|

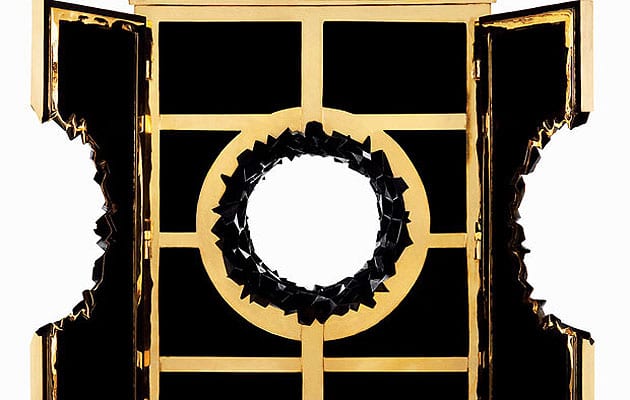

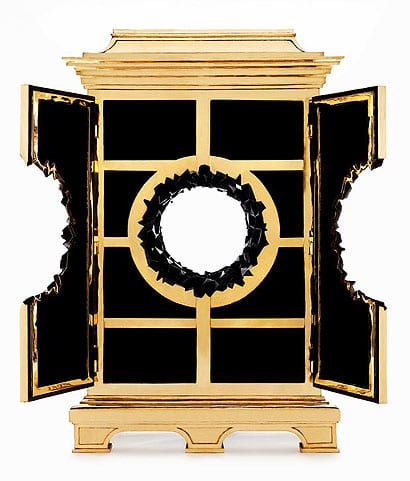

Robber Baron cabinet, Studio Job, 2006 (image: © Studio Job R Kot) |

||

|

Amid the V&A’s splendid heaps of baronial bric-a-brac, curator Gareth Williams’ Telling Tales feels as if it could be just another collection of historical leftovers, swept together to give us a taste of a disappeared age – The Magnificence of the Hedge Fund Managers 1999-2009, perhaps. Faced with something like Tord Boontje’s Fig Leaf wardrobe for Meta – a piece of furniture so extravagant you can get diabetes just from looking at it – it’s easy just to gawp. But Telling Tales has a message. Lots of messages, in fact – you can’t turn around without a piece of furniture trying to tell you something. What is it all trying to say? It’s a small show in the small space of the Porter Gallery, but the presentation makes the most of Williams’ selection of exhibits. The first two of three sections, the Woodland Glade and the Enchanted Castle, cover very similar territory – fantasy and opulence, seamed with darkness. From these rooms one gets the sense of designers suddenly free to indulge in as much luxury and ornamentation as they desired – in an almost judgement-free environment. Only Boontje and Marcel Wanders really seem comfortable in the milieu of excess. Other designers seem unable or unwilling to luxuriate without making knowing jokes and looking over their shoulders. Consequently the space is crowded with wry retakes of traditional high-value furniture, such as Jurgen Bey’s Pixelated chair and Gareth Neal’s George III dresser. It’s a place fraught with irony and double and triple meanings. At the apogee of this tendency is Studio Job’s Robber Barons series – a supremely strange and troubling set of furniture, like something from a gilded nightmare. In the Enchanted Castle, with its mirrored walls and fleur-de-lys decorations, surrounded by all these jokes and tricks, one thinks of masked balls and courtly battles of wit in ancien-regime Versailles – and one gets the same impression of a glittering world adrift on an ocean of insecurity. That insecurity gets probed in the final section, Heaven and Hell. The splendour is vanished, with the exception of the golden maggots that writhe in the ears of Kelly McCallum’s stuffed fox, the piece that stares sadly out of the show’s posters. There are sinister, fetishistic pieces like Atelier van Lieshout’s Sensory Deprivation Skull and Boym Partners’ Buildings of Disaster. These are viewed through peepholes, giving a visiting-time-at-the-nuthouse feel. One of the sharpest pieces here is Dunne & Raby’s Hide Away Type 02, a wooden box that the owner can hide in. Like the same studio’s cuddly nuke blasts, Lieshout’s skull, and the Boyms’ atrocity mementos, they explore design’s attempt to provide a means of escape, or ways of coping with a problematic and hostile world. Minus this last room, Telling Tales would just be a venue for rubbernecking at the excesses of the recent design-art frenzy. But with the addition of this dash of death and insanity, the exhibition looks more like an exploration of the psychopathology of the boom. You can see thoughtful designers casting around for meaning and trying to locate themselves in tradition in the meaningless, historyless new world of super-money – what emerges is desperate bling escapism and aesthetic abandon, in-jokes and gigantism. And everywhere there’s that sense of anxiety, the lengthening shadow of catastrophe. It’s a show with something for everyone: glitter for the gawpers, and portents aplenty for the apocalyptic.

“The Enchanted Castle”, including works by Jurgen Bey, Gareth Neal, Maarten Baas and Matali Crasset (image: V&A Images)

Robber Baron cabinet, Studio Job, 2006 (image: © Studio Job, R Kot) Telling Tales is at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, until 18 October |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||