|

Douglas Murphy asks what this year’s line-up for the prestigious award says about the state of British architecture Architecture is rarely a subject that makes headlines in the mainstream media, and when it does, it’s usually for negative reasons – high-rise ‘Towers of Terror’ in the 1980s, high-rise ‘Walkie-Scorchies’ today. This negativity is something that, over the years, Building Design’s ‘Carbuncle Cup’ has slotted into neatly, and its identity parade of dross has been rewarded over the years with plenty of coverage. Purely by being a reward for the best, the Stirling Prize is at a disadvantage, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t try to stir up its own controversies. Over the years, the Stirling has appeared to reward buildings as much for their political context as for the architecture itself, often in quite a finger-wagging, nannyish way.

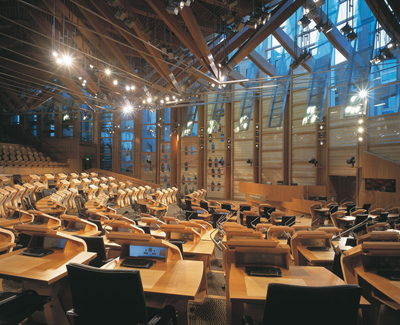

Evelyn Grace Academy (built in 2010) by Zaha Hadid Architects Zaha Hadid won in 2011 with the Evelyn Grace Academy – by no means her best work even if you like it, but this was within a year of the coalition government pointedly scrapping the Building Schools for the Future programme, so was widely understood as a lesson, as was AHMM’s Burntwood School last year. Similarly, in 2005 the Scottish Parliament was given the Stirling right in the middle of the political fallout over its catastrophic cost overruns.

Burntwood School (built 2014) by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Scottish Parliament building (built in 2004) by EMBT/RMJM Each year we read the leaves of the nominations in the hope of divining the mood beneath the award, and on first impressions we have to admit that the 2016 crop is equivocal. Michael Laird Architects and Reiach and Hall have created a fine college building in Glasgow with an admirably civic expression, while Loyn and Co’s private residence in Gloucestershire is lovely, in a Grand Designs kind of way. Two-time winner Wilkinson Eyre’s internal rebuild at the Weston Library in Oxford is perfectly nice as well. If I were a betting man, I’d say Caruso St John’s Newport Street Gallery for client Damien Hirst is likely to win, but again this is hardly an enthusiastic blessing – CSJ is excellent, but when the thing that is most praised about the building is the pleasant detailing of a staircase, then it’s hard to get over-excited. Two nominations suggest that eyes are off the ball with regard to politics, however. Herzog and de Meuron’s governmental school for Oxford, funded by not-exactly-all-round-good-egg Leonard Blavatnik, isn’t in line with the current mood, and is nowhere near the quality of the architect’s Tate Modern extension, which is worth a punt for 2017, perhaps.

Switch House at Tate Modern (2016) by Herzog & de Meuron Even stranger is the inclusion of dRMM’s vulgarly titled ‘Trafalgar Place’: middle-of-the-road developer housing built on the site of the Heygate Estate, whose social tenants have been ‘decanted’ and dispersed from their homes for the offence of not being rich. This is absolutely not the sort of project that should be winning awards. So in all, the message of 2016 is that Britain’s best architecture is perhaps a bit underwhelming, neither too blingy nor particularly challenging. Indeed, the biggest stink about the whole process is that FAT and Grayson Perry’s dazzling House for Essex didn’t get a look in. To be eligible for the Stirling, you have to have won an RIBA award first, and this building was completely ignored on that front.

A House For Essex (2015) by Grayson Perry and FAT This seems absurd for what is obviously important work, and one hears horror stories about the personal prejudices that local judges can bring to the RIBA table. So whether or not you think a hybrid artwork/villa built for a trite gazillionaire’s holiday home company is the best that British architecture has to offer, it shows that sometimes the fraught politics of architects passing judgment on each other’s work can come before the bigger stories. |

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|