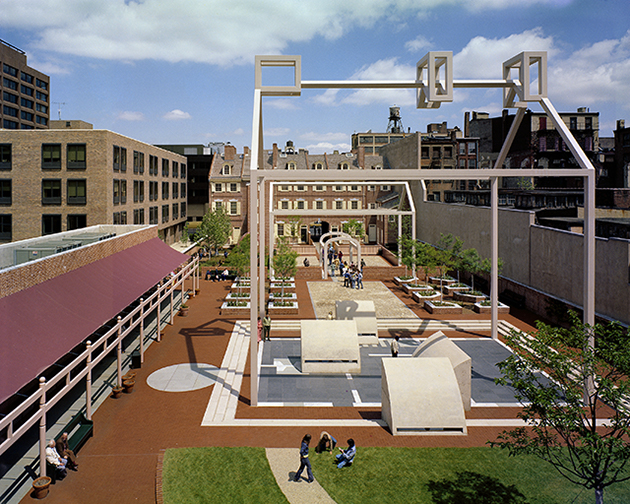

Franklin Court ‘Ghost Houses’, Central Philadelphia Photograph by Mark Cohn. Courtesy of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc.

Franklin Court ‘Ghost Houses’, Central Philadelphia Photograph by Mark Cohn. Courtesy of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc.

Robert Venturi’s Philadelphia ghost houses barely count as buildings, but in many ways they are the perfect epitaph for a man who transformed our architectural landscape, writes Edwin Heathcote

What better cipher could there be for an obituarial tribute than a ghost house? Robert Venturi, who died on 18 September, was renowned as a resolutely modern architect who used the tropes of historical architecture to create a new symbolic modernism, which toyed with preconceptions, with logic, with taste and with snobbery.

His architecture wanted it both ways. As Tom Wolfe wrote in From Bauhaus to Our House, Venturi managed to subvert architecture from the inside, using a series of codes that – often – only other architects would understand. Buildings like the Vanna Venturi House (built for his mother in 1962-64) used mannerist influences applied in paper-thin form to a pure modernist villa. There was something for everyone.

The first building by Venturi and Scott Brown I encountered in the flesh was one that was barely there at all. Three decades ago, I worked for a brief time in Philadelphia and, quite accidentally, came across Franklin Court. I wasn’t particularly interested in postmodernism at the time (though I did, of course, like Aldo Rossi) and I didn’t make much effort to search out its buildings. The style had become ubiquitous by then and we were all getting a little queasy with it. But this odd little intervention is a brilliant landmark and a strikingly original evocation of history and urban memory that isn’t quite a building. As such, it avoids the tics and tropes of postmodernism (and hence never quite went out of fashion – or came back in again) and remains as much of an architectural drawing as a realised structure.

Franklin Court was built in 1976, on America’s Bicentennial, and commemorates the approximate profile, scale and location of Benjamin Franklin’s house in Philadelphia’s Old City. The site which sits over the excavated remains of the actual house has been made into a public space and a park, a popular place not only for tired-looking tourists but also for office workers eating their sandwiches. And at its heart are two steel frames sketching the outline of the historic houses that defined the court in the 18th century. In form they are something like Monopoly houses, frames which speak of the essential houseness of the houses that are no longer there.

The first of them has an archway, which is of course absurd. You feel compelled to walk through the arch into the not-there-courtyard but you could just as easily walk through the walls, which aren’t there either. The second has chimneys, which just hang there, in the air, three blocky frames of different sizes suspended above you like minimalist sculptures.

Beneath the ghost houses are giant concrete cowls, which allow visitors to peer down into the basement and see the physical (and pretty unimpressive) remains of the floors and walls of the original house. These squat concrete structures are pure 1970s brutalism. They could be ventilation shafts for an underground car park or sculptural, self-conscious vents in a slightly Paul Rudolph vein. They remind you that this is 1976, solidly in the late modernist era. But they are clearly, here, associated with the past, a failed and clunky modernism.

And they are windows onto a disappeared world, a subterranean one of darkness, earth and damp. The clarity, lightness, economy and openness to interpretation that define the house frames however – the ghost houses – is the main attraction. This is, quite literally, the outline of a postmodernist manifesto.

In his books Complexity & Contradiction in Architecture and Learning from Las Vegas (the latter written with his wife Denise Scott Brown), Venturi called for a tolerant architecture and an appreciation of popular taste. ‘Main Street,’ they wrote, ‘is almost alright’. In the ghost form of this house we see not only 18th-century Philadelphia but the form of every balloon-framed house in every suburb and exurb of the US. We see the McMansions and the tasteful New England barns, the clap-boarded holiday homes of Martha’s Vineyard and the over-sized houses which populate suburban horror movie franchises.

But there are so many other allusions. In its spectral form it seems to predict the 3D computer model, a thing absolutely there and somehow simultaneously unreal. It blends the absurd pop bigness of Claes Oldenburg with the sober and straight form of the house. It makes the everyday extraordinary, not by blowing it up but by dematerialising it.

The reconstructed 18th-century buildings scattered through Old City are still somehow fake – even with the patina of a few decades they still look like stage-set architecture, new heritage. Venturi’s intervention, though, looks as fresh and strange as ever. In a way, this non-building is an absurd thing to choose by an architect who built so much actual architecture. But in other way its haunting presence represents exactly how radically Venturi liberated modern architecture.

If I could pick anything to memorialise Robert Venturi I would pick a book, but this steel frame, sitting somewhere between a sketch, a model, an installation, a sculpture, landscape and a building, will do just fine. And, like the ghost houses, Venturi’s influence will continue to haunt our urban and architectural landscape.