|

|

||

|

Darran Anderson’s ambitious tour of the city in myth, fiction and history veers down some unexpected paths, but Will Wiles is more than happy to tag along Some years ago, in this magazine, I made the observation that a book about lost buildings by a noted commentator on architecture had the odour of the desk drawer about it. Perhaps I should have said the glow of the bookmarks folder, just to be up to date, but the principle is the same. It was a rag-bag of oddities of the kind that architecture buffs accumulate over time – the disappeared Singer building in New York, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, Hitler’s unrealised plans for Berlin – yoked together in picture-book format and stuffed with padding. Interesting in places, but never sustaining that interest. Just sweeping up these odds and ends and putting them between hard covers is about as satisfying as a listless scroll through Tumblr. Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities contains many of the same fragments of architectural history, but is an altogether different beast. There are no pictures, for one thing. One or two might have been welcome, but it’s admirable that the publisher resisted the urge. This is a proper book. Anderson has taken a colossal theme – the idea of the city over the course of human civilisation – and, if anything, expanded its boundaries in an extraordinary feat of sustained argument and imagination.

It defies handy summation. Imaginary Cities roams freely, and with easy authority, from the first scratchings on a cave wall to last month’s architecture magazines. To give a sense of Anderson’s casual ambition, a chapter on “The Tower” (no small subject) finds time to throw in a potted history of nuclear obliteration and Godzilla movies. He moves with easy grace from Herodotus to Hugo Gernsback, a range of reference that enriches already enjoyable prose with inventive imagery. Take this discussion of the scenery found in medieval sacred art: The Annunciation gave rise to a variety of cloistered walled gardens (“Hortus Conclusus”) where Mary was kept from the corruption of the world; part prison, part sanctuary (an urban Locus amoenus). The archangel Gabriel would descend into her courtyard like a helicopter in a prison break … In Perugino’s depiction, Christ hands Saint Peter the keys to heaven in a cityscape that extends off into the distance like a marble Tron. Anderson wears his erudition very lightly, sometimes too lightly. Quote attribution is rough and ready in places, and there are repetitions and slips; in particular he has a capricious way with names. However, this reviewer saw an uncorrected proof and I am told that most, if not all, of these errors have been caught in the final version. Even if some have slipped the net, the reader will surely be moved to decisively overlook them, on the grounds that this is a hugely ambitious book for a small publisher, and Anderson is delightful company as an author. Coleridge’s vision of Xanadu is here, of course, and in a sense pervades the text. There’s a dreamlike quality to the non-linear, allusive way that Anderson drifts from subject to subject. That, and the immense breadth of material included, means that while Imaginary Cities is always a pleasure to read, it doesn’t always leave that deep an impression on the memory. But that, in a way, is the point. This is not just a study of cities in myth and fiction (although heaven knows that’s a big enough topic) but a study of cities in general; or rather, a study of the human imagination and the way that it interacts with the world. The epigraph comes, aptly, from Italo Calvino, and Imaginary Cities is an enterprise in the Invisible Cities vein – one that shows the city to be a protean, infinite, impossible subject, and that its most important infrastructure lies within the human skull. |

Words Will Wiles

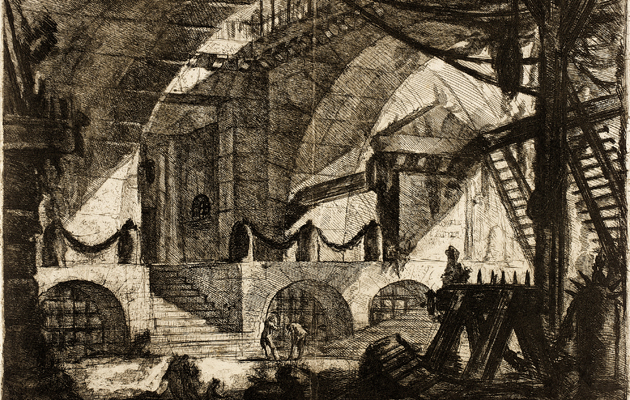

Above: Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s engraving The Sawhorse, from his series Carceri d’invenzione, c. 1749–50

Imaginary Cities |

|

|

||