

|

|

||