|

|

||

|

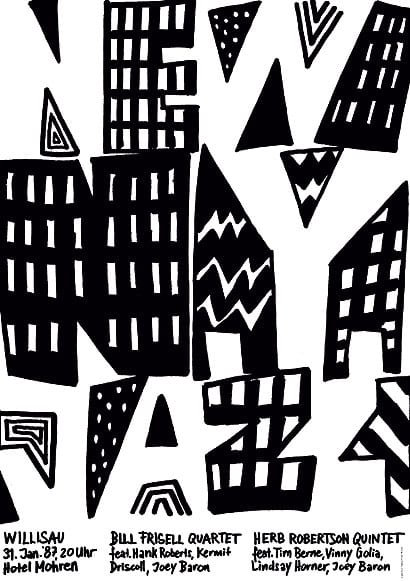

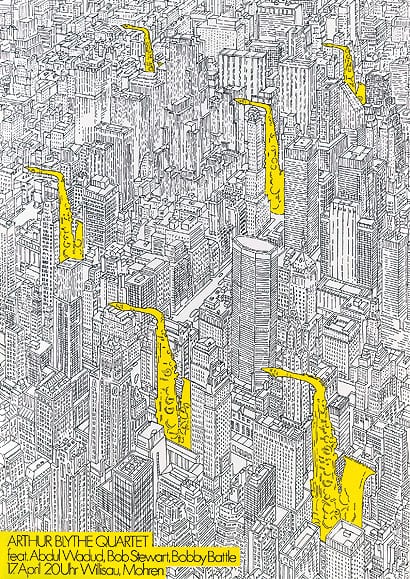

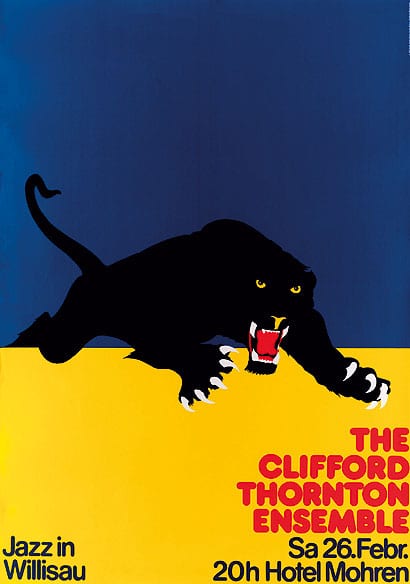

Once seen as part of pop music, jazz grew into its own cultural force and influenced everything along the way, writes Francesca Gavin. Rock ‘n’ roll has a big ego. It modestly claims to have revolutionised the world. But a more thoughtful look at the culture and visual expression in the 20th century shows that it was actually jazz that more broadly transformed the look of things, as the Jazz Century exhibition at Musée de Quai Branly in Paris shows. This sprawling exhibition located in the bottom floor is based around a 100m central timeline, with rooms opening off it like some giant spider diagram. Be prepared for an onslaught of imagery – sheet music, album covers, posters, art, film pieces and traces of the music itself playing out from small speakers built into the walls. As a sound, jazz was bold, brash, experimental and always moving. What jumps out of the show is how it revolutionised typography and graphic design, with the word itself seemingly dancing on the page. Before the advent of the gramophone record, the front covers of sheet music provided the first place for typographic experimentation, largely by anonymous graphic designers. The titles of now standard jazz songs in the exhibition, such as Crazy Rhythm and Rhyth-mania, look like they buzz and quiver. On the Fats Waller Favorites album cover the name breaks up, so each letter in Fats seems to head in a different direction. The rhythms and movements of the music found expression in the graphics, and words began to be imbued with more emotion and meaning, rather than existing as something decorative or explanatory. After the First World War, album covers provided a way to popularise some of the ideas behind futurism and type exploded on the page. It moved away from being calligraphic or florid to become something much more abstract. Linear expectations were broken up and words were allowed to vibrate. In the 1940s and 1950s the influence of jazz also spread to design. Album graphics became more experimental, with illustrators and designers such as Stuart Davis and an early Andy Warhol creating iconic layouts and images. Work by Josef Albers for Command records in 1959 and 1960 is particularly interesting as it transformed the shapes of constructivism into something popular and hip. This interrelationship between art, music and graphic design is plain to see. A short film of a Mondrian work about jazz is next to album covers reworking Mondrian paintings into graphics. Even if the connections are sometimes facile, it is still interesting to see how imagery becomes co-opted by popular culture. The exhibition isn’t faultless, though. The most obviously political period, the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s when African-American culture found expression is barely explained. Jazz was a revolutionary form of music and acted as propaganda. Its role in the social protests in the early Civil Rights Movement is never touched on – apart from the inclusion of Billie Holliday’s haunting Strange Fruit, which condemned American racism. But where are the references to the activism of Charles Mingus and his musical jibes segregationists? As jazz moved towards the end of the century, the imagery surrounding the music is less coherent. The graphics on poster and album covers in the 1970s and 1980s is more varied and messy in comparison with the stylishness cultivated in the 1960s. As the jazz became more improvisational and liberated so did some of its imagery. Cue album covers by Sun Ra and the brilliant collages Romare Howard Bearden. Elsewhere, however, it became more uptight and Germanic as seen in the posters by Niklaus Troxler for gigs and festivals in the 1970s. One of the highlights of the show is Adrian Piper’s 1983 film Funk Lessons is one of the most unintentionally hilarious pieces you will ever see. It depicts Piper giving Berkeley students a dance class alongside texts saying “White People Can Dance”. That might be the greatest legacy of jazz: the realisation that design could let go, be playful and dance.

The Jazz Century is at Musée de Quai Branly, Paris, until 28 June; www.quaibranly.fr |

Words Francesca Gavin |

|

|

||