|

|

||

|

At the end of last year, the Swiss voted to ban the construction of minarets. We asked architects to respond to the move, and suggest designs appropriate to a less tolerant Switzerland. Charles Holland

Office For Subversive Architecture

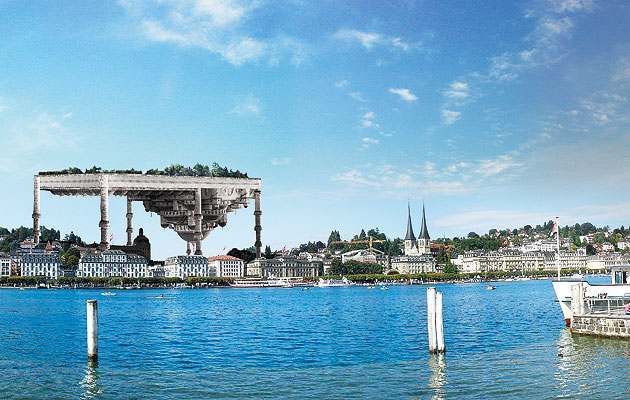

The official “Stop” poster campaign Bernard Khoury 15 March, 2012, more than two years after the majority of Swiss voters passed a referendum that banned the construction of minarets in the Swiss territory; the Imams of the four remaining Swiss mosques announce the construction of a demolition device around each mosque that mirrors the vertical architecture of their respective minarets. An open invitation is released to all Swiss citizens to participate in the annihilation of the remaining minarets. The device is aimed to translate this violence into an architectural act. This gesture emphasises the disappearance of matter in opposition to the tradition of erecting structures or monuments as a material manifestation of a political act. As such, the Imams are taking it upon themselves to write their own history by denouncing and physically translating the fears disseminated by the governing party. Celebrations, described by the international press as being an architectural “Ashura”, are taking place in Geneva, Zurich, Winterthur and Wangen bei Olten, where the four minarets in question are razed by the apparatus’ ferocious claws.

Julien De Smedt

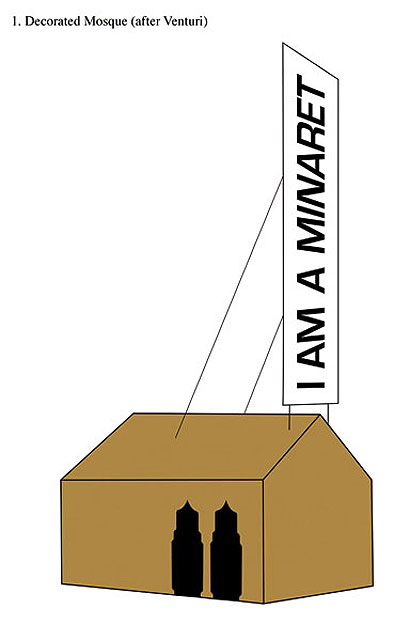

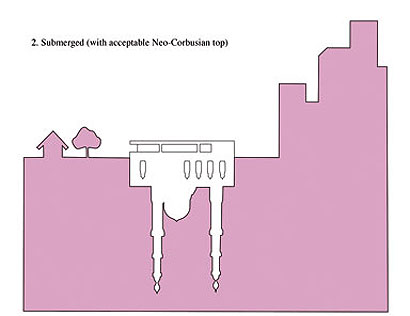

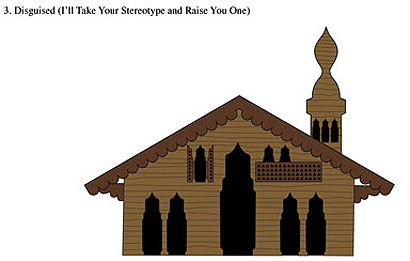

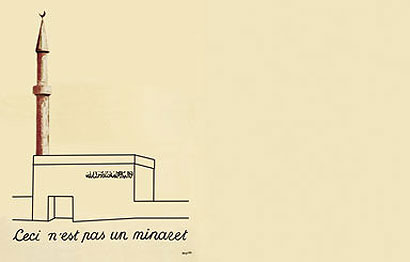

AOC When Magritte painted a pipe and wrote under it “This is not a pipe” he was highlighting the discrepancy between an object and a representation of that object. Our image of a minaret (from the Zurich mosque) is similarly labelled to highlight the creative potential of the discrepancy between a built form and the name given to that form. There is no official definition of a minaret. A brief survey of the world’s minarets, past and present, would suggest a formal diversity defying definition. Banning minarets as the Swiss have, without providing a formal definition, is somewhat problematic. To overcome the ban anyone wishing to build a minaret-like structure merely needs to name it differently. This is not a minaret, it is a spire / column / viewing gallery / ventilation shaft*. This approach is soon to be tested in Switzerland. The Islamic community of Langenthal have made an application to build a “tower” on their mosque, citing its inability to be used for the call to prayer as evidence that it cannot be deemed a minaret. Such conceptual creativity / legal fastidiousness* appears to provide the minority a useful opportunity to defend their buildings, and maybe even associated beliefs and practices, against the demands of the majority. * delete as appropriate.

Francois Roche

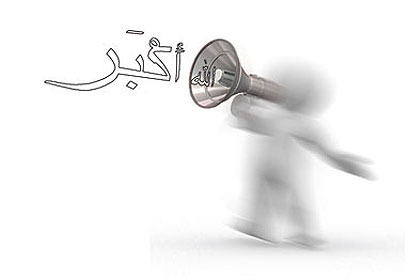

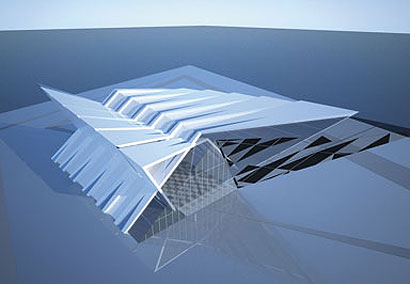

Street-level muezzin Saleem Jalil My design proposal primarily emphasises the ideology of monotheism and its importance in Islam. However, it also refers to the importance of the parts without which the whole ceases to function. The building sits on a platform, so worshippers approach indirectly, circling the prayer hall before entering it, a route that suggests the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. Water, an important element in Islam, is represented in the form of an urban water feature. This feature also serves as a wayfinding element indicating the two separate entrances for men and women. The space for women is equal to that of the men rather than secondary, emphasising the role of women in Islam. The whole architecture is derived from traditional forms including the minaret, but the result does not suggest a minaret to an observer. The building’s vertical structural elements point to the Kiblah – the point to which worshippers orient themselves for prayers. Finally, the internal structures provide a play of light and shadow suggesting a minimal but subtle ornamentation pattern.

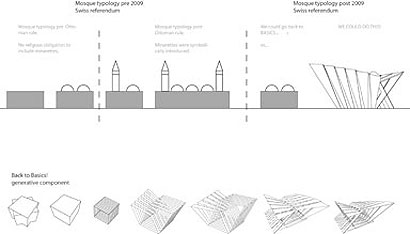

Left: Mosque typology pre 2009 Swiss referendum. Right: Mosque typology post 2009 Swiss referemdum |

|

|

|

||