|

|

||

|

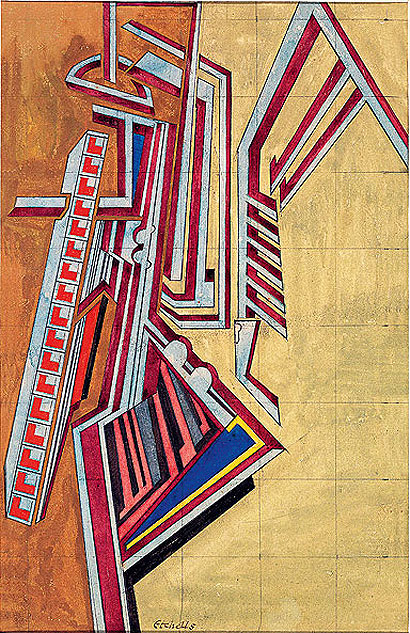

Britain has an unsolvable problem with modernism. Read the comments under any design or architecture article at, say, the Guardian’s Comment is Free, and 2011 can seem like 1931, with dozens of little Reginald Blomfields fulminating about those bolshy continentals and their modernismus. Apart from the post-war decades, which could be seen as taking in brutalism, punk, Archigram or pop, little has changed. Today, British modern architecture is pejoratively poor, a joke to other Europeans, but the situation wasn’t too different before 1945. When the “modern movement” (that is, the movement to unite art and everyday life that encompasses De Stijl, Soviet constructivism and the Bauhaus on the left, and Italian futurism and rationalism on the right) arrived in the UK, it was in exile. Central Europeans fleeing fascism stopped in Hampstead or Cambridge on the way to New York. We created our own versions, but they were of mostly local significance – Ben Nicholson a St Ives Mondrian, Maxwell Fry a provincial Gropius, Auden a camp Brecht. That’s excepting one incandescent moment – vorticism, which is now receiving a long overdue exhibition at Tate Britain. The thrill of vorticism, the furious and brief London movement that lasted, at most, from 1913 to 1920 but perhaps for no longer than two months from June 1914, is that it was both an authentic, insurgent avant-garde, with all the manifestos, all the extremism, all the flirting with politics and all the revolutionary aims that that entails; and that it was also totally, marvellously, insufferably English. That might sound odd, given that some of its prominent figures were American (Jacob Epstein, Ezra Pound, the pioneering abstract photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn) or even French (Henri Gaudier-Brzeska). But look at Wyndham Lewis’ rants and manifestos for BLAST, vorticism’s two-issue journal, helpfully printed on the walls of Tate Britain, and you’ll recognise a cantankerous sensibility and a splenetic, wilfully pompous, absurdist wit that is closer to Mark E Smith or Chris Morris than it is to Mayakovsky or Marinetti. Lewis did beautifully twisted, evil things to the English language, and similar warped things are done to the English landscape in vorticist paintings. The most important thing this exhibition does is reveal the breadth and quality of the latter, with obscure and impressive works from Frederick Etchells and Helen Saunders. Near the end of the Tate’s show, what is implicit becomes explicit, in that several seemingly abstract woodcuts by Edward Wadsworth are suddenly revealed to be figurative English scenes. The mills, chimneys and terraces clinging to the hills of West Riding towns like Cleckheaton, Mytholmroyd and Halifax are depicted as a true bedrock of modernism, a non-objective, anti-traditionalist architecture, intersecting with dramatic topography and gothic weather. In Wadsworth’s work of the 1910s, you can find more than a few hints of brutalism – something like the 1970s Halifax headquarters building is essentially one of Wadsworth’s dreams built six decades too late. At the same time, Wadsworth created port landscapes of equal drama, rendering faithfully the inhuman, robotic cranes and warships of Liverpool and Newcastle. Vorticism was probably the most advanced movement of its kind in the mid-1910s – it was as up-to-the-minute in its modernity as analytic cubism, De Stijl or suprematism. And in works like Lewis’ architectural tract The Caliph’s Design or Wadsworth’s Plan for a Vorticist Building (absent here) it’s obvious that their ambitions extended far beyond the canvas. Questions, questions, questions. Why did vorticism disappear so quickly? Why was it so easily forgotten? Was the horror it inspired in the press of 1914 at all justified? Was it a proto-fascist movement, like Italian futurism, or was it linked to the political unrest of 1913-14? What might vorticism’s air of simmering violence and dread-filled anticipation mean in the UK now, in a period of acute crisis? None of these questions are answered or even posed here. Much like Tate Modern’s recent futurism show, the curation is unimaginative – canvases, photos, the odd sculpture, with plenty of art-historical but little political context. The most impressive thing vorticism could be, it seems to argue, is a notable school of painting. It could have been so much more. The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World is at Tate Britain until 4 September 2011

credit British Council/The Estate of Frederick Etchells |

Image Tate Britain/David Bomberg

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||