|

|

||

|

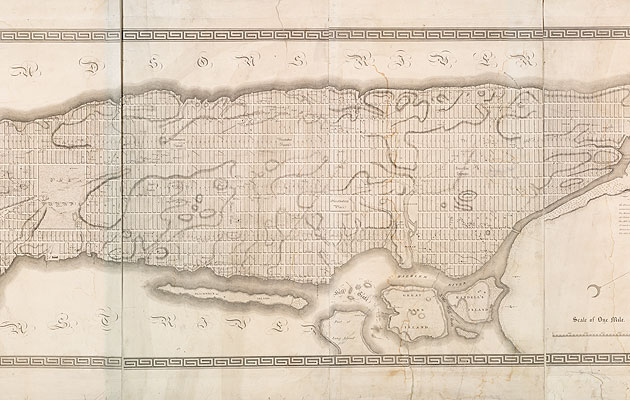

This year is the 200th anniversary of the Commissioners’ Plan for New York, the document that established the Manhattan street grid or, as Rem Koolhaas called it in Delirious New York, his “retroactive manifesto” for the city, ”the most courageous act of prediction in Western civilization.” In 1807, the Common Council of the City of New York granted three commissioners the power to “lay out streets, roads, and public squares, of such width, extent and direction, as to them shall seem most conducive to public good”. The plan they came up with four years later established 12 north-south avenues and 155 east-west streets. The commissioners remarked of their boldness: “It may be a subject of merriment that the commissioners have provided space for a greater population than is collected at any spot this side of China.” At this point, Manhattan’s population was 60,000, with settlement centred in the area below Houston (then known as North Street). So why was the plan, which took most of the 19th century to construct, so far-reaching? Andrea Renner of the Museum of the City of New York, where an exhibition devoted to the grid (curated by Hilary Ballon) is on until 15 April, explains that the population of New York was rising and “the commissioners were able to see that the Erie Canal, which was going to be put in place soon, would further the growth and [they wanted to] help the city grow in an organised manner.” Gridded cities were nothing new, from Miletus in the 5th-century BC, to local, recent examples such as Philadelphia. But the Manhattan grid was a speculative scheme in all senses, a move into hitherto uncharted territory. As Koolhaas puts it: “the land it divides, [is] unoccupied; the population it describes, conjectural; the building it locates, phantoms; the activities it frames, non-existent”. The commissioners didn’t plan for everything. Renner says: “The city the commissioners built was for horse and carriages, a city that depended on its ports, its rivers.” This explains why the streets so greatly outnumber the avenues and, also, the addition in 1836 of Madison Avenue between Third and Fourth, and Lexington between Fourth and Fifth. The plan put little emphasis on public space. This was partly due to the high price of land but also, the commissioners added, because “those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan Island render its situation … particularly felicitous.” This regard for the waterways seems to be one the city is regaining, with the opening up of the East River waterfront and the turning of Fresh Kills on Staten Island (Icon 101), Governors and Roosevelt Islands, into public spaces. The total nature of the grid is, paradoxically, what made it flexible. To make a new park or to establish a new square, all you had to do was join together two adjacent blocks. (These changes tended to be developer-led, as a new park raised the value of the land around it.) Most of the 20th-century reforms of the grid also concerned public space. It was Robert Moses, now the supervillain of New York City planning, who introduced superblocks – for housing projects and developments such as Lincoln Center. The argument the show at the Museum of the City of New York is trying to make, Renner says, is that what we think of as New York “came up precisely because of the grid”; that a city that doesn’t require you to learn street names is a metaphor for openness. And perhaps also that the streets, as determined by this 200-year-old grid, are the true public spaces of the city. The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011 is on at the Museum of the City of New York until 15 April 2012

|

Image NYPL

Words Fatema Ahmed |

|

|

||