|

|

||

|

An unflinching exhibition uncovers how the city’s architects collaborated in a frenzy of Nazi urban planning, writes Laura Snoad Totalitarian regimes, the Nazis included, tend to use architecture as a tool for consolidation, whether making ego manifest through large-scale dick-swinging, or manipulating urban fabric to implement oppressive social objectives. For many years, it was thought that Vienna played only a minor part in the Third Reich’s aggressive planning activity, a myth debunked after an extensive research project made possible when the Klaus Steiner Archive was donated to the Architekturzentrum Wien in 2011. The resulting exhibition presents this wealth of primary material, while also taking considerable care to place Vienna’s construction programmes in the context of wider National Socialist agendas. The reasons why Vienna’s significance has been underplayed are complex. The scale of the Nazis’ architectural intentions was largely unknown, as war broke out a year after Austria was incorporated into the Reich in 1938. Many planning projects – including the creation of a grand axis to the Danube, the redesign of the 2nd and 20th districts, and the redevelopment of Heldenplatz and Rathausplatz – were never realised. In addition, the architects involved, keen to hide their complicity, made sure the plans were suppressed after the war. That is, until the 1970s, when Steiner, an architecture student dissatisfied with the Nazi-shaped hole he saw in the city’s architectural history, began contacting their widows and children. What Steiner uncovered was, in curators Ingrid Holzschuh and Monika Platzer’s words, a “veritable planning euphoria”, initiated when Hitler gave a speech at the Rathaus on 9 April 1938, during which he designated Vienna as the Reich’s “pearl”. Sympathetic to the regime or not, few architects, planners or engineers could resist a politically backed drive for innovation. Split into nine thematic sections, the exhibition explores this frenzy, from conceptual urban reorganisation to drawings for the city’s air-raid defences. Charts from the social studies carried out by planners demonstrate the drive to “optimise” the city according to Nazi doctrine, as do plans for the new “Greater Vienna”, an expansion of the city’s boundaries in order to offer the “German peoples” more space and wellbeing. Vienna’s importance as a transport hub, acting as a gateway to the south-east and allowing commercial exploitation of the Balkans, can be seen in infrastructure plans, while another section deals with the defence systems developed to protect the city from Allied attack, the flak towers of which are still visible today. Perhaps most unexpected is the National Socialists’ investment in Vienna’s thriving cultural scenes, a move presented here as an attempt to distract citizens from the city’s loss of political function by rebranding it as both the “capital of craftsmanship” and “house of fashion”. This involved the Nazification of the city’s cultural institutions (the 1939 Opera Ball and the Honorary Ring of the City of Vienna, for example), as well as proposals for new monuments to reinforce Austria as a mediator of German culture between east and west, not least in the shape of a new folk museum – Oswald Haerdtl’s architectural drawings depict ornate tapestries with floral motifs, handicraft-filled vitrines and the Nazi eagle insignia hanging above the door frames. Considering that much of the material on display needs considerable unpicking, the exhibition does well at contextualising the plans, sketches and documents, and highlighting their significance. Although the artefacts often belie the violent Aryanisation that they propose, Holzschuh and Platzer’s accompanying texts do not shy from the matter. Studio Toledo i Dertschei’s exhibition design complements this forthrightness. Propaganda films are projected onto drawing boards and texts rendered on tracing paper, while roughly rollered ply is the main means of construction. The result speaks of a history – and research process – still in the making. This is just the beginning of the uncovering of Nazi Vienna’s urban planning and, like the partially painted walls, it is a project far from finished. |

Words Laura Snoad

Vienna, the Pearl of the Reich: Planning for Hitler

Above: The City Plan of Vienna in the Year 3000, carnival party in the Künstlerhaus, 1933

Images: Archiv Künstlerhaus; collection Architekturzentrum Wien |

|

|

||

|

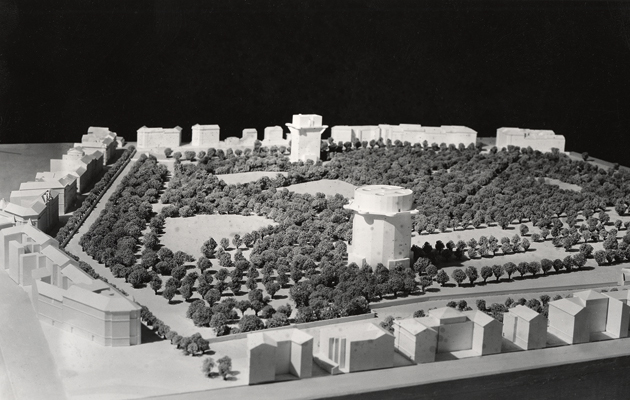

Flak towers in the Augarten, designed by Friedrich Tamms of the Todt Organisation |

||