|

The objects hoarded by artists make for a dizzyingly stimulating show, says Christopher Turner, but they lose some of their magic away from the intimacy of the studio Artists are often the most prolific collectors, not only of each other’s work, which they swap and trade, but of ephemera. The shelves in their studios seem to be crammed with curiosities: reminders of the richness of the world outside, magical totems that serve as both decoration and inspiration. After Andy Warhol’s death, Sotheby’s auctioned off his collection. There were 10,000 lots, and the sale took ten days. The artist was a hoarder, and didn’t arrange his collection with any rigour. Indeed, the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh is still opening and cataloguing his time capsules, souvenirs that he would pack and store in dated boxes whenever the amount of stuff that he collected threatened to overwhelm him. One of the things that Warhol collected was toys, whose packaging he used in his silkscreens. In 1983, he exhibited 128 Toy Paintings, made especially for children. A few of them are shown at the Barbican exhibition, Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector, just as they were originally exhibited, on wallpaper depicting a shoal of fish, which sparkle against a blue background and all swim, mouths open like windsocks, in the same direction. Adults had to squat down to look at the canvases – a spaceship, a police car, a monkey, or a helicopter – which were hung at the eye level of five-year-old children.

A mid-19th-century montage display of 24 tropical birds, maker unknown, from Damien Hirst’s Murderme Collection The Barbican exhibition traces such influences through a range of very different artists. A work by each serves as a prism through which to look at the things they collect. Howard Hodgkin has an impressive range of Indian miniatures, which directly influence the rich palette that is splashed around his canvases and their frames like pigment at the Hindu festival of colours. One can see the convergences between Martin Parr’s photographs and his collection of postcards, exhibited here as multiples and treated with a wry wit (one series of monochrome “cities at night” is displayed together like Malevich’s black squares). For some artists, such as Jim Shaw, their collections are the artwork. Shaw collects thrift-store paintings, surrealistic and expressionistic outsider art that he treats with the reverence one would Jean Dubuffet. The curators have selected artists who ignite one’s curiosity; a visit is as dizzyingly stimulating as a trip to an oriental bazaar. For all the strained quirkiness, their collections can be crudely divided into two types: there is the faux Victoriana, arranged like cabinets of curiosities. Damien Hirst, for example, has loaned a collection of mutant taxidermy, exhibited in mahogany vitrines, as has Peter Blake. The potter Edmund de Waal presents his famous Japanese netsuke (including the hare with the amber eyes), as well as a collection of fossils and stones with similar museological reverence. Photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto collects optometrists’ equipment, including glass eyes and 17th-century treatises on optics.

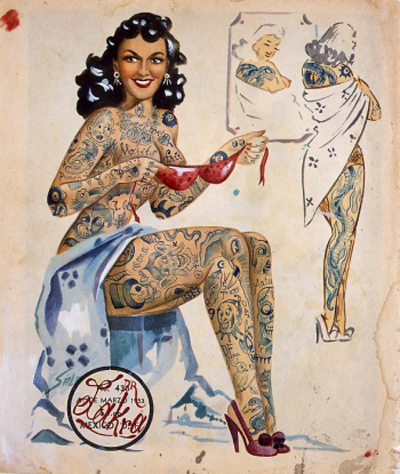

Dr Lakra, Frente al Espejo (The Mirror), 2003 – collection of Robert Devereux Then there is the ersatz. The Mexican tattoo artist, Dr Lakra, collects record covers featuring marked skin. Hanne Darboven has amassed a number of gaudy figurines and carnival relics. There are Sputnik space oddities (Parr again), Punch and Judy puppets (Blake), and a memorable lampstand made to resemble an overstuffed hamburger (Martin Wong). Warhol is obviously the patron saint of kitsch, and his collection of garish cookie jars is arranged in neat rows, as if it were an installation by Jeff Koons, the tidy presentation belying Warhol’s accumulative, obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Indeed, one of the strengths of Magnificent Obsessions is that every collection looks like an installation. They cohere as artworks in their own right. But this is also something of a weakness. One would like to see these artists’ objects in context, as working collections. One thinks of Henry Moore’s studio, with its shelves of pebbles, bones and flints that he picked up on country walks. Moore would work them with clay, creating miniature versions of his monumental forms. André Breton described his 1933 visit to Picasso’s workspace as an initiation into “the studio’s secrets of the boudoir”, and a tour of the Barbican exhibition left me longing for a flavour of such intimate access. Only Sol LeWitt’s contribution – a photographic index of 1,000 mundane things he amassed between 1980 and 2012 – presented here as an autobiography, hints at such a document. The exhibition ends on 25 May |

Words Christopher Turner

Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

Images: © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2014. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd; collection of Edmund de Waal. Photo by Justin Piperger; Martin Parr Collection/ Magnum Photos/ Rocket Gallery; Kate MacGarry, London; Movado Group |

|

|