|

|

||

|

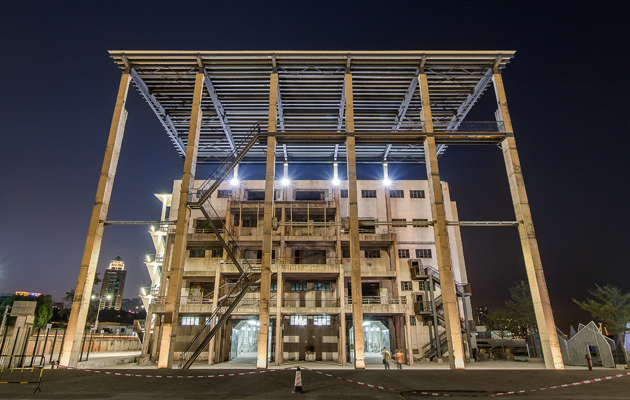

The architecture and urbanism festival calls for an end to the relentless churn of construction and challenges our thinking about city-making, but does it offer solutions for the future of its host city, asks Debika Ray? The Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture kicked off this month in a venue that is as much a physical manifestation of the event’s theme as a container for exhibitions. The event’s title, “Re-living the City”, is a plea to stop simply building more and, instead, consider how existing structures can better serve our needs. As co-curator Aaron Betsky said: “We have enough stuff. What we need to do is to reuse, rethink and reimagine what we already have.” To demonstrate this principal, co-curator and architect Doreen Heng Liu has overhauled the former Dacheng Flour Factory in the Chinese city to accommodate the main biennale activities, creating exhibition space, cafés and an auditorium, and opening up its grain silos to allow visitors to wander through their dramatic interiors. This year’s edition is perhaps hoping to replicate in the surrounding Shekou area the impact of its previous iterations on the city’s now-thriving OCT Loft creative neighbourhood. With a design museum under construction within walking distance from the flour factory, this process is already underway, but news that the main factory building may be demolished by the state-owned developer as part of its transformation into a mixed-use scheme somewhat undermines the biennale’s message.

Doreen Heng Liu’s Pearl River Delta 2.0 envisages a future for the region that balances globalisation with social and ecological priorities Still, the hands-on role of the city authorities in establishing and funding the event has by all accounts been vital to its success – and is indicative both of the Shenzhen government’s relative autonomy from Beijing and its willingness to critically engage with the problems associated with the city’s rapid growth. Indeed, the event’s thesis is an explicit critique of the Chinese fast-paced, paternalistic approach to development – a model that, in its short history, Shenzhen has previously been seen as emblematic of. Designated as the country’s first special economic zone in 1979, it has grown in thirty-odd years from a cluster of villages to a sprawling city of more than 10 million, thanks to rapid foreign investment attracted by its relatively liberal economic policy, low set-up and labour costs, and its proximity to Hong Kong. The exhibitions in this year’s biennale issue challenges to this relentless churn of construction from various angles. Liu’s Pearl River Delta 2.0, arguably the most successful of the three main exhibitions, presents a vision for the future of the region in which Shenzhen sits, centred around a balance between globalisation and ecological and social health – particularly pertinent, even prescient, given the tragic landslide on Sunday that engulfed 22 industrial buildings and killed many people. Among the best case studies on show is one that focused on areas at the fringes of urbanisation: Research into the quasi-rural Panyu area of Guangzhou examines how a juxtaposition of rural, urban and suburban forms could be an alternative to the linear trajectory of modernisation. More speculative proposals come from Chinese practices Urbanus and MAD: the first offers models for urban environments to accommodate young entrepreneurs; the second, a fantasy for a “forest island” on reclaimed land.

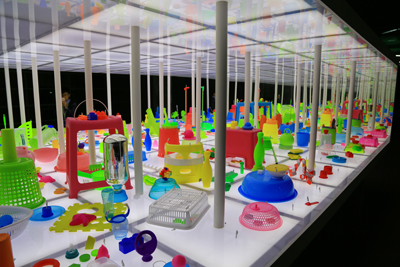

Jimenez Lai’s Lost & Found was a collection of objects made in China but purchased in the United States In his contribution, Collage City 3D, Aaron Betsky rejects grand utopias in favour of a layered approach to city-making. Installations made of cast-off materials demonstrate how new realities could be constructed out of old ones, from Rob Voerman’s migrant worker’s house to Jimenez Lai’s collection of objects made in China but acquired in the US. While aesthetically pleasing, the emphasis on visual impact over real-life projects and proposals arguably comes at the expense of intellectual engagement – after all, not all attendees were able to attend the associated symposium on the biennale’s opening day, where the work was discussed in greater depth. Here, the conversation touched on architecture’s sluggishness in adopting the sampling culture of contemporary music and the changing status of the maker. “Everywhere in pop culture we accept a sampled reality, but architects are still hung up on originality, endurance and ownership,” said Betsky. Slightly under-cutting this point, he slammed a secondary element of the biennale at another venue – the restoration of a traditional Hakka roundhouse to what he described as a “themepark” – as being contrary to his curatorial vision, discouraging people from visiting it. While interesting, the idea of collaging is not new. City-making through reuse, layering and adaptation has long existed across much of the developing world out of necessity, and it’s hard to escape the sense that such approaches are only considered radical when adopted by the architectural establishment. This concern is addressed somewhat by Radical Urbanism, the exhibition curated by Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner of Urban Think Tank, known for its 2012 Venice Biennale Golden Lion-winning research into Torre David, the skyscraper in Caracas informally occupied by more than 750 families until last year. Alongside UTT’s existing body of work, Radical Urbanism focuses on newer projects from architects with an activist bent and from outside the traditional architecture realm. Manuel Herz scooped the biennale’s top award with his images of the architectural forms developed by the long-term residents of refugee camps in Western Sahara. Interboro partners draw attention to lack of public access to New Jersey’s beaches, while Rahul Mehrotra and Felipe Vera focus on architecture’s temporal dimension, seeing events such as the 100 million-people Indian pilgrimage the Kumbh Mela as an architectural form, albeit an ephemeral one. While the policy implications of this “radical urbanism” – beyond deregulation and the raising of social-consciousness – remain unclear, the exhibition does provide valuable tools for critical thinking.

Manuel Herz won the biennale’s Golden Dragon award for his display, From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara In toto, the biennale’s displays convincingly express a conviction that the process of city-making requires as much consideration as its physical outcomes. This is certainly the case in Shenzhen, a city that continues to change. In one of the few national and thematic pavilions, the Victoria & Albert Museum presents work by the makers and technologists who underpin Shenzhen’s success, many of them having set up there because of quick, cheap and easy prototyping. Whether such advantages remain as wages rise and the “urban villages” vanish, will be a major concern, and will make pressing the need to envisage a different future for the city. Given the very real implications of the biennale’s propositions, it was therefore a shame to hear the phrase, “this is my first time in China and/or Shenzhen” so often during the associated talks. I would have been eager to learn more about the specific implications of the approaches advocated by either Radical Urbanism or Collage City for the Chinese context. Perhaps, though, the Aformal Academy, a programme of workshops and debates aimed at local students that will run alongside the event, will prompt the young architects of the future to answer these questions themselves. The Shenzhen Bi-city Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture runs until February 2016 |

Words Debika Ray

Above: The grain silos of the former Dacheng Flour Factory, which co-curator Doreen Heng Liu and her architecture practice Node overhauled to accommodate the biennale |

|

|

||

|

Building 8, which is hosting the main biennale exhibitions, may be demolished when the site is redeveloped |

||