|

|

||

|

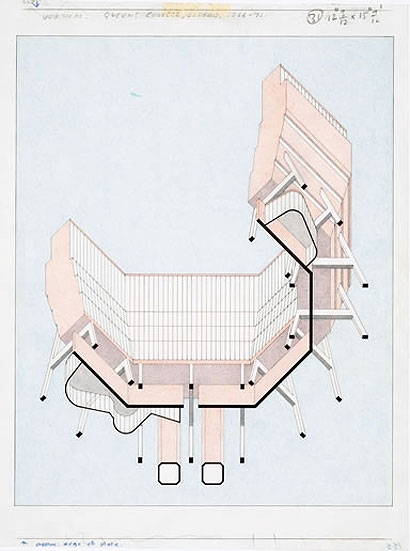

All architects use drawings, but few have done so with the power and conviction of James Stirling. His machine-like axonometrics and pristine perspectives are as famous as the buildings they depict. This exhibition of drawings and models from the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s archive is therefore highly pertinent to any attempt to understand Stirling’s controversial career. In recent years a kind of critical party line has emerged about Stirling that goes something like this: his early university buildings – at Leicester, Cambridge and Oxford – were brilliant but technically flawed. For a while, his star waned and he failed to win much work, at least in the UK. By the time he started building again in the 1980s he had unfortunately fallen under the spell of postmodernism. While his undeniably brilliant Staatsgalerie Stuttgart was almost universally praised, other buildings – including the extension to Tate Britain in which this exhibition is housed – were far less warmly received. This is a superficial reading, however, that relies on a narrow judgement of taste. Stirling’s career was actually one of impressive intellectual consistency. Arguably, he reached a peak of creativity during the 1970s with a series of brilliant unbuilt schemes that seemed to lead inevitably towards the triumph of the Staatsgalerie. While these projects began to incorporate explicitly historical imagery for the first time, they were also clearly developed from his earlier work. Although the layout of this undemonstrative, scholarly exhibition conforms to the tripartite view of Stirling’s career, curator Anthony Vidler’s intelligent, leading captions also emphasise the consistencies and continuities. Almost from the off, Stirling was a spatial collagist, designing powerful and compelling compositions formed from architectural fragments. His buildings are broken down into separate elements, spatial archetypes connected by elaborate pedestrian routes, ramps and walkways. Rotundas, stoas and squares appear over and over again, sometimes as spaces carved out of something solid, or as solid objects floating in space. Take the form of the basilica, which appears in the unbuilt Cologne Museum competition scheme as a sunken and miniaturised version of the nearby cathedral and later as a solid, vertical extrusion in the Science Centre building in Berlin. His conception of the building as a small city, and of the city itself as a mixture of figure and ground, solid and void was undoubtedly influenced by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter’s Collage City (published in 1978), but it was present in Stirling’s earliest work, too. It makes its most explicit appearance in perhaps the strangest drawing in this exhibition, a reworking of Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 Plan of Rome in which Stirling embedded a number of his own buildings. Stirling used drawings both as a formal tool and as a kind of propaganda. Sometimes they were even drawn after the building was completed, marking them out as emphatically cultural rather than technical acts. Some of the most famous images were drawn by employees in Stirling’s office who went on to become famous in their own right – including most notably Léon Krier – raising interesting questions about authorship and the cult of the “starchitect”. Stirling undoubtedly used drawing to cultivate his own mystique. Possibly, he also used it as a way to offset the technical problems associated with the completed buildings. The famous worm’s eye view of the Florey Building in Oxford (below), for instance, has an icy perfectionism, as if the building is an alien object beaming down to us from space. These drawings are also very beautiful, virtuoso displays of the disappearing art of hand draughtsmanship. Stirling remains a controversial and divisive figure. In the recent history of British architecture, however, there is no one like him. Like the buildings they describe, the drawings in this exhibition combine an audacious compositional bravado with a deep understanding of architecture as an intellectual act. James Stirling: Notes from the Archive is at Tate Britain, London until 21 August 2011

credit Canadian Centre for Architecture |

Image House for the Architect model

Words Charles Holland |

|

|

||