|

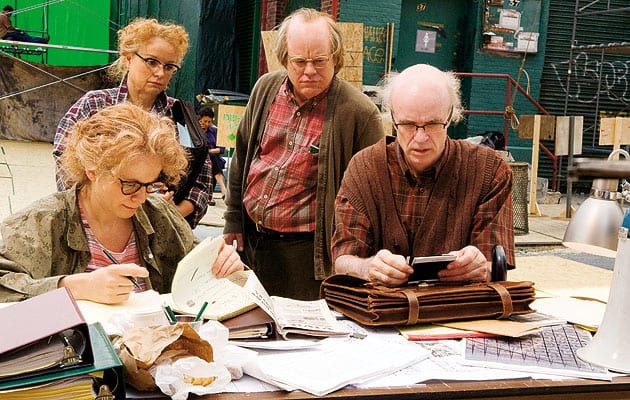

Cotard directs the replica Cotard |

||

|

A man builds a second Manhattan in a warehouse and wrestles with the big questions of death, truth and reality in Charlie Kaufman’s new film. It’s unforgettable, says William Wiles. Caden Cotard is a talented theatre director. But in other respects he’s falling to pieces. His doctors suspect there is something wrong with his brain, but can’t tell what it is. There’s blood in his urine, lumps on his limbs and pustules on his face. His marriage is even less healthy, kept on life support solely for the sake of his young daughter. His wife fantasises about him dying. He obsesses about death. Death is the other main character in Synecdoche, New York, Charlie Kaufman’s sprawling, enigmatic new film. With little but his talent going for him, and conscious of his co-star apparently waiting in the wings, sharpening his scythe, Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffmann) is awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called “genius grant” for exceptional creative individuals. He decides, while he has time, to create a theatre piece, one that is above all else “unfailingly true”. This work is the recreation of a chunk of Manhattan, built in a suspiciously large warehouse on that island and filled with hundreds of actors. This recreation is a beautiful thing to see on film: New York skyscrapers dwarfed by the industrial arch of the warehouse roof, with its rusty iron and grimy glass. It’s as if Buckminster Fuller’s proposal for a dome over Midtown had been realised using 19th-century heavy engineering rather than geodesics. Inside, planes fly and zeppelins float over multi-storey buildings that, in a shift of perspective, reveal themselves to be open at the back, with no more structure than scaffolding and plywood. It’s a fantastical and seductive vision, one of several in Synecdoche – one character, for instance, lives in a house that is on fire, a fire that burns for the 20 or so years spanned by the film. Synecdoche shares this merrily magical-realist approach to the built environment with Being John Malkovich, Kaufman’s 1999 cinema debut as a writer and producer. In Malkovich, a hidden door on the 7½th floor of a Manhattan building leads into the eponymous actor’s head. In Synecdoche, the microcosmic Manhattan inside the warehouse is doggedly micro-managed by Cotard as he struggles to make it match up to what he sees in his head. Teams work around the clock to fine-tune the streetscape, applying and removing graffiti and erecting facades by the plywood sheet. Cotard roams, giving the actors pointers. He hires someone to play himself, and follows around his surrogate, correcting his orders where they stray away from what he would do. But the quest for truth is quixotic. It brings to mind Jorge Luis Borges’ “On Exactitude in Science”, a cautionary tale of a map that is the same size as the territory it charts. At 1:1, the map is unusable, and is left to rot. Cotard’s microcosm is similarly useless. It cannot be as real as the real thing. It can only ever match what he sees as the truth, not a universal truth. It’s a stand-in truth, just as a synecdoche is a stand-in word – saying “the crown” to mean “the monarchy”, for instance. A crown is not a monarchy, it is just its symbol. And Cotard cannot figure out what his stand-in New York, filled with fake real people, is meant to symbolise. He doesn’t know what his “theatre piece” is for, or what to call it. His creation also grows more chaotic and repressive as time wears on and Cotard wearily attempts to maintain control before the final, final curtain. Synecdoche, New York is an unflinching and often bleak look at mortality, made palatable – indeed, unforgettable – by once-in-a-lifetime imagery. And its message, if not very uplifting, is at least necessary. We are all fixated trying to make this or that surface aspect of our lives perfect, obsessing over details while death gallops towards us.

The replica New York (image: Sony Pictures Classics) www.synecdocheny.co.uk |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||