|

The Chancel and Crossing of Tintern Abbey, Looking Towards the East Window, JMW Turner, c. 1794 (image: Tate Britain) |

||

|

Isabel Stevens finds humour, fear and melancholy among the rubble as Tate Britain explores our abiding obsession with decay Why don’t building sites elicit the same fascination as ruins? Cranes are beautiful, awesome structures but they don’t have nearly the same hold on the imagination as crumbling walls and shattered windows. The bombastic opening room of Tate Britain’s Ruin Lust survey shows ruins in full seduction mode, turning you into one of those tiny figures in a Romantic painting trembling at the surrounding spectacle of wreckage. On one side, John Martin’s hellish vision of Mount Vesuvius erupting depicts civilisation in the throes of ruination. On the other, a forlorn Hadleigh Castle is painted in a flurry of brushstrokes by John Constable as if to further blur the boundaries between the walls and the plants that are overtaking them. Straight in front, the entrance to the Nazi battery at Azeville in Jane and Louise Wilson’s monumental monochrome photograph looms like a void waiting to swallow you up. Collated largely from Tate Britain’s own collection, this is not a definitive global survey. Instead it’s a show that highlights how decayed objects and structures are a recurring concern for British artists working with the landscape and the varied responses such longings provoke – some fatalistic or surreal, others comical, mournful or downright hubristic. Much of the exhibition’s intellectual framework will be familiar to those who have followed its curator Brian Dillon over the years (not only has he written extensively on many of the artists collected here, he is also the author of a book on ruins). Even so, there are plenty of curios: Henry Dixon and Alfred and John Bool’s photographic protests at London’s vanishing old buildings taken throughout the 1870s and 80s; James Boswell’s pre-Second World War sketches imagining London landmarks in the grip of an unspecified catastrophe, the lithographs resembling an early sci-fi comic; and the most fascinating of all, a ruin blueprint John Soane commissioned for the Bank of England when his designs were finally realised in 1830. Soane’s fanciful belief that he could control what time did to his masterpiece is no small part of the attraction. In Joseph Gandy’s vision of the bank’s future, its neat ruins sit precariously on a cliff top, a shard of light illuminating Soane’s handiwork. The start of the show certainly basks in Romantic depictions of moon-lit abbeys, but they soon give way to bunkers, estates, slag heaps and more ambiguous interpretations of ruins. That ruin lust is something of a luxury is made explicit by a room about war, and in particular by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s chilling close-ups of the faded walls of the former headquarters of the Ba’ath party in Iraq. The desperate mark-making by Kurdish prisoners is all the more uncomfortable seen just after numerous examples of aesthetically-prized disaster. London is shown throughout to be the subject of many a ruinous desire and such a specificity is one of the exhibition’s strengths. Looking at Jon Savage’s photographic catalogue of empty London sites started in 1977, there’s a sense of promise in these little-used desolate places, a punk sensibility familiar from the forgotten London edgelands of Derek Jarman’s films. But as Rachel Whiteread’s images of Clapton Park Estate mid detonation remind us, this exhibition takes place in a city where an all-devouring property market reigns and ruins are nowadays few and far between. (Battersea Power Station, not long ago central London’s largest ruin, sits across the river to Tate Britain now covered in cranes.) One of the last, and most timely works on display is Keith Coventry’s abstracted map of Elephant and Castle’s Heygate Estate. Even back in 1991, it mourned lost and failed utopian thinking and architecture. However 20 years ago the estate was still in use. Now it’s a ruin with a short life expectancy and Coventry’s painting resonates even more.

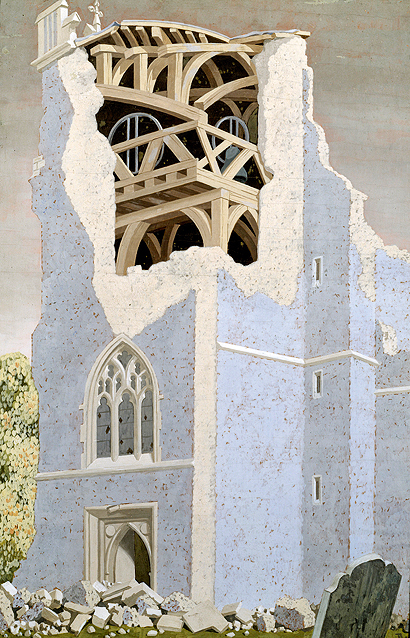

Coggeshall Church, Essex, John Armstrong, 1940 |

Words Isabel Stevens Ruin Lust, Tate Britain |

|

|

||