|

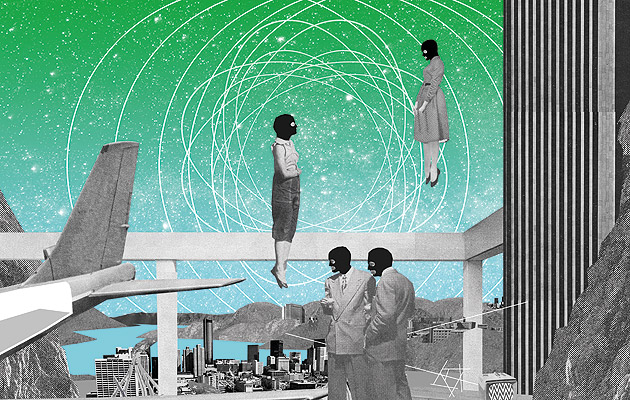

Installation image of Room 11, by Mario Wagner (image: Victoria and Albert Museum, London) |

||

|

Graphic designers and artists illustrate a fictional text off the page and in the museum. Hannah Gregory wanders around the story “Here is how to remember. First you must pick a place.” So begins Hari Kunzru’s Memory Palace, a fiction commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum as the foundation for an exhibition exploring the relationships between text and space, site and story. A memory palace is a mnemonic device, attributed to the ancient Greek lyric poet Simonides, that involves placing images of memories in physical locations. Kunzru’s Memory Palace takes place in a post-apocalyptic London, where the information infrastructure has been destroyed. The ruling party has banned books or any form of recording, so the tale’s protagonist takes to constructing short paragraphs about the plight of his group of renegade “memorialists”, who use mnemonics to retain fragments of their past. Imprisoned in a small cell, he assigns memories to its minor details, augmenting the restricted area through his imagination: “As I populated it with the things I was given to remember, the cell began to grow. It was like pushing the walls outwards with my hands.” The material book of Kunzru’s text, beautifully produced by Sara de Bondt studio, was given to 20 graphic designers and illustrators, who expanded it to inhabit the museum. The exhibition itself embodies a memory palace – an architecture of minimal turrets and partition walls in cream, conceived by the architect CJ Lim, with each artist’s interpretation ordered within. After the promise of “a central space containing the narrative spine” with “a series of rooms leading off this to reveal different memories”, I was expecting a more elaborate configuration to convey the chambers of the mind’s palace. The pared-back design is effective though, and the choice to guide the reader with a printed plan, rather than with labelling, is appropriate given the inclusion of extracts from the book; these fragments are represented in a clear but expressive typeface displayed next to each visual response. Artistic contributions range from object-based curiosities, illustrative storyboards and larger built structures, to more lateral interpretations; graphic artist Sam Winston’s embossed metal plates, for instance, which deconstruct the periodic elements of a gold watch, a paper book and a SIM card (representing the banned concepts of time, knowledge and technology). Kunzru says he came up with the theme of post-information apocalypse when he realised that “we have outsourced our memories”. In Memory Palace, “the internet” is the term for the memorising group, as depicted by Isabel Greenberg in images where letters are scattered between people, the remnants of London icons lingering in the background. The prisoner’s dystopia forbids lettering – which conversely invites contributions of typographic play, such as Tel Aviv-based Oded Ezer’s looped films, which dissect language through alphabet games to suggest alternative ways of “reading”. Presenting the exhibition as a reading experience seems an intellectual idea, yet the action of walking into a story is satisfyingly childlike. And the more garish objects – a multi-coloured jenga tower that reconstructs the tale’s definition of “museum”, by Berlin-based designer Henning Wagenbreth, and illustration collective Le Gun’s 3D chariot, pulled by urban foxes – may well be aimed at younger visitors. Memory Palace is a timely experiment in visual storytelling. We need immersive tales, the exhibition’s curators say, when the nature of reading is in flux – even though, as historian of the book Anthony Grafton writes in Codex in Crisis, text alone may pose a form of “spatially defined memory theatre”. The two-dimensional interpretations may be the most engaging, but the exhibition is committed to moving between media, and to placing storytelling inside the museum. While not all of these text-to-space or text-to-image translations succeed, many lead the visitor into the corridors of the mind.

Installation image of Room 11, by Mario Wagner (image: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011) |

Words Hannah Gregory |

|

|

||

|

Chariot-pulling fox in Ambulance, by Le Gun (image: Victoria and Albert Museum, London) Sky Arts Ignition: Memory Palace, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Until 12 October 2013 |

||