|

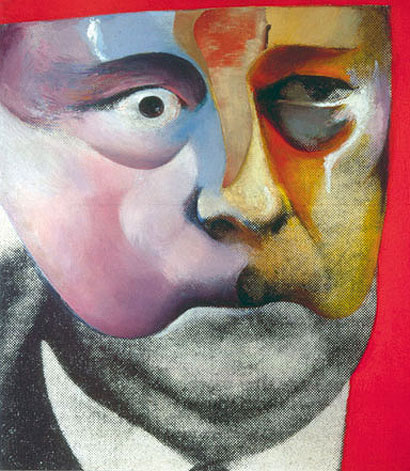

The Subject, 1988-90 (image: © Richard Hamilton) |

||

|

The godfather of British pop art feverishly mixes and remixes images until their meaning changes into something shockingly new. It still packs a punch, says Charles Holland There is a short film showing on the way into Richard Hamilton’s retrospective Modern Moral Matters at the Serpentine Gallery. It’s not, strictly speaking, part of the exhibition, but it provides a useful primer. One of Hamilton’s most famous works is Swingeing London 67 (f) (1968-69), a painting based on an iconic image of Mick Jagger and art dealer Robert Fraser’s 1960s drugs bust. TV news reports of the event have been subtly edited in the film so that Jagger’s clothing is described in an almost fetishistic level of detail. This is apposite because when I think of the incident it is Jagger’s lime green suit that I imagine first, largely as a result of Hamilton’s painting. This is how his pictures often work, repeating images over and over again until the mind starts to obsess on strange details. There are ten different versions of Swingeing London in the exhibition and, like proliferating conspiracy theories, each suggests an alternative version of events. Hamilton is an enigmatic but highly influential art-world figure. He not only coined the term Pop Art (in a 1957 letter to fellow Independent Group members Alison and Peter Smithson) but also, arguably, invented much of its basic repertoire of high art technique combined with pop cultural references. His most famous works, such as $he (1958-61) and Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956), were provocative collages merging car parts, consumer objects, human bodies and domestic interiors. The works in Modern Moral Matters, though, are explicitly political in nature. They cover his long career, ranging from the 1964 Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland to recent works depicting Tony Blair as a cowboy (Shock and Awe, 2007-08) and the Israeli political prisoner Mordechai Vanunu. Occupying the central space are a sequence of pictures concerning Northern Ireland, featuring portraits of British soldiers, hunger strikers and Orangemen. These are among Hamilton’s most powerful images. The Citizen, 1981-83 – a hunger striker stands in his cell draped in a blanket – evokes the heroic dignity of classical portraiture in an unlikely setting. Hamilton transforms the base image, evoking contradictory emotions, a precarious balancing act between reportage, commentary and iconography. All these pictures take media footage of actual events as their starting point, proceeding to blur, distort and recombine them until they become something eerily familiar and shockingly new. As the catalogue states, Hamilton’s work “interrogates the representations around us”. The power and complexity of the pictures – are they collages or paintings? Do they describe the events themselves or the way those events are mediated? – makes his more recent work all the more difficult to place. War Games (1991), for instance, is a painting of a TV on which an animated depiction of the first Gulf War is being shown. Below the TV is a rolled up newspaper, the headline on which reads: “The Mother of all Battles”. The TV appears to be dripping blood onto the shelves below. War, the painting suggests, is real, not an image or a headline on a newspaper. This is such a terrifyingly obvious point that I’m still left wondering if I missed something. Is Hamilton really being this straightforward? And what absolves this painting of the charge of superficiality levelled at TV or newspaper images? There’s something mischievous, surely, about a painting that urges us to cut through images to see the real thing? It is particularly ironic given that Hamilton’s previous work teaches us not to trust images, especially ones produced by artists.

Portrait of Hugh Gaiskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland, 1964 (detail) (image: © Richard Hamilton)

Shock and Awe, 2007-08 (image: © Richard Hamilton)

Treatment Room, 1983-84 (detail) (image: © Richard Hamilton) Richard Hamilton was at the Serpentine Gallery, London, 3 March – 25 April |

Words Charles Holland |

|

|

||