|

|

||

|

The mood was set nicely. The busker in the subway that connects South Kensington underground station to the V&A was playing Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up. There it was, the pineapple in 1987’s cultural fruit bowl. Maybe the V&A had planned it that way. The chance for a bit of 1980s revivalism will surely be a draw for the V&A’s autumn blockbuster, Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990. But what about the design? Postmodernism is the finale of the V&A’s epic 12-year dissection of the design and architecture of the 20th century. The modernist line has been traced from art nouveau – 2008’s excellent Cold War Modern was its plenipotent, paranoid peak. Now, for the modern dämmerung. We begin with the end, which is – what else? – the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing development in St Louis on 16 March 1972. A cliché – but is it an unthinking or a thinking cliché? This being postmodernism, we can’t really be sure – this was the time of the knowing look back and the sifting and recycling of what had gone before. A generous side-gallery devoted to Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown is the only sunlight in an architecture section cluttered with ruins. A collage by Nils-Ole Lund presents James Stirling’s Engineering Building in Leicester as a wreck; Gaetano Pesce’s bunker-like Church of Solitude is carved out of a Manhattan sprinkled with Piranesian debris; Giulio Paolini arranges two classical busts so they appear to be considering the fate of a third, smashed on the ground. It’s a melancholy overture and, against it, Charles Moore’s Piazza Italia and Charles Jencks’ Garagia Rotunda seem morbid rather than jaunty. Over all this is Vangelis’ score for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, with the skyline of post-human Los Angeles looping on a big screen over Peter Shire and Ron Arad’s cargo cult garbage fetishism. The repeated use of Blade Runner is a nice touch – it has aged far better than most of the design, so much of which was a challenge to the eyes to begin with and has not improved with time. The only artefacts that land a punch past 1990 are from Memphis Group – its heroic Mesoamerican shelving units tower over the various bits of pastel tat and jokey shapery with a heroic but doomed air. Modernist functionalism may have been a kind of tyranny, and the desire to smash it up can be understood. But we are left with little in its place – only the tools of destruction and a bunch of punchlines. We are left with Ron Arad as the end of history, God help us. More Blade Runner heralds the fashion, and with it music and graphic design, which plough into one another in the 1980s with the rise of the music video and style magazines such as The Face. Image triumphs over substance, and the cement mixture of nostalgia and revival that comprises much of pop culture today is set in motion. Still, the lasting freshness of this experimentation – driven by advances in video and publishing technology – is an immense relief after the preceding bric-a-brac. At this point, as the exhibition’s narrative has it, postmodernism “sells out”, goes corporate – not exactly the most surprising development. Philip Johnson puts a Chippendale summit on the AT&T building, Michael Graves designs a Mickey Mouse tea set. Between Alessi, Starck and Notkin, the framework of much of today’s design can be glimpsed. Postmodernism: Style and Subversion could have done with a little more depth and a little less breadth, although its restless movement from one topic to another could be seen as thoroughly in-theme. It is, overall, a well-made show that struggles with its protean and difficult subject matter. If some of it is crass, it is only because the material is crass. And there is some salutary value in gazing at the lowest points – we can treat the show as Postmodernism: A Warning From History, and look back to learn and avoid, rather than recycle and celebrate. Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Until 15 January 2012

|

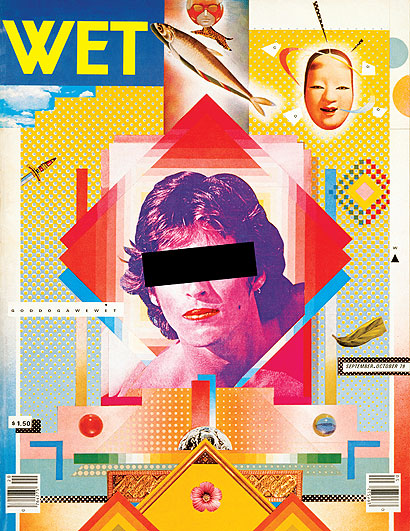

Image April Greiman, Jayme Odgers

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||