|

|

||

|

The British Trads don’t get much attention from the modernist-dominated architectural establishment – it’s time they were given a platform There is a corner of British architecture that is new but forever traditionalist. It ranges from proper neo-vernacular rural buildings, through heavily Arts and Crafts-influenced houses with the odd dash of gothic revival, then on to full-on neoclassical chapels and churches, university buildings, office and apartment blocks, and of course grand country mansions. Brand new, but old-looking. The architects and designers of these structures are often superb restorers and adapters as well as new-builders. It’s time we stopped marginalising them. Actually, I’d say it’s time we started celebrating them. I’d like to set them loose on the British Pavilion at the next Venice Architecture Biennale. The British Trads don’t get much of a press from the modernist-dominated architectural establishment, something their more vocal members have been banging on about for years. Doomed to be forever unfashionable, and in these days of gender politics unfashionably male, theirs is not a kind of architecture that finds much favour with the architecture schools or awards panels. Though some of them engage with the profession at large, most don’t. They sit in their urban or rural studios and design away, untroubled by the opinions of their peers, usually not entering awards, occasionally not even bothering to obtain full professional qualifications. With the kind of loyal, well-heeled client base they can command, there’s not much need to go after the approval of fellow architects, who may be a bit hazy about the Orders, and a bit iffy about ornament generally. Partly this reticence is because of the 1980s style wars led by Prince Charles, who makes no bones of the fact that he likes this kind of stuff a lot and built the Dorset suburb of Poundbury to prove it. Partly it’s to do with the associated fact that supporters of the Trads tend to be on the political right – the likes of militant Tory philosopher-aesthete Roger Scruton or the architectural historian David Watkin. And then there’s the unavoidable fact that in the 20th century, the classical style was the tyrant’s style of choice, and so became closely associated with totalitarianism. Albert Speer and Joe Stalin left long shadows. Today it is a style beloved of oligarchs. But you can’t blame Palladio or Vitruvius, let alone Hawksmoor, Soane or Adam, for them. Architecture is a profession that – with the occasional startling exception such as Patrik Schumacher of Zaha Hadid Architects – broadly tends to be centre left in outlook. As, I suppose, am I. But I’ve always been fascinated by the Trads: the differences between them; the craft skills their buildings encourage; the emergence of a younger generation in recent years; the fact that you can see their architecture evolving. Trad architecture now, for instance, isn’t much like Trad architecture of the 1950s. It may draw on Ancient Greece and Rome for its inspiration but it inhabits the same world of building regulations and new technology as every other approach – with added drawing beauty. It helps architectural biodiversity. You need as many species as possible. You need to avoid monocultures. And given that architecture is so very pluralist right now, with everything from brutalism to pomo on the agenda, shouldn’t the Trads be encouraged, not ignored? Something of a schism happened this year when Quinlan and Francis Terry, father and son, parted company, with Francis setting up his own practice competing with his dad’s. That’s one to follow. London-based Demetri Porphyrios is in demand internationally. Ben Pentreath has long moved from interior design to full-blown architectural design. Never heard of Stanhope Gate Architecture? Run by Alireza Sagharchi, it’s something of a Trad powerhouse. As is Adam Architecture, a big firm with six individually talented directors, only one of whom is Robert Adam. Then there are soloists like Ptolemy Dean, who is adding a new gothic building to Westminster Abbey. Wales-based Craig Hamilton is seen by some as the best of the lot. So this architecture manages to be simultaneously part of the mainstream and cultish. My modest proposal is that its practitioners should be asked to take on one of the most difficult jobs in architecture: the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. This is a very formal, up-on-a-plinth neoclassical villa that everyone has always struggled to make work as a satisfactory exhibition venue. But it should be meat and drink for them, especially given the challenge of Venice itself. The British Council, which runs the pavilion, has always liked to seem progressive, forward-looking. Well, this would not represent retrenchment – the classical approach is the most universal and flexible language in architecture. Bring on the Trads! Hugh Pearman is editor of the RIBA Journal |

Words Hugh Pearman

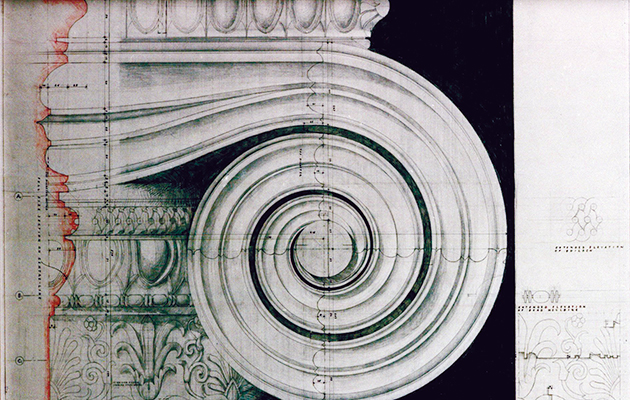

Above: Pencil drawing of an Ionic capital by Francis Terry, 2004 |

|

|

||

Last year’s British Pavilion exhibition, Home Economics, struggled in its Palladian home