|

|

||

|

A full-scale reconstruction of Ryue Nishizawa’s Moriyama House lays the foundation for a thoughtful, ambitious show at the Barbican, writes Peter Smisek. But the absence of metabolism is a structural weakness Japonism, the western obsession with all things Japanese, began in the mid-19th century as a wave of globalisation and imperialism forced the reclusive nation to open up to the outside world. Japan’s subsequent crash course in modernisation, militarism followed by pacifism, and its keen embrace of technology have kept the world fascinated ever since. It should also be noted that appreciation of the country’s architecture was always part of the package, seducing the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright and Bruno Taut. Even now, with architectural fads alternating between brutalism (on the wane) and postmodernism (on the rise), admiration for Japan’s ephemeral houses – they last 26 years on average – tends to unite professionals and fans alike in songs of praise. The latest exhibition tackling the subject is The Japanese House: Life and Architecture After 1945, currently on show at the Barbican Centre in London after a run at MAXXI in Rome. Given the immense popularity of the subject matter, and a slew of previous publications, it has a lot to live up to both in substance and in style. It is immediately evident that the show’s organisers are keen to deliver on the latter front, courtesy of Ryue Nishizawa’s Moriyama House (2005) in particular, which has been painstakingly rebuilt as a 1:1 mock-up in the gallery’s central space. For the uninitiated, the Moriyama House is, in the words of the curator Florence Ostende, a ‘radical deconstruction’ of the multi-unit house, in which the dwelling spaces, along with a few other programmatic components – bathrooms, an outdoor kitchen and a washing machine – are scattered seemingly haphazardly on an urban plot. The minute attention to detail (and styling) effectively immerses viewers and lets them imagine how life might play out in this highly unusual arrangement.

The work of Kazuo Shinohara highlights ‘the house as a work of art’ The second installation, a teahouse by the historian and architectural autodidact Terunobu Fujimori, while beguiling, falls short of expectations. Where the Moriyama House internalises the visitor in an imagined urban scenario, the charred-timber teahouse offers an inevitably disappointing view out to dimly lit gallery spaces instead of the intended bird’s-eye view of sakura-studded gardens and landscapes. Still, it does underline the important, if not always visually obvious, streak of traditionalism that underlies the design of Japan’s innovative domestic spaces. Accompanying this showstopper-and-a-half is a series of thematically and more-or-less chronologically organised exhibits that tells the story of Japanese domestic architecture throughout the last century by highlighting key personalities and tendencies. There are introductory nods to tradition, with accompanying photos of the 17th-century Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto that aid an understanding of the loose, dynamic spatial arrangement of traditional Japanese architecture. The Imperial Villa also served as a prototype for a surprising series of modernist houses built by the country’s avant-garde in the 1930s, which already displayed a merging of modernity with tradition. The high quality of the subsequent series of rooms dedicated to later decades and the ensuing societal shifts that informed the work of architects is slightly let down by a few omissions. The 1950s/60s room, for instance, does highlight the continuity with Japan’s pre-war domestic architecture and the search for new ways in which traditional features could be incorporated into modern living, but the curators could have opted for a more explicit depiction of the destruction left in the wake of US bombers. One of the most innovative houses of the period, Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sky House (1958), is featured but the exhibit fails to properly highlight the subsequent proto-metabolist transformations in which pods (‘movenettes’) and elements beneath the elevated ground floor were added and later removed when the architect’s children outgrew the house.

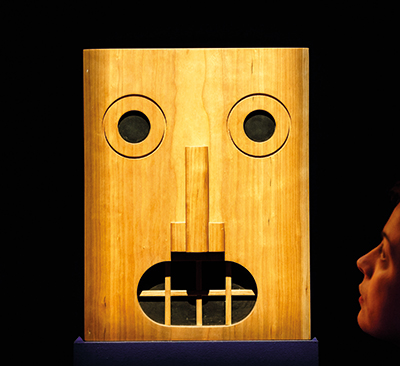

Face House, Kyoto, by Kazumasa Yamashita (1975) Sadly, this extends to metabolism as a whole, an architectural movement that is largely unexplored in the exhibition. The question is whether this makes sense – it was as radical an urban proposition as one could possibly wish for, and its most lasting built manifestation, Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972), attracts architectural pilgrims to this day. It is also notable that its protagonists were, for a time, veritable celebrities and put together the 1970 Osaka Expo, which, in tandem with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, helped to launch the country back onto the world stage. A more thorough inclusion of the movement would not only further elucidate the social condition of 1960s and 70s Japan – strict gender roles, relentless work culture, increasing consumerism, material prosperity and so on – but would also have given the exhibitors a chance to embrace a more accurate view of the country’s developing modes of urban living. In particular, it would have been much more effective to display the 1970s flirtations with seclusion and architectural autonomy against a more explicit backdrop of what was then the recent past. Similarly, it was partly the spirit of metabolism that helped the next generation of architects to embrace the madness of the metropolis in the 1980s. As such, it is not Toyo Ito’s Silver Hut (1982), but his later Pao: Dwelling for the Tokyo Nomad Woman (1985) – a series of radical furniture designs for the city’s fast-living population of emancipated women – that is the true heir to metabolism’s transient, utopian ethos. Even so, both exhibits are sorely needed reminders of an architectural era that the world has largely forgotten, and the importance of their inclusion cannot be overstated.

Sou Fujimoto’s NA House (2011) Additionally, the models, photographs and drawings in the exhibition are accompanied by a selection of films that illustrate not only the transitions in Japanese society, but also the architectural spaces in which these everyday dramas, from the believable to the absurd and the macabre, played out. But it is perhaps the inclusion of a trio of Studio Ghibli snippets, with their carefully studied settings, that provides a more colourful insight into the topic. Visitors should also not miss the new Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine feature, Moriyama-san, which documents a week in the life of the Moriyama House’s owner, landlord, artist, urban hermit and former liquor purveyor Yasuo Moriyama, and received its premiere during the exhibition’s opening. It runs for more than an hour, but is well worth the time, despite the missed opportunity of actually screening it against the pristine white walls of the Moriyama House, which is something the owner apparently does from time to time in his real residence. None of the other films on show, whether live action or animated, however, depict life in architectural ‘masterpieces’, pointing at another unfortunate omission – a frank admission of the utter banality of most of Japan’s housing, which is only ever hinted at, never stated outright. The Japanese House: Life and Architecture After 1945 is ambitious in its scope and thoughtful in its presentation. With the bar set so high, it just misses out on being the definitive exhibition on the subject, despite its many triumphs – the publication accompanying the Tokyo Metabolizing exhibition at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale is more comprehensive and presents a much clearer narrative of the evolution of Japanese urban and architectural form, and of the successive generations of houses. Nor, with the exception of the Moriyama House, has there been any attempt to include more communal housing projects, which have been gaining prominence over the past decade. Even so, there are more than enough new, valid insights to make the exhibition, and its thorough, accompanying catalogue, well worth anyone’s time. The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945, The Barbican, London, 23 March – 25 June 2017

|

Words Peter Smisek

Above: The rebuilt Moriyama House (2005) takes up the gallery’s central space |

|

|

||