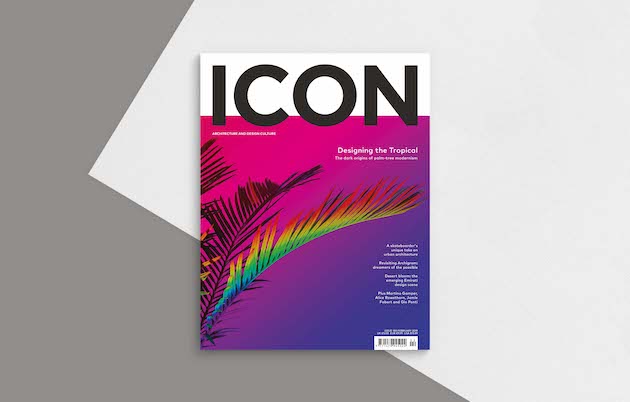

The new February issue of Icon, with cover art by Signe Pierce

The new February issue of Icon, with cover art by Signe Pierce

In this issue: the dark origins of tropical modernism. Plus revisiting Archigram, Jamie Fobert on the precise art of city-making, Martino Gamper in conversation with Alice Rawsthorn, and how skateboarders experience architecture as they traverse the city’s neglected corners.

A word from Priya Khanchandani, editor of Icon: From one perspective, decolonisation happened when the colonisers went home and the nations they had subjugated became free. The last wave was after the Second World War, when India, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco became independent, followed by many African states in the 1960s.

Only a handful of islands are still colonies today, but we all remain in colonialism’s shadow. In the last few years, we have begun to see – particularly in the cultural sector – that the process of decolonising was never fully resolved, as we never confronted the legacy of colonialism. Recently, we have begun to talk openly about decolonising everything from education to museums, Karl Marx and the kitchen sink.

Now it is time we put that talk into action. Institutions like museums which shape our reading of history, need to dismantle the power structures that formed their original foundations. Only through a rigorous process of decolonisation can design and the creative industries confront the structures of oppression that have influenced their development for more than two centuries.

![]() Jungle House in Guarujá, Brazil by Studio by MK27. Image courtesy MK27

Jungle House in Guarujá, Brazil by Studio by MK27. Image courtesy MK27

The potential for fresh perspectives on imperialist histories is immense. We have only scratched the surface when it comes to their impact on our understanding of design, architecture and culture. This cannot claim to be a cleanly “decolonised” issue of Icon – if such a state is even achievable in a post-colonial world. But it certainly tries to take a positive step forward. We have asked: how can we start to rethink design from a “decolonised” lens?

Tropical Modernism, for instance, finds form in trendy botanical architecture and palm wallpapers. But as our cover story explains, it has a darker side. As a design aesthetic it derives from colonial building methods, which enabled colonialists in tropical countries to deal with unfamiliar climates. In such contexts, modernist buildings were not just dwellings, they were an active and politically loaded part of the civilizing process, enabling medicine and hygiene to rescue colonialsts from tropical death.

![]()

Our profile of Indian designer Dashrath Patel, the story about a Ghanaian kente cloth and the Design Crime column critiquing the colonial object, represent post-colonial perspectives that must be voiced in the mainstream if, as a society, we are to have any hope of decolonising. These stories are intentionally placed alongside writing about Archigram, Gio Ponti, Jamie Fobert and other design stalwarts. They complement other progressive thinking about the material world, like the skateboarder’s unique experience of traversing architecture in the city.

This isn’t a special issue on decolonisation. It is a normal issue that shows decolonising doesn’t have to be a niche subject: it fits in here just fine. Making it mainstream is one way in which we can turn it from a theory into a flourishing, tangible reality.

Also in Icon 188:

Edwin Heathcote visits Houston to make his verdict on the Menil Drawing Insitute, an origami wonder adding to the remarkable cityscape forming at the Menil Collection.

![]()

Skateboarders have endured a testing relationship with municipal authorities but cities such as Malmö, Hull and Melbourne are seeing a future beyond antagonism. What can architects and the rest of us learn from this subculture that sees space and surfaces differently?

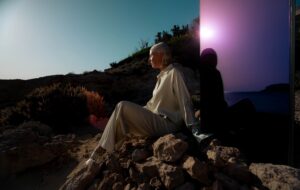

![]() Our skateboarding feature includes photography by Fred Mortagne

Our skateboarding feature includes photography by Fred Mortagne

And don’t miss the burgeoning design scene in the UAE, a conversation between Martino Gamper and Alice Rawsthorn, a profile of the late Indian design pioneer Dathrash Patel, an interview with Jamie Fobert on the gentle yet revolutionary future of our cities, and a double dose of Archigram as the visionary collective are remembered in a new tome.