|

|

||

|

For her new book, artist Jessie Brennan spent time with the residents of the Smithsons’ brutalist estate to explore the human impact of the political battle over its regeneration. Here, she discusses her experience “I felt emotional,” admitted Abdul Kalam, former resident of Robin Hood Gardens who collaborated with me for my project on the Smithsons’ soon-to-be-demolished brutalist social housing estate in Poplar, in November last year. “I could’ve emailed, I know. But, you know what, I wanted to call you.” Kalam had just looked through a copy of our book: Regeneration! Conversations, Drawings, Archives & Photographs from Robin Hood Gardens. In his mind, the blocks were already consigned to history. For him, this book is a document that challenges the narrative told by property developers and politicians of the need for demolition and regeneration, but it is also a painful reminder of the bureaucratic processes that have brought Robin Hood Gardens to its knees.

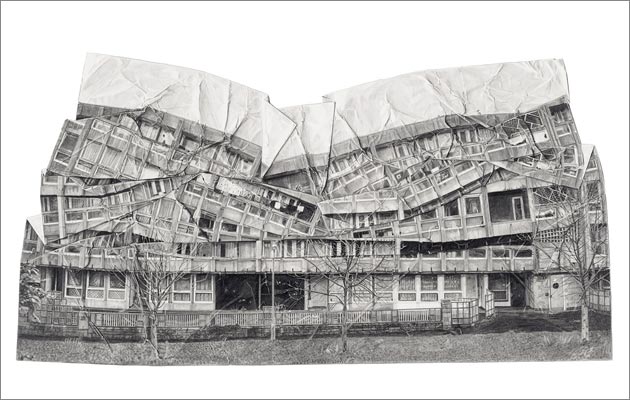

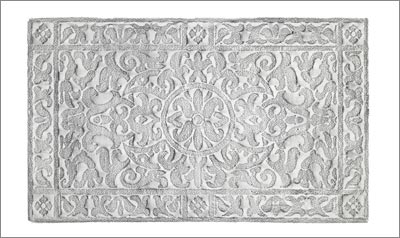

Conversation Pieces (no 34), 2014 Most readers will be familiar with the history of the Smithsons’ only realised public housing estate and, indeed, its current status – that a review of its listing was declined, making demolition almost a certainty – but fewer will know the impact the redevelopment is having on its residents. Known as concrete monstrosities or masterpieces by critics and supporters respectively, the buildings – and their apparent architectural successes and social failures – are debated and argued over, but the residents’ feelings are often either ignored or misrepresented. When I invited residents to explore with me their experiences of lived-in brutalism, it did not begin as planned. A printed photograph of the west block (my poster invitation placed around the estate) was quickly torn, shredded and crumpled. The image visualised the planned demolition of the building in poignantly prophetic detail, and the initial start to the project appeared an utter failure, crudely summarised: a screwed up poster; an unattended launch. Apparently nobody cares. |

Words Jessie Brennan

Above: A Fall of Ordinariness and Light (The Enabling Power), 2014

Images: Jessie Brennan, Abdul Kalam, Sandra Lousada, Smithson family archive, Tower Hamlets Local History Archives |

|

|

||

|

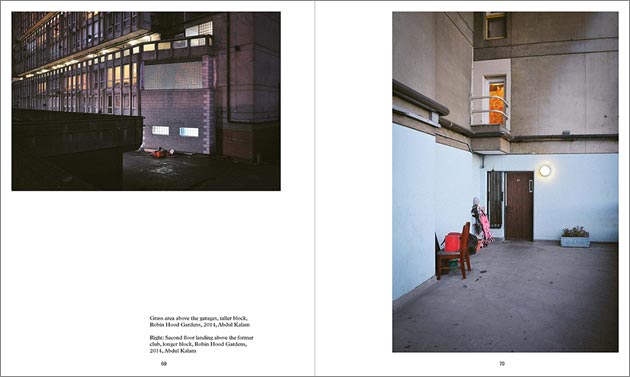

Photographs of Robin Hood gardens by Abdul Kalam (2014) featured in Brennan’s Regeneration! |

||

|

Of course, it’s nonsense to believe that residents do not care about the regeneration of Robin Hood Gardens – they deeply do, and they question whom it’s all really for. For instance, Sadia Aziza Islam, a 13-year-old who became homeless with her parents before moving temporarily to the estate last year, has noticed: “It’s like they’re driving us away to replace us with more wealthy people.” Abdul, who told me how he felt about the council-led demolition, agreed: “When boys sit down, or when mates sit down, what we say is, ‘they are basically driving the poor people out’. That’s what they’re doing. In the most simple of forms. It’s not racism – it’s more about wealth. ‘We don’t want you here ’cause you don’t belong here any more’. If we had a deep conversation, that’s what we’d settle on. That’s exactly what’s happened.” What potent politics these buildings contain. Thus, a radically different approach to engagement (socially, conceptually, critically, spatially) was required for the project, and it came in the form of conversations – developed out of the process of making doormat rubbings. |

||

|

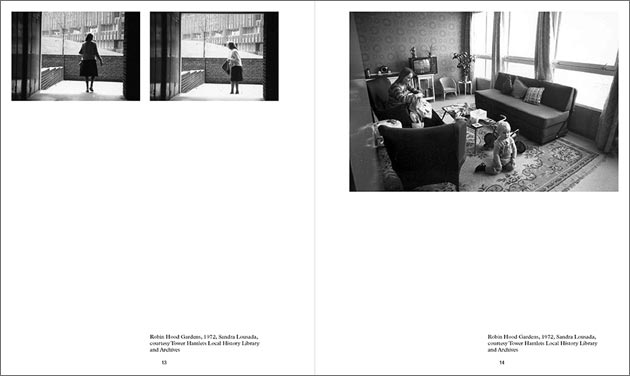

Residents of Robin Hood Gardens photographed in 1972 by Sandra Lousada |

||

|

The drawings, entitled Conversation Pieces, visualise a literal and metaphorical threshold between semi-public and private spaces, from the street deck to a home’s interior. They reflect the apparently unlikely human qualities associated with brutalism and the representational struggles the estate and architecture has occasioned. Another artwork, A Fall of Ordinariness and Light, commissioned for Progress by the Foundling Museum, responds directly to the problems associated with Robin Hood Gardens’ representation. It takes the form of a series of four graphite drawings that imagine the estate’s planned demolition. In the meticulously rendered drawings, the building appears to be in stages of increasing collapse and the story is one of social failure – the fall of post-war aspirations of progress, the end of architecture for social good. Nicholas Ruddock, resident of Robin Hood Gardens since 1982, rejected the notion of the estate’s apparent failure, however, when he explained what it was like to live in a brutalist building. “Don’t forget,” he said, “what the outsider sees is a harsh brutal concrete exterior, now dirty grey, when originally the concrete had a more golden hue or tone, as when first cast. However, as occupants we are looking out – secure in our citadel, overseeing the locality, as occupants of a castle might have in the medieval period. I always hoped the council – originally the Greater London Council – would get the exterior painted white, and this may have altered perspectives, attitudes, of outsiders to the monolithic block, which they saw as a delinquent among other properties.” |

||

|

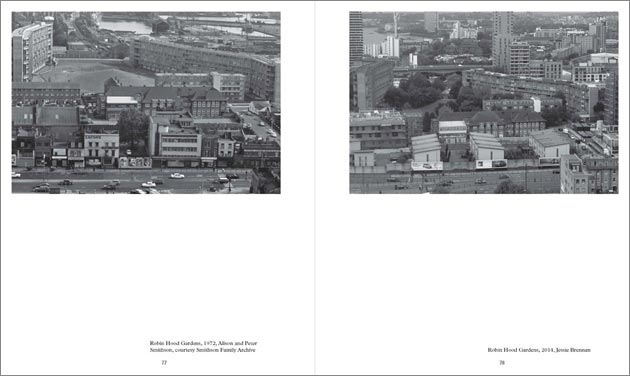

Robin Hood Gardens pictured in 1972 (left) and 2014 (right) in Regeneration! |

||

|

The slab blocks and brutalist architecture are not at all in themselves bad. “I keep on going back to it but the design was a wonder,” said Wayne Alison, caretaker of Robin Hood Gardens. But the management and maintenance offered by the local authority often was. This is not to entirely blame Tower Hamlets council either, which has endured decades of cuts from successive governments. However, in the absence of resistance to privatisation of public housing, the council endorsed the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens – and a reduction in proportion of social housing on the newly “regenerated” site – for short-term rewards, undermining its long-term capacity to provide decent, low-cost homes for low-income households. No wonder Robin Hood Gardens elicits such passionate responses from residents, evoked not only by the day-to-day experiences of life on the estate (plagued by broken lifts, a recurring lack of hot water or frequent blackouts) but also in how others – particularly the media – perceive and represent it. By inviting informal critique of the past in order to articulate experiences of the present, the project opens up critical space – inside homes and workspaces – in which the uncomfortable story of redevelopment is explored. The ideological attack on council homes, and the dismantling of public housing, is discussed at the level of individual lives. Through processes of drawing and dialogue, the politics of regeneration are made more human – revealing residents’ unquiet agency. |

||

|

||