|

|

||

|

Architectural giants, developers and heritage bodies were left bloodied and battered by the battle of Mansion House Square. The RIBA does well to stay above the fray and let its fascinating exhibits tell the story, writes John Jervis If you don’t know about Mansion House Square, you’ve been living down a hole for the last few decades. Basically, a cluster of good Victorian offices at the heart of the City of London – most famously John Belcher’s Mappin & Webb building – were bought up by Peter Palumbo and his father from 1958 onwards. In 1962, the younger Palumbo commissioned a Seagram-esque tower from Mies van der Rohe, to be sited in a generous new civic square. Plans were finalised in 1969, gaining approval from the City Corporation on one condition: that work be completed in one phase. The final lease, on John Whichcord’s 1873 Bank of New Zealand, ran until 1986. After Mies’s death in 1970, battle raged for a quarter of a century as the fortunes of conservation waxed and those of modernism waned. Many of the threatened heritage structures were listed in the 1970s, and then encompassed within the Bank Conservation Area in 1981. Despite Palumbo’s strenuous efforts, his reapplication the following year was turned down; the scheme was finally rejected by the secretary of state in the wake of Prince Charles’s ‘glass stump’ jibe and the Guildhall public inquiry of 1984. Next up was James Stirling, commissioned by Palumbo just a year after appearing as a witness in defence of the Mies scheme. After another royal jibe, another public inquiry and continued heritage battles, the project – now bereft of the public square – was finally approved in 1989. Permission to demolish eight listed buildings was granted, leaving only the Bank of New Zealand standing. Despite further skirmishes with conservation bodies, clearance finally began in 1994. Stirling’s No 1 Poultry was completed in 1998, six years after his death. Last year it became the youngest listed building in the country, and here we now are.

Restored presentation model of Mies’s scheme (c.1980-85) Planning for this exhibition started two-and-a-half years ago, well before the listing process began. This coincidence is both a blessing and a curse. The above tale has an abiding interest as a foundational myth in British architectural history, passed down from one generation to the next. Of late, however, it has been plastered across the press as never before, with every critic and their dog embracing the chance to peacock on the subject – there was a risk that this exhibition would prove one oration too many. Fortunately, the show is an exercise in understatement, stripping the tale down to basics and letting the quality of the material, and the strength of the schemes, do the heavy lifting. A brief but telling display outlines the controversy, then the projects are tackled in detail, effectively separating the noise from the architecture. The former section reveals Denys Lasdun and Berthold Lubetkin’s support for Mies and Palumbo, but also includes a full frontal attack sent from Gavin Stamp to Margaret Thatcher (as well as a snide sideswipe from Mies’s old cohort Philip Johnson, in which he belittles the Mansion House scheme as ‘posthumous and unimportant’). Both projects could fill the available space many times over, thus the selection is necessarily precise and judicious. There is far more developmental material extant for Stirling than Mies, in part due to the latter’s preference for models over drawings. But these models are telling, alerting the viewer to subtle evolutions to the scheme after Mies’s visits to London in 1964 and 1967. And, in the case of two restored examples made for the 1984 inquiry, they are magnificent, from branded flags fluttering atop roofs of surrounding banks on the presentation model, to tiny croissants and wallets laid out in rows on the miniature counters of the model of the two-level shopping centre intended to sit below the square. Compelling replica drawing sets from 1967 and 1984 – the latter after prospective client Lloyds International had pulled out – can be browsed at leisure.

Top-down view of the presentation model prior to restoration The Stirling material is richer, though lacks the sad romance attached to lost projects. What it does have is exquisite execution, huge invention and manifold contextualism – the need to relate the project to surrounding buildings had been drummed into Palumbo by planners, politicians and City bigwigs by this point, and a return on decades of investment was becoming increasingly urgent. Exhaustive experiments with the geometries of plan, form, elevation, circulation and more (including alternative options for the tower and roof garden) led to detailed drawings for ‘Scheme A’, in which the Mappin & Webb building was left intact, and the final ‘Scheme B’, which used the entire site. The quantity of this preparatory material can only be hinted at, but its quality and breadth is made emphatically clear. In sum, there is much for Mies and Stirling fetishists to rub up against, with little associated hyperbole. Understandably, given constraints of space, wider contexts are left to one side. I for one would have liked my own particular fetish – the evolution of planning in the City – rubbed a little more thoroughly. Four intriguing drawings and a letter hint at the desperate desire of William Holford – associate architect on the Mansion House scheme – to be more intimately involved, given his longstanding role in London’s postwar planning, from Paternoster Square to Piccadilly Circus, and his ambition to oversee a radical rethinking of the City. Such interventions were met by Mies with ill-concealed disdain.

No 1 Poultry by James Stirling, Michael Wilford & Associates, viewed from Bank junction Another sacrifice is perhaps more important, and certainly more predictable. There is no real sense of the buildings destroyed (save eight miserable black-and-white photos taken by Stirling’s office of the crumbling Mappin & Webb building before its demolition), nor why people felt so moved to defend these structures, bar a couple of pamphlets to demonstrate the ‘emotive public stance’ taken by heritage groups. When a few nameless Victorian buildings, dismissed by Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and others as mediocre, are placed alongside dramatic, dynamic models and drawings from two of the greatest 20th-century architects, these protests inevitably seem ridiculous – the unthinking conservatism of a bunch of reactionary philistines. In 1983, SAVE published a sobering photographic record of the hundreds of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian buildings – pubs, warehouses, banks, railway stations, shops, houses – that had been torn down in the City during the postwar period, around half its remaining historic fabric. The battle of Mansion House Square was symbolic as much as specific. It nearly drove SAVE to bankruptcy, but it had to be fought. The City seemed intent on wiping away its past – its buildings, streets and plan – and London’s past with it. It may have appeared an exercise in futility, particularly as the demolitions continue to this day, but it is highly likely that No 1 Poultry would not now be listed if the City had not been forced into some form of accommodation with its built heritage. And it should also be noted that John Whichcord and his 19th-century peers did as much to create the modern City of London as anyone. Exciting as it is to continually satisfy our postwar cravings, perhaps they might one day get an exhibition of their own. Whichcord was, after all, president of the RIBA.

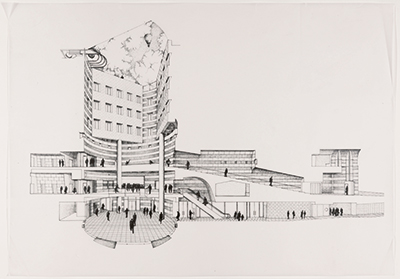

Sectional elevation of Scheme B for No 1 Poultry by James Stirling, Michael Wilford & Associates (1988, revised 1994) |

Words John Jervis |

|

|

||