|

|

||

|

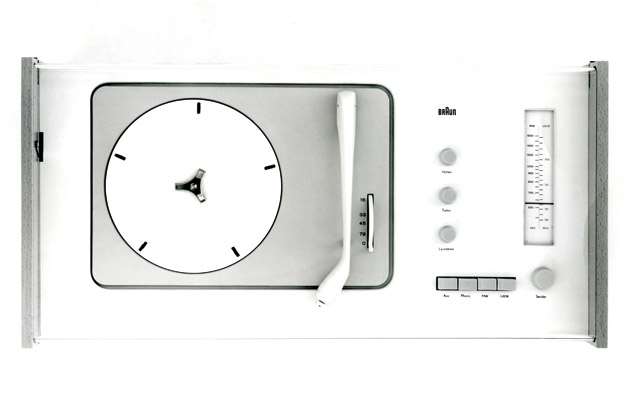

An exhibition tracing the influence of the German city’s industrial design school provides a welcome reminder of the appeal of radical pragmatism, writes Peter Smisek With the dissolution of the Bauhaus in 1933, the radical modernist experiment in Germany abruptly ended. With almost immediate effect, the school’s staff and students took their ideals abroad – to the short-lived Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Josef and Anni Albers helped educate America’s artistic avant-garde, or the various Ivy League universities that sheltered the school’s leading architectural thinkers. But in 1946, the Bauhaus mantle of industrial design returned to its shattered homeland, in the form of the Volkshochschule Ulm – renamed Ulm Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in 1953. The Ulm Model, an exhibition at east London’s Raven Row gallery curated by Peter Kapos, sheds light on HfG’s enduring influence. ‘The initial impulse for the exhibition was to offer a corrective to the view that Braun Design is the product of an individual’s singular vision,’ explains Kapos. HfG was involved with Braun from 1954 when the school’s founder, Otl Aicher, together with staff member Hans Gugelot developed the company’s visual identity. Dieter Rams only became Braun’s chief design officer in 1961, but continued the collaboration, and the many fruits of this are on show. Naturally, Braun looms large, but the classic SM31 shaver, designed in 1962 by Gerd Alfred Müller and Gugelot, is not the show’s only highlight. Student exercises, be they two- or three-dimensional, are exhibited in rapid succession alongside actual products commissioned by an array of corporate partners. It is an impressively broad portfolio, which demonstrates a strong commitment to a transdisciplinary process, involving designers, engineers, (social) scientists and manufacturers, with an explicit aim of streamlining production and enhancing the function – rather than style – of new products. Some, such as Hans Roericht’s TC 100 stacking catering service, designed as a graduation project in 1959 and taken into production by Rosenthal, or Gugelot’s 1963 Carousel S-AV slide projector for Kodak, became game changers in their own right. Instances of the Ulm stool, designed by HfG’s erstwhile rector Max Bill, are scattered around as occasional seating, and one is even on display, but it could have had a more prominent role in the exhibition as it singularly illustrates the post-war austerity from which the school sprang, as well as its fiercely functionalist and inventive streak. There are other notable omissions as well. Larger design objects, such as trains developed for Hamburg’s U-Bahn in 1960 and the Autonova family car from 1965, are not shown, even though the images feature in the thorough catalogue. One sympathises with Kapos, who chose to keep all displays life-sized, arguing that scale models lead to an estranged relationship between the spectator and the exhibit. But this, together with the plain white plinths used for display, means that the show feels more artful, and less than exhaustive in its scope. Despite the variety of objects on display, there is a high degree of kinship between them: a certain dryness, an economy of form and a severity that oscillates between minimalism and functionalism. The students’ exercises in photography and tessellation are imbued with more feeling, but not enough to approach exuberance. There is actually something incredibly appealing in designing objects as rational instruments, rather than relying on symbolism, association and personal branding, especially in the face of the current postmodernist revival and co-opting of design in service of lifestyle. Perhaps, one day, the Ulm Model exhibition could be adapted to a larger format, in a more expansive space, to give a more complete overview. |

Words Peter Smisek

The Ulm Model

Above: Braun’s SK5 radio and record player from 1958, in collaboration with HfG |

|