|

|

||

|

The long-promised era of robotics may finally be upon us – the Science Museum’s vivid retelling of its past and present allows us to consider the implications for our society and for our humanity, writes Debika Ray This may well be the start of the robot era. While Donald Trump and Britain’s Brexiteers promise their electorates a return to a golden age of secure, well-paid employment – if only they claim jobs and industry back from outsiders – machines with increasing dexterity, cognition, visual acuity, strength and speed are poised to replace workers in factories and shops, as well as their white-collar counterparts in offices. While we wait to see what work is left for us humans, it’s worth reflecting on how we got here. Handily, the Science Museum’s major exhibition for 2017 traces this 500-year journey, from early efforts to generate movement in autonomous objects to the latest walking, talking, dancing, singing robots that could soon become commonplace. The main focus is on humanoid robots, but some displays diverge from this theme, providing context and insight. Early clocks and astronomical models at the start, for example, set up the exhibition’s underlying premise: if we can animate lifeless objects, might humans themselves be nothing more than a combination of parts? Elsewhere, a mechanical loom from 1895 reminds us that this isn’t the first time we’ve feared human labour being replaced by machine.

Left to right: RoboThespian (2016), ASIMO (2000) and Kodomoroid (2014) Otherwise, the show largely narrates the development of robotics technology from the 16th century to the present day. It was mostly for spectacle at first: a bleeding Jesus and a clockwork monk that manipulated religious sentiments; 17th and 18th century automatons that mimicked living creatures, from spiders to swans; the famed ‘Mechanical Turk’, which travelled Europe in the late 18th century defeating allcomers at chess (controlled, of course, by a grandmaster hidden within). Meanwhile, anatomists were building replicas of human body parts, laying the groundwork for the humanoids that would follow. By the 20th century, robots had entered the popular imagination. Led by sci-fi writers and filmmakers, we began to imagine what they could be – compassionate and intelligent or perhaps amoral and dangerous. The reality was more prosaic: until the mid-century, robots were still essentially hollow, controlled from afar. Things started to change with the launch in Bristol of the Cybernetic Tortoise (1951), which could wander around and find its recharging hutch using its own sensors. After that, progress was rapid: technologists have replicated a complex range of human capabilities, from walking, running and handling objects to visual recognition, autonomous learning and non-verbal expression.

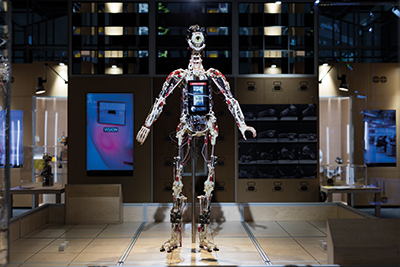

ROSA (France, 2010-16) was built to move like a human The final room is a menagerie of the latest humanoid robots for exhibition-goers to gawp at and interact with: from performers (actor ‘RoboThespian’ and trumpet-playing ‘Harry’) to functionaries (robo-receptionists, industrial workers and domestic carers) to show-offs (the ‘Kodomoroid’ looks almost human while little ‘Pepper’ dances and fist-bumps) to the truly horrifying (the Telenoid, an expressionless head on an armless torso, is intended to substitute for physical presence during a phonecall). The accompanying text invites us to consider questions about robots’ role in our future. Should employers pay taxes for robot labour? Does robot music have artistic value? Should you trust a robot to look after your parents or children? Would you be friends with a robot? Is it ethical for a robot to pretend to be human? A few minutes in their presence confirms that the last question isn’t one we need worry about yet. They are impressive but evidently still mere machines. The next stage – some version of consciousness – seems a distant prospect, and is largely unexplored in this show (granted, the topic is worthy of an exhibition of its own). It does feel like it’s still in our power to control the direction of this powerful technology – although the social and political forces that foist these androids upon us may be another matter. More hauntingly, it seems evident that this centuries-long iterative process of developing machines in our own image is a drive to understand what it means to be alive. Once we’ve created a robot that is indistinguishable from a human, can we really be sure what we are any more? |

Words Debika Ray

Above: The Animatronic Baby’s movements are programmed yet elicit an emotional response |

|