|

Hotel Tropical Tambaú in João Pessoa, Brazil |

||

|

A documentary explores the radical designs that made Brazilian modernist, playboy and Niemeyer contemporary Sérgio Bernardes a star and the controversial affiliations that eventually left him bankrupt and forgotten, says Arthur Thompson “He was venerated back then – he was equally as important as Niemeyer,” says a colleague of Sérgio Bernardes in a documentary that premiered in the UK last week. “Back then” is the 1950s, when the architect, who designed his first house when he was 15, began a career that would see him become a darling of Brazilian high society.

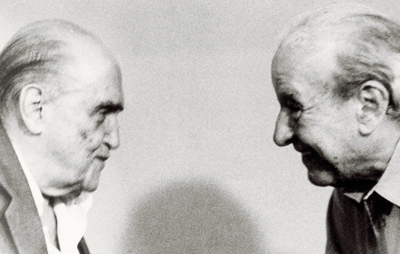

Bernardes with Oscar Niemeyer He was known for his elegant villas with rough-hewn materials, such as Casa de Lota. “Niemeyer’s houses were beautiful, but not comforting. Living well was Sérgio’s thing,” recalls a friend. The house, which he designed for fellow architect Lota de Macedo Soares, features an aluminium roof floating on lissom metal trusses. It won him the praise of Walter Gropius and Alvar Alto in 1954, when they adjudicated the award presented to him at the second Bienal de São Paulo. It was the first house in Brazil to use steel construction, at a time when the prevailing style of modernism favoured reinforced concrete.

Casa de Lota, Bernardes’ house for an fellow architect Bernardes is now the subject of a film pitched by his grandson Thiago Bernardes. As part of the family, he knew his grandfather as an important figure of 20th-century Brazilian architecture. This was a man who counted Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa as contemporaries and colleagues, has more than 6,000 projects to his name and designed 25 houses in one month. So, as Thiago Bernardes asks in the opening of the film, “why did they stop talking about him?” To answer this question, much like Nathaniel Kahn’s expedition to find the man behind the great Louis Kahn in My Architect, we learn about Bernardes – the womanising, car-racing (and -crashing), “misunderstood lunatic” – through the eyes of Thiago, who gives a secondary, familial narrative to a film that takes us decade by decade through the architect’s life and works.

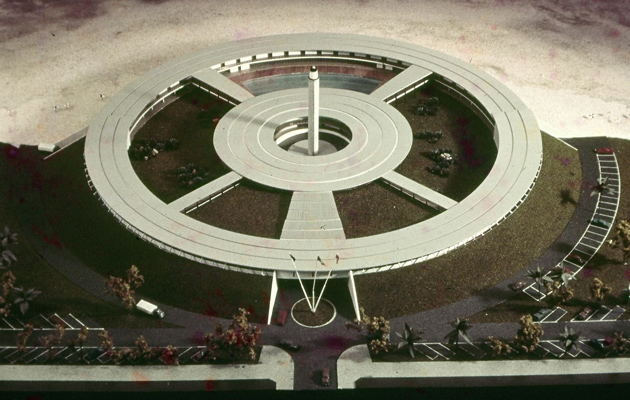

The Brazilian Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World Fair Bernardes always looked resolutely towards the future. He wished to “change how humankind live”, to the extent that in 1968 he left his family and wife of 25 years to travel to the United Stataes and meet fellow big-thinker Buckminster Fuller. He had grown tired of the high-life and his coveted family home in Rio de Janeiro, visited by the Kennedys, Os Mutantes and Bridgette Bardot (who was thrown out, screaming, by his wife when she was found in bed with Bernardes). He also abandoned a set of commissioned hotels when his plan for a dome over Hotel Tropical de Manaus, which would have created a jungle microclimate for guests, was rejected. |

Words Arthur Thompson

Bernardes, 2014

Images: Arquivo Sérgio Bernardes |

|

|

||

|

1965 designs for “Rio de Futoro” – a vision of Rio de Janeiro in 2000 |

||

|

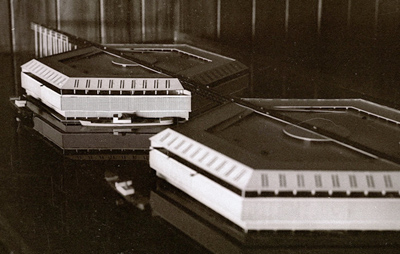

When he returned to Brazil, while many were fleeing the military dictatorship, we are told Bernardes “was working with abandon”. Although he was never a leftist like many architects of his generation, Bernardes seems to have been more naïve than complicit in his work for the government, seeing it as an opportunity to realise his ambitious urban designs. Also, “he wanted to revolutionise from within”, at one point believing he might shape the training of officers through his design for a military academy. Like many projects, it was never built and he eventually became a pariah to both the left and right. It’s implied, through the reticence of the interviewees when discussing this fertile period of Bernardes’ life, that his apolitical stance during the dictatorship might explain his relative anonymity today – not that Le Corbusier’s plans for Algiers or Rem Koolhaas’ CCTV building in Beijing has had much effect on their significance. He later set up a multidisciplinary research studio, Laboratório de Investigação Conceptual (LIC) – the spiritual antecedent of Koolhaas’ AMO – where he worked on developing architecture as an agent of change, drafting neighbourhoods with mile-high buildings to solve housing shortages, 30,000km aqueducts to bring water to north-east Brazil, and a bridge between Rio de Janeiro and Niterói supported by hotels.

Model for a bridge between Rio de Janeiro and Niterói supported by hotels In the 1980s, the architect declared bankruptcy on national TV. But, to Sérgio, no money meant no limitations. The film intimates that this creative liberation, coupled with obscurity, was the result of a man determined to be free of the moral and bureaucratic decisions that architects are forced to make. Throughout Bernardes, the filmmakers make extensive use of Sérgio’s drawings, models and manuscripts, which give the film a critical cadence, punctuating it with radical ideas and the deep hues of purple and green that feature in his Rio do Futuro designs of 1965, depicting Rio de Janeiro in the year 2000. It adds a shade of irony, however, when we are informed that “more than once he wanted to put the whole office archive on fire”. Sérgio Bernardes maintained that “the future is our biggest secret”, but I think posterity will be thankful that this forgotten modernist-cum-pyromaniac failed in his attempts to erase the past.

Bernardes’ rejected plan for a dome over Hotel Tropical de Manaus, which would have created a jungle microclimate for guests

Official trailer of the documentary This film was screened last week at the Barbican as part of the Architecture Foundation’s Architecture on Film series |

||