The Modulor Man is a recurring silhouette in Le Corbusier’s buildings and art. Will Wiles looks back at this phenomenal form

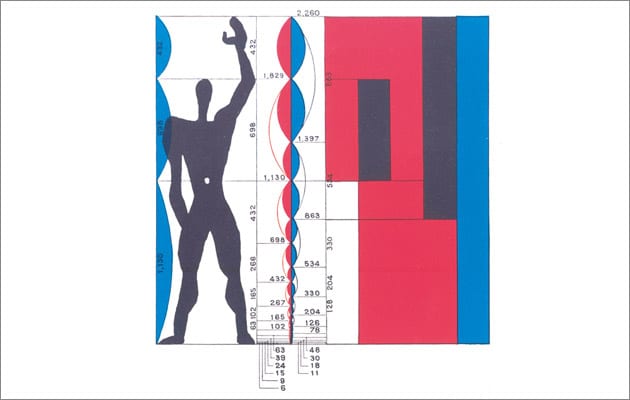

In Le Corbusier’s buildings and art a recurrent silhouette appears: the Modulor Man. It’s a stylised human figure, standing proudly and square-shouldered, sometimes with one arm raised, the mascot of Le Corbusier’s system for re-ordering the universe.

The Modulor was meant as a universal system of proportions. The ambition was vast: it was devised to reconcile maths, the human form, architecture and beauty into a single system.

Fibonacci and English crime novels

This system could then be used to provide the measurements for all aspects of design from door handles to entire cities, and Corbusier believed that it could be further applied to industry and mechanics. The modulor system had a series of scales and measurements, laid out in a modulor rule. The fundamental “module” of the Modulor is a six-foot man, allegedly based on the usual height of the detectives in the English crime novels Corbusier enjoyed.

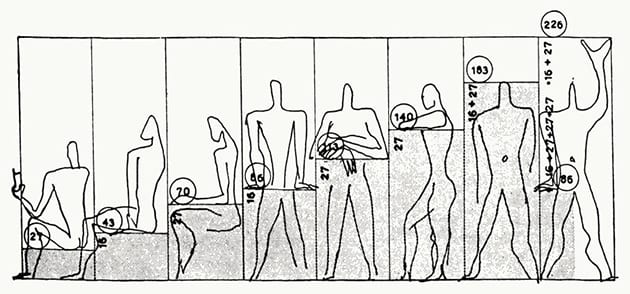

Another Modulor Man sketch by Le Corbusier

This Modulor Man is segmented according the “golden section”, a ratio of approximately 1.61; so the ratio of the total height of the figure to the height to the figure’s navel is 1.61. These proportions can be scaled up or down to infinity using a Fibonacci progression. In devising this system, Corbusier was joining a 2000-year-old hunt for the mathematical architecture of the universe, a search that had obsessed Pythagoras, Vitruvius and Leonardo Da Vinci.

The mystical virtues to the system

Le Corbusier developed the Modulor in 1943, and the first volume of his study on the topic was published in 1950. From the monumental concrete creation, Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles (completed 1952) onwards, Corbusier applied the Modulor to his buildings, including the government complexes he built in Chandigarh, India, and his rural retreat, Le Cabanon in the south of France. It won widespread praise, and was used by architects and designers including Georges Candilis and Jean Prouvé; no less a figure than Albert Einstein said: “It’s a tool that makes the good easy and the bad difficult.” But it was not widely adopted, perhaps because Corbusier wanted to patent the system and earn royalties from buildings built using it.

However, the fact that Corbusier showed Modulor to Einstein betrays how proud he was of his creation. Though the Modulor Le Corbusier said, was ‘a simple work tool, a tool such as aviation,’ he eventually became transfixed, attributing mystical virtues to the system and seeing it as part of the fundamental architecture of the universe itself. The quixotic search for a key that can unlock the secrets of architecture obsessed him, as it has others through the ages. The quest continues: architectural historian Charles Jencks, who has written extensively on Le Corbusier, identifies Peter Eisenman and Cecil Balmond as the inheritors of the spirit that drove the creation of the Le Corbusier Modulor.

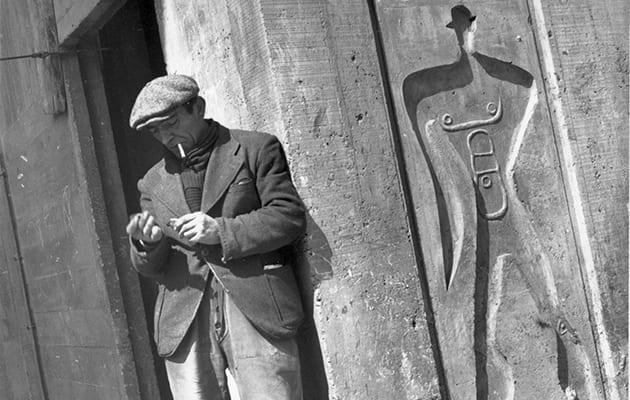

Le Corbusier stands with a concrete gliph of Modulor Man

The Modulor was, however, as arbitrary as any human measurement: its six-foot basis was plucked out of the air, there was no reason the Modulor Man couldn’t be five foot ten or six foot two. As is often said, a six-foot rule is hardly fair to women and children. Also, Corbusier’s own application of it was somewhat haphazard. Jencks points out that the children’s bedrooms in the Unité are six feet by 23 feet, not exactly an elegant proportion. If it’s flawed, if it never became the universal measure Corbusier wanted, why honour it? Why even remember it?

Human form at the centre of design

It goes without saying that things that are in proportion to one another are naturally more pleasing to the eye. But what’s really important is that the Modulor puts the human form back at the centre of design. In the present architectural climate of post-modern free-for-all, driven by computer processors and buoyed by parametric ideology, biomorphism runs riot, but human proportions are out of the picture. Maybe this is the result of an understandable discomfort with the idealisation of the human body. But we should overcome that discomfort to obtain the magical comfort of inhabiting spaces that we know were designed with our forms in mind.