|

Johnny Depp in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, 2005 (image: Tim Burton; Warner Bros) |

||

|

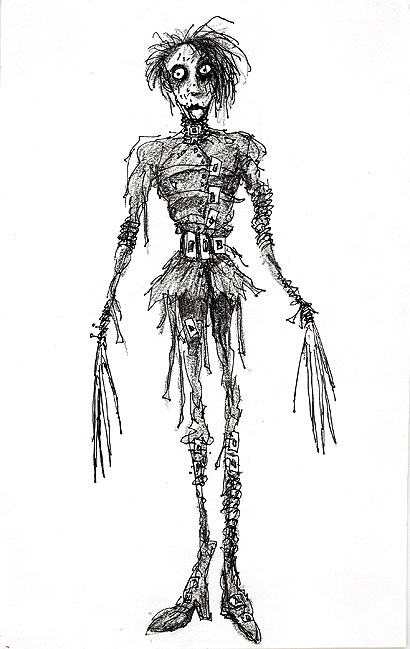

MOMA’s blockbuster on the gothic filmmaker packs in the material and oozes style, but is there anything else to it? Scott Geiger paid a visit Visitors to The Museum of Modern Art’s Tim Burton retrospective enter through a funhouse portal. One of the American filmmaker’s early sketches of a squint-eyed, fanged visage has been turned into the retrospective’s very busy gateway. Swallowed, you travel down this black-and-white striped corridor fitted with monitors screening animations. This orderly and stylish introduction opens into a gallery overwhelmed with Burton’s work in multiple media and far too many by-products from his films. Early drawings and paintings zigzag up and down the walls on one end of the gallery, while the opposite is crowded almost to the ceiling with memorabilia, figurines, costumes and props from the films. The foam-rubber jaws from Beetlejuice’s sandworm, for example, hang so high up on one wall as to be hidden there. Ron Magliozzi, MOMA’s assistant curator for film, has loosely structured the material around Burton’s biography. The intent is to describe the development of an auteur, the growth of his vocabulary and the escalation of an aesthetic from private sketches and writings into major works. Signage in the exhibit advertises three periods for the career: Surviving Burbank (his adolescence), Beautifying Burbank (his Cal Arts portfolio and Disney apprenticeship) and Beyond Burbank (everything else). Can we assume that Burton has worked happily ever after in an undifferentiated maturity for the past 25 years? Of course, says MOMA, ever since Pee-wee’s Big Adventure had its blockbuster opening in 1985. Yet the most compelling work precedes his feature-length debut. Two groups of drawings capture the start of Burton’s evolution from witty illustrator and animator towards a more complex artistry. Creature Series and True Love are incomplete projects he had on the side while at Disney, and both betray a novelistic curiosity for character and situation. Creatures encounter one another across a dining-room table; doors open; a wiry silhouette ascends a staircase. In one untitled drawing from Trick or Treat, dated 1980, there is an androgynous figure Burton has labelled “The Gardener”. Where his right hand should be are scissors. The drawings throughout this period are stocked with precursors for his cinematic characters. This is enough to validate Magliozzi’s project, and Burton’s process with some of his movies is at least hinted at here. Also impressive are two films Burton created in his early 20s for the Disney Channel. Both were aired as part of a 1982 Halloween-night special. First is a macabre animated short called Vincent, inspired by Edgar Allan Poe and narrated by Vincent Price. The second is easily the strangest piece in the show, a 35-minute Hansel and Gretel written and directed by Burton. Two Japanese children are trapped by a witch with a curled-up candy cane nose and dark glasses in an evil house brought to life by animators Rick Heinrichs and Stephen Chiodo. You take away from Hansel and Gretel the intensity of Burton’s prolific vision if not its consequence. The latter third of the exhibition is given over to the Hollywood films. Each is represented by a selection of drawings, paintings, puppets and writings generated by Burton’s creative process. A few intimate artifacts from his creative process are here, including a whole legal pad with notes on Beetlejuice – the word “Streamline!” is underscored – and his studies for Large Marge’s transformation in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. Then there are the severed-head props from Mars Attacks, the Batman cowls, the animatronic children from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. These are the by-products of Burton’s Hollywood career, and MOMA has chosen to conflate them with pieces created by his own hand. All we learn from them is that Burton is credited with the creation of the Hollywood films in which they were used. The volume of objects on display works against Magliozzi and his curators. Everything that is good about Tim Burton’s work, including that dark glamour Hollywood so adores, occurs here in too great a density. It reads as style loosed from substance or subject. This explains the funhouse portal and the topiary deer from Edward Scissorhands placed out in the garden. It may also explain why Tim Burton is now undertaking a remake of one of his own early films, Frankenweenie. If this show feels like the steady advance of a corporate brand across our cultural landscape, it is interesting to wonder who is at fault: MOMA’s curators or Tim Burton himself?

Michael Keaton in Beetlejuice, 1988 (image: Tim Burton; Warner Bros)

Edward Scissorhands, 1990 (image: Tim Burton; Warner Bros) |

Words Scott Geiger |

|

|

||

|

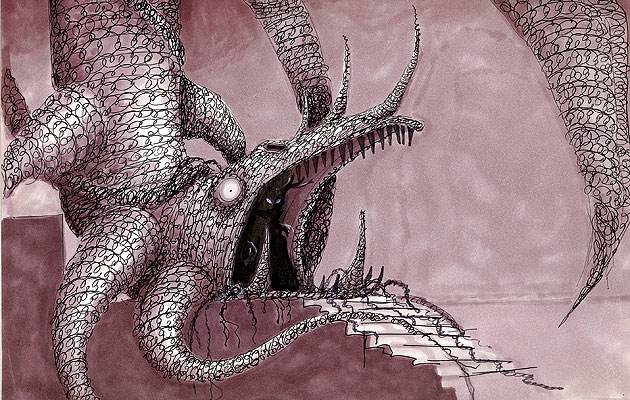

Untitled (Black Cauldron), 1983 (image: Tim Burton; Warner Bros) Tim Burton is at MOMA, New York, until 26 April 2010 www.moma.org/timburton |

||