In his new book, US architect Sekou Cooke redefines the way we think about both hip-hop and architecture – and shapes a manifesto for marginalised voices

Portrait of the author. Image: Michael Barletta

Portrait of the author. Image: Michael Barletta

Words by Sekou Cooke

The ‘double-consciousness’ required for being Black and an architect at the same time intensifies the calculus of success in America – an existence based on promises of prosperity rather than oppression, exclusion, and otherness. This desire to succeed echoes WEB Du Bois’ 1903 description of the African American: ‘He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.’

My expanded definition aside, only about 2% of all registered architects in this country identify as Black. This is a statistic that has only slightly increased from the 1% figure at the time of Whitney Young’s famously exhorting keynote address to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1968. ‘One need only take a casual look at this audience,’ he observed, ‘to see that we have a long way to go in this field of integration of the architects.’

Though precise numbers are difficult to source in a single location, the percentages of self-identified Black architecture students is only slightly higher, making architecture one of the most underrepresented professions of our time. This is unsurprising given the historical nature of architecture institutions catering primarily to White males, and the profession being established as a vocation for elites. Further, the discipline of architecture has promoted what architectural theorist Joseph Godlewski terms ‘shared vocabulary, history, references, techniques, practices, and codes of conduct’ from a position of Western idealism.

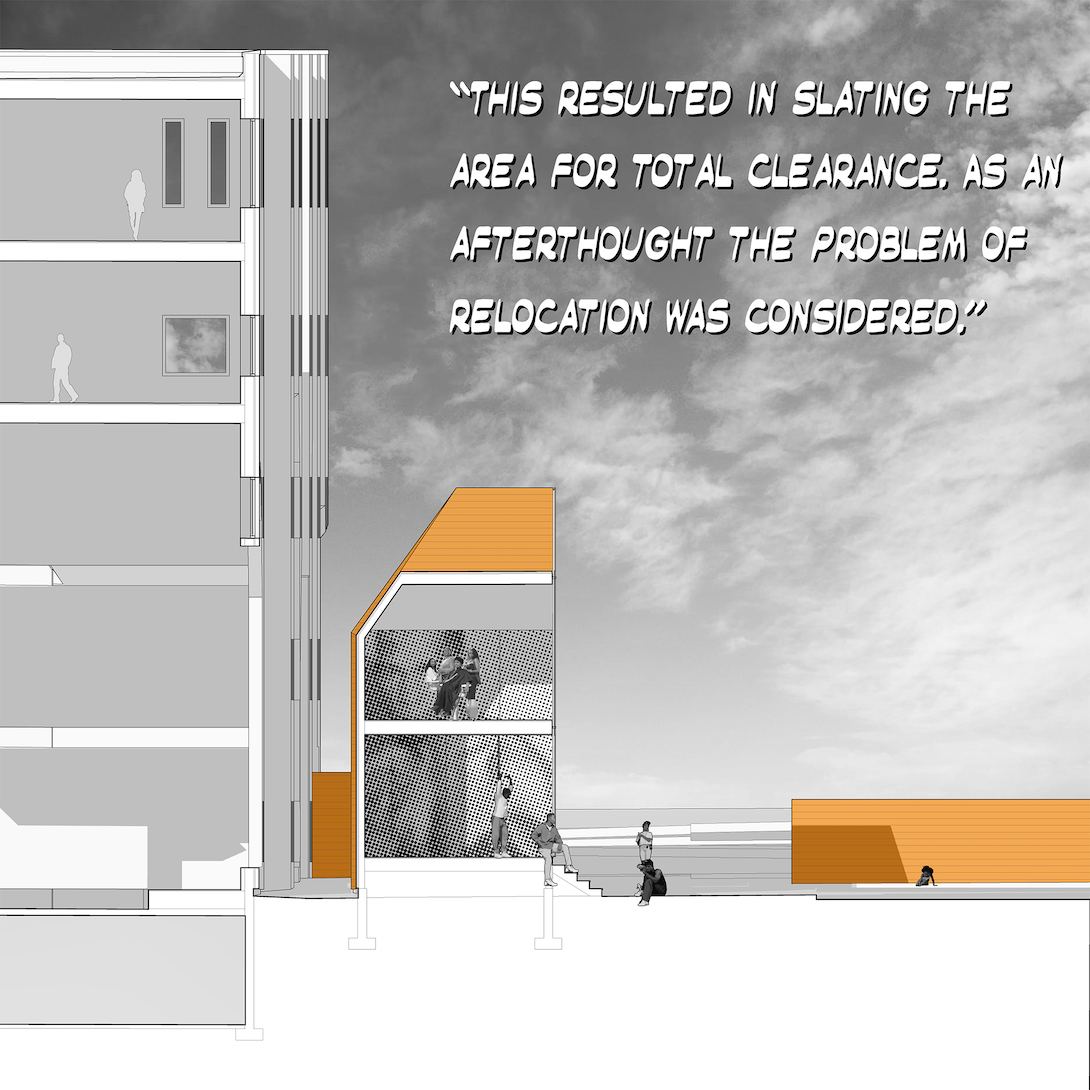

We Outchea: Hip-Hop Fabrications and Public Space (2020) by Sekou Cooke. Image: Courtesy of the artist & The Museum of Modern Art, New York

We Outchea: Hip-Hop Fabrications and Public Space (2020) by Sekou Cooke. Image: Courtesy of the artist & The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Many have managed to exist simultaneously as successful architects and Black. Few have managed to express their Blackness through their architecture. Within hip-hop culture lies the blueprint for an architecture that is authentically Black with the power to upend the racist structures within the architectural establishment and ignite a new paradigm of creative production.

Black people in the United States have been engaged in a century-long struggle for acknowledgement and relevance within architectural practice. Our ranks include several competent and highly accomplished individuals who have found remarkable levels of success within an overwhelmingly White profession.

Those who have succeeded, like Hilyard Robinson and Paul Revere Williams, though ‘Ignored by the architectural elites for [most] of their careers’ (according to architect and scholar Mabel O Wilson), have based their designs and processes on an assimilated Western norm. Others fully accepted within the starchitect category don’t fully identify as African American, like Ricardo Scofidio of Diller Scofidio + Renfro who, O Wilson notes, ‘is African American in heritage but does not identify as African American,’ and David Adjaye who identifies as British-Ghanaian.

The promise of Hip-Hop Architecture is in its ability to establish a way of working that is recognizably Black beyond mere aesthetics – an architectural practice, profession, and discipline deeply connected to the legacy of displaced African peoples in the Americas and legible in its production process and spatial resonance.

Sekou Cooke is an architect, researcher, educator and curator based in Syracuse, NY. This excerpt was taken from his book Hip-Hop Architecture, published in the UK by Bloomsbury

This article was featured in ICON’s Summer 2021 issue. Read the digital edition for free