|

|

||

|

Democratic, inclusive and grounded, Chicago’s inaugural architecture biennial distinguishes itself from its more established counterparts through its ambition to make a lasting contribution to the host city, says David Michon The inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial, the first of its kind in North America, opened to the public this Saturday. By all measures, it is set to be a huge success – with an expected 200,000+ visitors over its three-month run. The vision of the city’s ambitious mayor, Rahm Emmanuel, the Biennial was borne by a cultural plan that hopes, in part, to galvanise Chicago as a leader in the field of architecture – and surely will. Co-artistic directors Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda invited more than 100 artists and architects, from more than 30 countries, to participate – avoiding along the way the potential peril of becoming simply a showcase of large global/corporate practices. Instead, the duo has provided a platform for big ideas rather than big brands. Grima, whose CV is, in general, no stranger to the word “biennial” (among other credits, he was co-curator of the first Istanbul Design Biennial), and Herda, the spirited and efficacious director of Chicago’s influential Graham Foundation, have hit the nail squarely on the head. The Chicago Architecture Biennial is, perhaps most importantly and uniquely, immensely accessible. It’s main venue, the Chicago Cultural Center, is not only a landmark building in and of itself, it’s also commonly referred to as “the city’s living room”¬. Heavily used by the public, visiting exhibitions and events, the biennial is the first to occupy the entire (quite large) facility, and is completely free to all. (As it should be.) The tone of its displays was likewise refreshingly democratic. Though Herda and Grima set out no official theme, one seems to have emerged: housing. From the transformation of social housing projects in Bordeaux, that have saved the buildings from demolition and their residents from displacement, to 1:1 scale prototypes for new housing models, many participants took on the challenge of redefining residential life, and how we build for it. Vo Trong Nghia Architects (Ho Chi Minh City) and Tatiana Bilbao S.C (Mexico City) presented two of those prototypes, both addressing how to build new, sustainable homes quickly and cheaply.

The Chicago Cultural Center is the Biennial’s main venue, and was originally the city’s main public library A few press visitors thought to compare Chicago with the Venice Biennale, universally feeling refreshed by the former: more digestible in scale, more connected with its host city, with exhibitors chosen based on the value of their ideas versus their success in nation-branding (Chicago has no “national pavilions” or national displays, for instance). Though Venice has chosen, next year, to exhibit real-world lessons and solutions through its theme of “Reporting from the front”, its very formal format – a paid-ticket international tour of best-foot-forward architectural displays stuffed onto a ritzy island city – could never hope to be as inclusive, and for-the-people as Chicago. In fact, the notion that the Chicago Architecture Biennial should make a long-lasting contribution to the city it calls home is clear through its Lake Front Kiosk competition. The city of Chicago already has more than 40 food, retail and recreational services kiosks along its Lake Michigan shoreline – but none are particularly compelling, architecturally speaking. The biennial will, with each edition, replace one of these kiosks through international competition (the winners take home the BP Prize, and its $100,000 honorarium). The first winner was Rhode Island-based Ultramoderne, who designed “Chicago Horizon” – a 17m x 17m pavilion, reminiscent of Mies van der Rohe, using cross-laminated timber. Also on the biennial programme was the opening of the Stony Island Arts Bank, and its inaugural exhibition by Carlo Bunga. The Arts Bank is the fifth and latest community project by artist-turned-activist Theaster Gates’s Rebuild Foundation, a culture-driven neighbourhood redevelopment organisation that operates in South Chicago – a poor, mostly black, part of the city. What’s key, really, is that the biennial acknowledges that truly impactful architecture (or in this case reuse of it) isn’t the sole property of a city’s rich neighbourhoods or rich citizens. Development can do good, not just look good – and in fact, the power of architecture is at its greatest when it works for the disadvantaged. At the Chicago Biennial, architecture isn’t art, it’s action – and that seems to be a guiding philosophy of its organisers. Long may that continue, and may others take note. The Chicago Architecture Biennial runs until 3 January 2016 |

Words David Michon

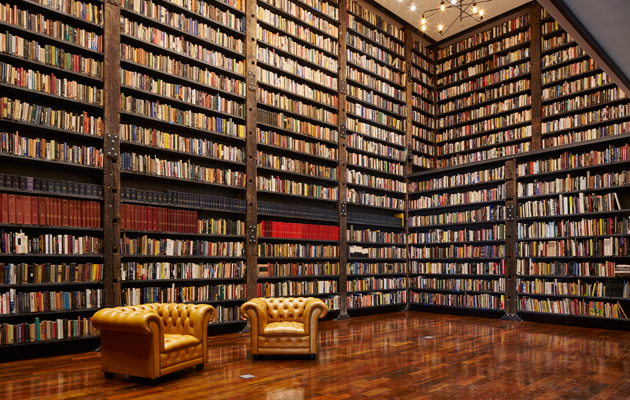

Above: The library of the Stony Island Arts Bank, a project by Theaster Gates. Its book collection was donated by the Johnson Publishing Company, the publishers of Ebony and Jet magazines

Images: Tom Harris, Steve Hall |

|

|

||

Tatiana Bilbao’s housing prototype attempts to create a model that is affordable but doesn’t sacrifice a comfortable layout or quality materials. Mexico is suffering from a major shortage of homes, needing about nine million more to accommodate is growing population