The modernist bastion of the Met Breuer is breached by an exuberant celebration of the Memphis Group leader. But there are inherent dangers in trying to get beneath Sottsass’s surface, finds Noelle Bodick

About halfway through Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical, some time before plunging into the playful avant-gardism of the Memphis Group, visitors encounter a 1981 photograph of the collective’s members crammed into a miniature boxing ring. Exuberant, disorderly, debonair, they look like children in a playpen more than fighters about to exchange muscly jabs – let alone like what they, in fact, are: renegade designers posing a major challenge to the modernist project. In the most general terms, this exhibition is about the older man in the right corner of the photograph – the Austrian-Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007), who sits slightly removed from the action, wearing cowboy whiskers and a stifled look of amusement.

Sottsass led this postmodern challenge, influencing those in the ring, as well as many outside of it, with his seven-decade obsession with surface: vivid colours, throbbing patterns, asymmetrical, polygonal geometries. Even a decade after his death, Sottsass’s assembled oeuvre mounts a bold refutation, most obviously of its immediate surroundings, the Met Breuer in New York. This brutalist beauty, acquired two years ago from the Whitney, is made of a rough-hewn concrete and a pyramidal cohesion of right angles, cutting a figure of rationality and refinement. Outside, a single Cyclops-like window stares down, as if the all-seeing eye of modernity itself.

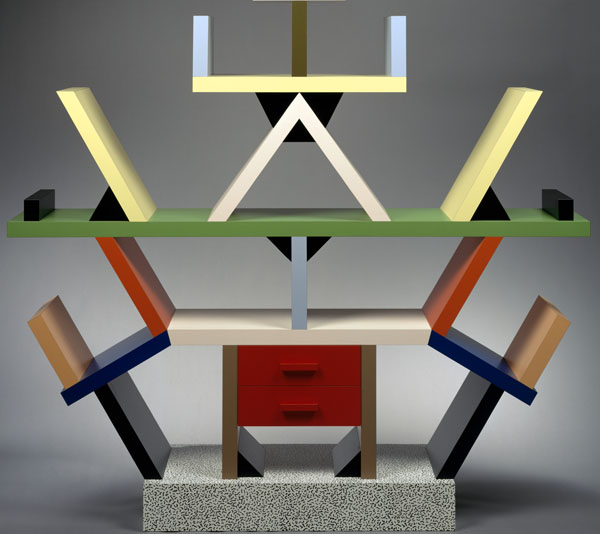

The Carlton Room Divider by Sottsass for Memphis Milano (1981)

© Studio Ettore Sottsass SRL

‘Functionalism, functionalism, functionalism,’ Sottsass once described modernism’s rigorous logic, eagerly adopted by American corporations and institutions, including the Whitney, in the postwar era. But, as postmodernists such as Sottsass told it, function’s primacy was outdated dogma; it precluded the flourish of ironical whimsy, orgy of colour, dash of innocent mania, or unexpected meeting of high and low that his design conceits frequently exploited. When set against the restrained backdrop of the Breuer building, Sottsass’s ice-cream-soda philosophy invites the question: do postmodernists just have more fun? The sympathies of the show’s curator Christian Larsen seem to cheerfully assent. This is an exhibition that sticks its tongue out at any pretentions of self-seriousness and any lingering modernist malaise, finding the catch-all of stylistic choices wholly stimulating. But it also offers more than the mere prospect of polychromatic cheekiness. Sottsass founded the Memphis Group in 1981, the same year Ronald Reagan was elected, marking the unexpected triumph of the right in the United States and much of the West, as well as the rise of consumer society and Schumpeterian market forces. How could industrial designers outfox the impersonality and multiplying homogeneity of this increasingly rampant consumerism?

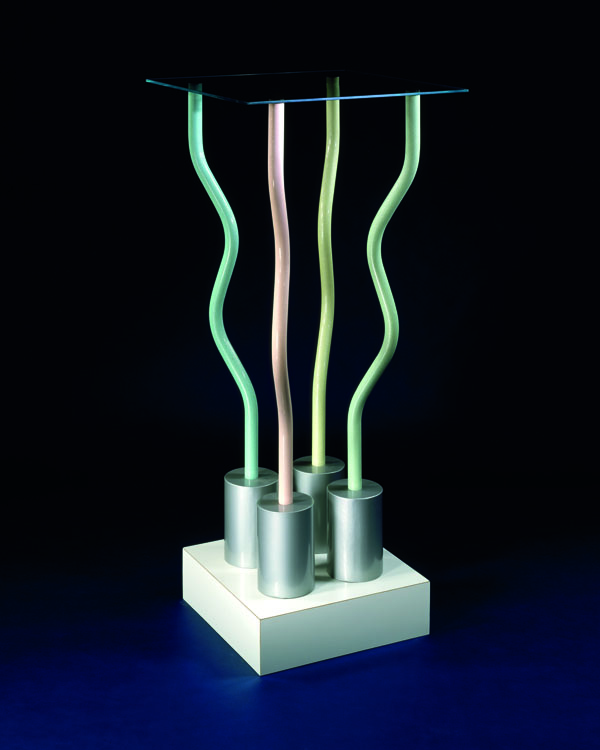

Sottsass spent in total seven decades, both before and after the Reagan era, answering this question. In his early postwar career, he worked for three months in the New York office of industrial designer George Nelson, before becoming design consultant for Adriano Olivetti’s famed machine and electronic corporation in Turin. He vigorously rejected the famous fire-truck red Valentine typewriter that he designed at Olivetti in 1968, fearing that ‘fucking red machine’ would forever eclipse all his more experimental work. Indeed, travels to India in the early 1960s had opened Sottsass to the ritualistic value of objects, which he then invested in his smooth ceramic totem poles, glazed offering plates, and chunky gold and quartz jewellery designs. Pilfering historical sources became not so much a crime of unoriginality as a strategy of supreme invention – a principle that guided the Memphis Group he founded in 1981. That year, the group turned heads at the Milan Furniture Fair, and for the next few years, with its obvious breaches of good taste. A simple fruit bowl tops the tall, reflective, zigzag columns of Sottsass’s Murmansk; his Ivory table ironically hosts a confetti of colour; while Andrea Branzi’s otherwise elegant glass-and-metal bookshelf in the shape of a boat sail is topped with cheapo-plastic Babylonian palm fronds. ‘Memphis’ was a Dylan reference, but its namesake cities – one in Tennessee, where Elvis Presley was born, and another in ancient Egypt – said it all. If its prices precluded most buyers – evidence of 1980s profligacy in the eyes of critics – Memphis at least made aesthetic concessions to lowbrow.

Now, the trouble starts when the show’s curator himself begins to forage repeatedly in the Met’s outsized collection to locate the historical sources of these many works, as well as future designs that Sottsass’s idiosyncratic style would, in time, inflect. Yes, there are a number of treasures – most notably, an Egyptian shabtis box to store mummies’ possessions in the afterlife, one of which Sottsass may have seen in Turin’s Museo Egizio as a boy, possibly inspiring his totemic Superbox, a single cabinet designed to contain all of one’s possessions in this life. But the ancient art often demands more studied attention from the viewer than Sottsass’s own, while the additional scattering of contemporary work dilutes the experience further, and with little justification – Thomas Struth, Frank Stella and Roy Lichtenstein have only tenuous connections to Sottsass.

Sottsass’s Structures Tremble table for Studio Alchimia (1979)

© Studio Ettore Sottsass SRL

Here we might reach the limits of a history told with a postmodern bent, even one as joyfully, if loosely, wrought as in this exhibition. The ambiguous language of the wall texts (compounded by the unfortunate lack of catalogue) often fails to clarify these links – Sottsass ‘perhaps found a kindred spirit’; an artist ‘presages Sottsass’; another work ‘surely shared’ qualities with Sottsass; an object (somehow) ‘acknowledges the formal similarity’ to Sottsass. With connections so vague and often unsubstantiated, it seems nothing in the whole world of art and design is untouched by Sottsass’s hand. It could generate a kind of farcical parlour game: Sottsass prefigured Iranian miniature painting, Sottsass’s use of colour influenced Almodovar’s films. The malign liberties of postmodernism – the breaking down of style, disregard for coherent narrative, the treatment of surface – may not extend to the task of the art historian. Ironically, Sottsass, the chief protagonist of the exhibition, suffers from being treated by the very conceit of his own slap-dash artistry.

Article by Noelle Bodick