|

Soviet postcard of Valentina Tereshkova (image: Poster Courtesy “Ne Bolta!” Collection) |

||

|

Nottingham Contemporary probes the space race in the imagination of communist Europe. By Owen Hatherley Let’s do the time-future-past-warp, again. Nostalgia for a time yet to come, the ruins of the future, the unexpected boredom of the 21st century – these ideas have been simmering for some time now, bubbling to the surface in books and mega-exhibitions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Cold War Modern show at the end of 2008. At best, it’s a way of making the past unfamiliar and casting the present in an unforgiving light, at worst a pseudo-political spin on museum culture, but regardless, this is an idea whose non-time has come. Star City is an excellent show, but contains within it this genre’s retro limitations as well as its possibilities. It arranges into (implicit) opposition a series of objects, installations and sculptures by mostly East European artists. The vintage posters and memorabilia remind us just how much “big tech” and the promise of space travel was part of the culture of the Eastern Bloc in its late 1950s/early 1960s pomp, before the region became a byword for backwardness. As this is a dead world, it’s experienced through the holes and hopes of memory. Sometimes this is a matter of age. Older artists such as the Kabakovs or Julius Koller pose as anti-authoritarian space travellers; but those for whom Communism is a hazier memory play with art and design history. So Goshka Macuga’s “abstract cabinet” – where an El Lissitzky assemblage is rebuilt and filled with space-age ephemera – presents the Soviet 60s as the unacknowleged fulfilment of the earlier avant-garde dreams, gone kitsch and mundane. Macuga’s material – wood – is everywhere here, and the new constructions are more “sustainable” than the old. David Maljkovic’s film about the fearlessly abstract partisan memorials of 1970s Yugoslavia is housed in a plywood constructivist box, and a ponderous remake of Tarkovsky’s Solaris can be viewed in a wonderfully simple and curvaceous cardboard auditorium, designed by Tobias Putrih. These lightweight miniatures take structures that would once have been in concrete and steel and make them flatpack, easily transported. This is only the second exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, reassuringly taking place in one of the few recent buildings to have suggested a new modernism that is neither pallid nor egotistical. The art works very well inside Caruso St John’s concrete spaces, but it creates its own inadvertent ironies. In one room, an installation by Micol Assaël, a hissing, decomposing machine, leads the eye through the strip window to Benson & Forsyth’s Ibis Hotel, a Malevich tribute of a similarly clever and retro nature to some of Star City’s exhibits. The best thing about Star City is that it’s an argument, an assemblage designed to make points about the ambiguous nature of the Soviet space programme – it suggests the idealism and the conformism of the era without resorting to the usual Cold War caricatures. The free exhibition guides are consistently intelligent without resorting to the piffle of contemporary art-speak, and the quotes that punctuate the spaces are pleasingly rich. When we find Malevich claiming that “the earth has been abandoned like a house infested with termites”, we think of environmental catastrophe as much as space travel, and on finding a large quote from the female cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova on her melancholic longing for a lost outer space, we might think of our predicament rather than hers. It’s not too far from us, though. Sometimes Star City is reminiscent of the weightless hypercapitalist fantasies scheduled but shelved after the 2008 crash – the dreams of a society that has no idea just how fragile it actually is. Yet it’s hard to imagine the future archaeologists of our age finding anything so poignant. Star City: The Future Under Communism is at Nottingham Contemporary, until 18 April www.nottinghamcontemporary.org

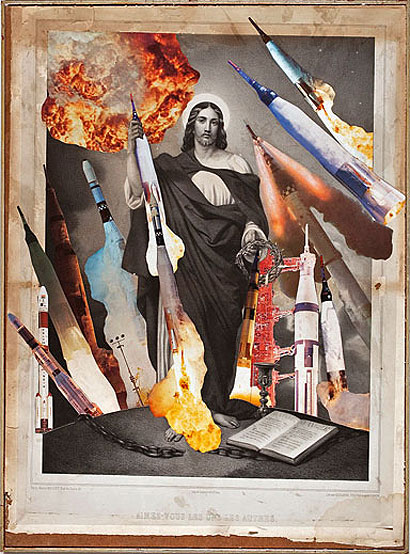

Aleksandra Mir’s The Dream and the Promise, 2009 (from series of 30 collages) (image: Mir Photo by Mark Baker)

Christian Tomaszewski and Joanna Malinowska’s Mother, Earth Sister, Moon, 2009 |

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||