|

Frank Lloyd Wright Jr’s Metropolis-like LA civic centre (image: Architecture and Design Museum, Los Angeles) |

||

|

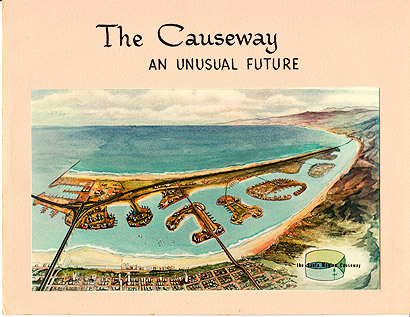

How might Los Angeles, the celluloid city, have been an urban utopia, asks Christopher Turner More than 50 unrealised projects are collected in the A+D Museum’s smart, entertaining show, Never Built Los Angeles. Similar exhibitions of urban nostalgia are currently on view in Chicago and San Francisco, but there is something about LA that lends itself particularly well to such an exercise in alternative history. Hollywood has always been adept at romanticising and glossing its home turf, overlooking the shabby sprawl by overlaying it with Blade Runner-like dreamscapes. Curated by architectural journalists Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, many of the architectural ghosts on view here resemble film sets, shimmering additions to a virtual, celluloid skyline. LA, with its striking ocean and hill setting, has always been characterised by innovative domestic houses, an eclectic frenzy in which Venetian villas sit next to haciendas, Swiss chalets next to Japanese temples. The émigré Austrians Rudolph Schindler (who came to the US in 1914 to work for Frank Lloyd Wright) and Richard Neutra (who joined him a decade later, living for a while in Schindler’s Kings Road House, an early LA experiment in communal living) brought to the Californian home a new and distinctive architectural rigour. The influential Case Study Houses continued their modernist project, as did John Lautner in the hilltop retreats that Hollywood often co opts as villains’ lairs. However, as Thom Mayne argues in a foreword to the accompanying catalogue, public architecture in the city has always lacked the institutional framework that traditionally supported civic projects in other American cities, such as Chicago and New York. With the rare exception of places such as the Walt Disney Concert Hall and Griffith Park, LA’s city planning has been an uninspired, lacklustre affair dependent on private money and compromised by personal agendas. The city, home to Pritzker winners Mayne and Frank Gehry, many of whose aborted schemes are on show, has largely been an exporter of home-grown talent. The exhibition shows that this has not been for lack of idealism or architectural imagination: LA might easily have been a very different place. In 1930, for example, the Olmsted brothers proposed a necklace of inter-connected “pleasureway parks” meandering through the city; in 1925 Frank Lloyd Wright’s son mapped out a civic centre to rival Washington’s, with underground speedways and rooftop landing strips; that same year Kelker and DeLeuw suggested a radical transportation scheme, including hundreds of miles of subway and monorail tracks, as a solution to LA’s infamous congestion. But the city never seemed to have the will, or the budget, to realise these ambitious proposals. There was no wily, empowered politician like Robert Moses to bulldoze them through. Neighbourhood campaigners in New York finally succeeded in halting Moses’s relentless and brutish bridge and tunnelling, and this exhibition also includes schemes that are clearly bullets dodged. A 1965 idea to turn the coastline between Santa Monica and Malibu into a massive freeway, building into the ocean a Dubai-like network of linked islands, represented a greedy land-grab. In 1943, a 1,290ft Tower of Civilization was proposed as the centrepiece for the LA World’s Fair, a megalomaniacal, empty gesture that would have been higher than the Empire State. In 1989 Donald Trump tried to finance a monstrous, gilded, billion-dollar tower that would have been the world’s tallest skyscraper. The exhibition, a palimpsest of parallel realities, encourages you to ask the question, at once utopian and dystopian, “What if?” As I sat in traffic, musing on LA’s future, I found myself wondering whether Peter Zumthor’s expansion plans for the nearby Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an amoebic form that echoes the surrounding tar pits, will come to fruition or languish on the drawing board like past schemes by OMA and Steven Holl. It seemed unlikely that Elon Musk’s Hyperloop between LA and San Francisco (see Anatomy Of, page 19) would see the light of day. And it seemed depressingly possible, despite the numerous stillborn towers I had seen, that the unsightly two skyscraper complex in Hollywood, a development that will dwarf Capitol Records and has just been granted planning consent, would.

The proposed causeway between Santa Monica and Malibu (image: Architecture and Design Museum, Los Angeles) Never Built Los Angeles, Architecture and Design Museum, Los Angeles, Until 13 October Never Built Los Angeles by Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, Metropolis, $55 |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||