|

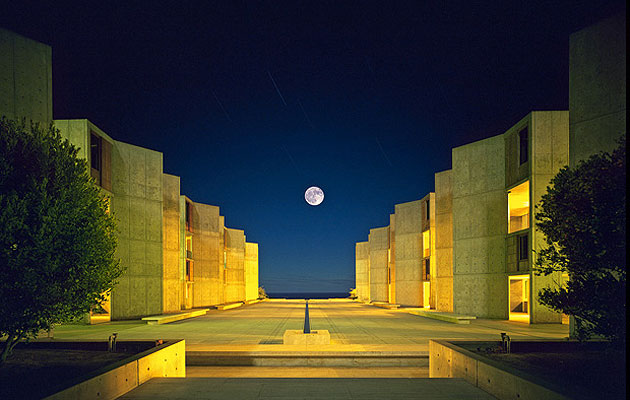

Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, 1959–65 (image: Raymond Meier; Salk Institute; Bart van Hoek) |

||

|

The first European retrospective of Kahn’s work in 40 years makes Owen Hatherley wonder about the architect’s place in the pantheon This exhibition on the Estonian-American modernist Louis Kahn has one explicit aim – to lift him to 20th-century architecture’s Mount Olympus, alongside Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. That it fails in this aim isn’t really a judgement on Kahn’s architecture as such – though I left unconvinced – but a judgement on the problems of architecture exhibitions. Sometimes models, plans and photos have to give way to some engagement with ideas or, even better, the lived reality of buildings. But in the grandly named The Power of Architecture we get too little of either. While the “big three” designed their most famous work for Berlin, Paris, Chicago or New York, Kahn’s masterpieces are largely either on Ivy League campuses, relatively obscure towns such as La Jolla or Fort Wayne, or in India and Bangladesh. It’s fair to assume that relatively few of Kahn’s European enthusiasts have actually experienced any of his major buildings. That’s not unusual in itself – Jim Stirling’s international rep was hardly affected by his finest building being in Leicester – but this lack of physicality passes into the presentation here. In the Netherlands Architecture Institute’s spacious béton brut rooms the chronological series of drawings, plans, wooden models, photographs and films has to do a lot of work.

The early stages of the exhibition concentrate on Kahn’s role as a New Deal radical in the 1930s and 1940s, engaging in the town planning of Philadelphia and co-writing popular tracts. This sense of an architect in the public sphere gradually dissipates, and we find Kahn morphing first into an experimental, Buckminster Fuller-aligned technocrat, and then an elemental brutalist-neoclassicist. The models here are sometimes beautiful, particularly that of Kahn and Anne Tyng’s City Tower for Philadelphia, a striking, unbuilt structuralist skyscraper, but the plans are the main attraction. One of the main exhibits is a Piranesi drawing that Kahn kept on the wall of his office, showing the plans of various structures in imperial Rome. These are echoed in the logo-like plans pinned next to the models, photographs and some fairly unremarkable drawings. They’re a clever touch, but the basically meaningless symbolism reinforces a sense of the religiose. Even more so do the quotes from the master lining the walls. “The sun never knew how great it was until it hit the side of a building.” “Structure, I believe, is the giver of light.” It’s the modernist’s Little Book of Calm.

So as the drawings and the ideas are of minor interest, we have to rely on models and photographs. They do indeed suggest Kahn was a great architect, but only suggest it. The giant volumes and austere materials of the buildings need to be experienced, and the exhibition obviously can’t provide a substitute. They could have circumvented this by posing problems about Kahn, about how his evocations of historic civic buildings brought monumentality and the past back into modern architecture, or about how the radical who had designed public housing estates and monuments to both FDR and Lenin became an apostle of the unchanging eternal virtues of architecture. Some of this is tackled in the catalogue, but the exhibition itself relies too much on the aura of the Great Man, assuming we’re already convinced of this greatness. In their keenness to add Kahn to the Mies/Corb/FLW pantheon, the curators also imply that if they were the revolution, Kahn was the architect who began the restoration, the reinjection of representational values; that he is the father of nearly every major post-1970 architect from Venturi to Zumthor; a maker of grand buildings whose long-demolished housing projects are best forgotten about. Or perhaps Kahn was just a very good modern architect – but looking at another plan and another slideshow, the mind does begin to wander. In the centre of the exhibition is a circular, enclosed and top-lit room housing Kahn’s watercolours, taken on a “grand tour” around Europe and Asia. They’re exceptionally pretty, often haunting, but they only reinforce an oppressive feeling of neoclassical virtue. It‘s as if to say “Look! He was training for his place in the canon!”

|

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||