|

|

||

|

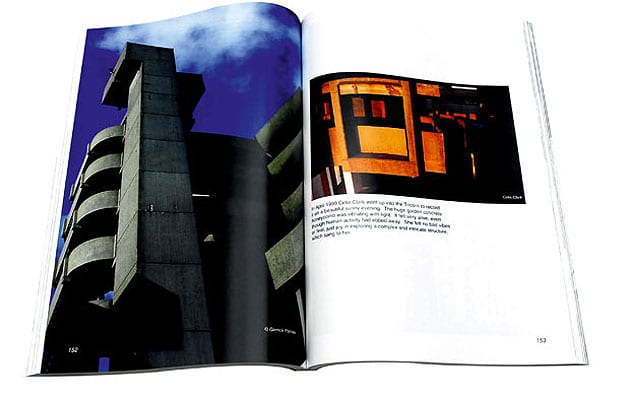

Labyrinthine and weird, the Tricorn shopping centre was a brutalist fantasy that was doomed to failure in 20th-century Portsmouth. Owen Hatherley enjoys a belated obituary. Architecture books are not supposed to be like The Tricorn: The Life and Death of a Sixties Icon. A celebration of a brutalist mixed-use megastructure built in Portsmouth in the mid-1960s and demolished in 2004, it is a scrapbook of quotations, with an efflorescence of images that range from gorgeous colour photographs to pixelly, low-res JPEGs. The content, while beginning and ending with the design and demise of the building, lingers on its everyday life over four decades. Regularly, ritually, voted worst building in Britain, the Tricorn was also passionately loved. Here, you can find praise from one of the original builders, an ex-New Romantic who used to visit its nightclub, skateboarding youths who remember “a concrete playground” and Noddy Holder. In short, we are not dealing with a book by Kenneth Frampton. The nominal designer was the commercial architect Owen Luder, a working class south Londoner, who unsurprisingly comments that “growing up as I did in rented rooms in tightly built Victorian terrace houses with no inside loo, I went along with Le Corbusier’s vision”. Meanwhile the designer who gave it shape, Rodney Gordon, was a young, mercurial aesthete, an AA student and GLC public architect who jumped at the chance to have his dreams made concrete flesh. Their brief alliance would create, among similarly staggering and mutilated buildings in Catford and Gateshead, a structure of such weirdness and complexity that it was essentially useless for its purpose: making money. None of the large companies that were intended to occupy the shopping space would do so, meaning that it helped bankrupt the developer and took on a life far more strange and intriguing than it would have had were it a success – something noted by the wonderfully named Proles for Modernism, who issued a communique claiming that “a spectre is haunting Europe … the spectre of the Tricorn – a symbol of demotic resistance that contradicts the role it was assigned. The concept of ‘functionality’ is negated in it”, instead providing a series of walks, vistas and enclaves. The Tricorn as reconfigured by its users comes across as a somewhat seedy place, where those excluded by the glossy malls congregated. We learn that Owen Luder’s favourite anecdote about the Tricorn was from “the woman who said it would always mean a lot to her because she conceived her seventh child inside it”. We find an artist using it for studio space stumbling across a pornographer’s set: “We went up to the top level and there was this young lady spreadeagled on a Ford Capri with this photographer snapping at her.” By the 1990s, after 30 years with zero maintenance, the building’s “functions” included LaserQuest, where “the labyrinthine spaces unfurled like clunky concrete experiments … an experience just like that you imagined when you played games on the ZX spectrum”. The local council and press hated it of course, and eventually got their way. There’s an underlying argument here that the place was always a glorious failure, a brilliant youth’s fantasy project that somehow mis-stepped into reality. One of the book’s many voices laments that “structures like this one haunt the passer-by from the realms of fantasy … but please, not in a small English island city”. It wasn’t provincial enough to survive. Yet this book attests to the physical, passionate feelings that buildings can inspire. “Architecture should give you that feeling from your balls to your throat,” said Rodney Gordon. The Tricorn did that, and this odd, moving book is an appropriate testament. Tricorn: Life and Death of the Sixties Icon, by Celia Clark and Robert Cook, Tricorn Books, £19.99 |

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||