Rael San Fratello’s seesaw installation on the US-Mexico border wall. Photo: Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello

Rael San Fratello’s seesaw installation on the US-Mexico border wall. Photo: Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello

A silent profession, writes Ana Karina Zatarain, has proved ineffective in improving migrants’ quality of life.

At the border where Ciudad Juárez, Mexico meets El Paso, USA, a professor of architecture at Berkeley named Ronald Rael installed a series of fluorescent pink seesaws last July. Each half hovers the ground of its respective country, waiting for children to activate the structure. Depending on where you fall along the cynicism scale, it can be read as either endearing or sinister, but one fact is clear: it does little to resolve the suffering of the thousands of migrants who are detained along that divide.

Art often eschews pragmatism. It can be argued that thought is what drives an artist’s practice, that observing the world around them and producing physical interpretations is the very definition of art-making, and that those objects can go on to shape the narrative and our collective understanding of society and ourselves. But is that enough? Political art can function as a catalyst for change through activism, but existing on its own as an object, it cannot fix the world.

Architecture, on the other hand, is burdened with the very real obligation of improving our quality of life. And yet, where migrants are involved, architects have so far proven to be as ineffective as the brightly-coloured seesaws lining the border. Though the response to the installation was overwhelmingly positive (‘Making the best out of division!’, declared one user on Twitter), there were also mixed feelings, especially coming from architects and critics. ‘I’m an optimist so the seesaws are harmless/cute/endearing,’ tweeted Anjulie Rao, an architecture journalist based in Chicago, ‘but yes [was this stated as yes or yet in the original text?] they don’t do much to address the horrific results of a militarized border wall nor do they elicit enough empathy to compel people to think critically about what it means to be a neighbour.’ In response, Gabrielle Printz, also an architecture critic, stated that ‘the wall is part of the joke – they are setting it up to seem absurd, not violent.’

Art installations do nothing to resolve the suffering of detained migrants. Image: Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello.

Art installations do nothing to resolve the suffering of detained migrants. Image: Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello.

I’ve lived on both sides of the border wall – though mostly, and currently, south of it – and the installation struck me as a saccharine gimmick, perhaps unintentionally cloaking a humanitarian crisis in a feel-good narrative of playful cause-and-effect. Architects and those who write about them tend to be swift and unforgiving when expressing outrage, myself included. This particular case, though, led me to wonder what the design community is doing to actually address the migrant crisis.

Because camps that hold migrants have so far been mostly improvised from pre-existing structures (like an old Walmart in Brownsville, Texas), it has been easy for architects to wash our hands of responsibility. But if architecture is primarily concerned with the living conditions of communities, how can we turn a blind eye to the suffering of immigrants in crowded, windowless spaces? And if these spaces were ideal, would we as architects be free of the responsibility to speak out against human detention? Where can we draw the limits of our moral obligations to society?

Last summer, The Architecture Lobby and ADPSR (Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility) issued a statement urging a total boycott of all design-related work for immigrant detention centres. In response, Dana McKinney, an architectural designer at Gehry Partners in Los Angeles, said that ‘although this position is understandable, and in some ways admirable, now is not the time for designers to abdicate their professional and ethical responsibilities,’ adding that ‘instead of refusing services in building detention facilities, design professionals should take the lead and devise alternative environments to house immigrants with dignity.’

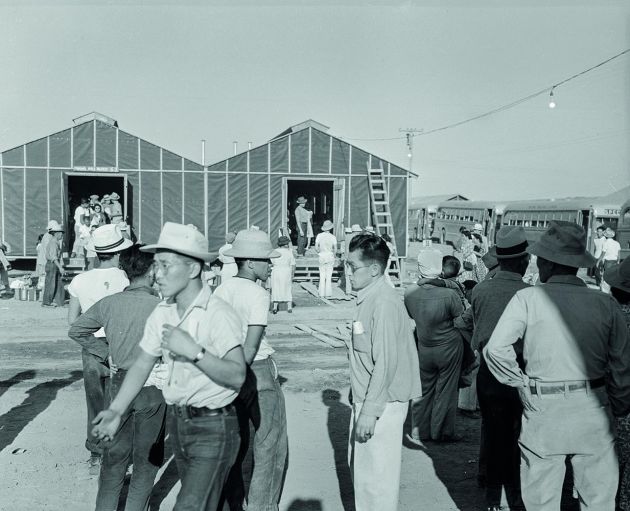

Japanese-American detainees at the Poston War Relocation Center, Arizona. Photo: Alpha Stock / Alamy.

Japanese-American detainees at the Poston War Relocation Center, Arizona. Photo: Alpha Stock / Alamy.

This is not the first time that such idealistic logic has been applied to detainment camps. In 1942, the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi voluntarily committed himself to living in the Poston War Relocation Center, the largest of ten American concentration camps built to incarcerate Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. Noguchi had previously met with John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs – which was in charge of building and running the camps. Together they devised a utopic masterplan for Posten, based on the fact that given there was no way to prevent internment from happening, they may as well make it idyllic. When Noguchi arrived, however, it became clear to him that local authorities had no intention of improving the prisoners’ living conditions and he was detained there against his will for seven months. None of his proposals for the site were ever realised.

The fact is that the spaces that house unwanted people of a certain race or nationality are intentionally bleak. For the authorities who insist on the necessity of such camps, the misery of their inhabitants is not a bug. It’s a feature. Nobody is able to add dignity to an inherently inhumane endeavour.

For architects to simply boycott the design of immigrant detention centres is also laughable. Our profession knows – or should know – better than any other just how much a person’s living conditions will affect them, physically and psychologically. A collective refusal to work with the US government, just like pink playground equipment, is not enough. As a profession, we should be spearheading the call to abolish the camps at the border.