|

|

||

|

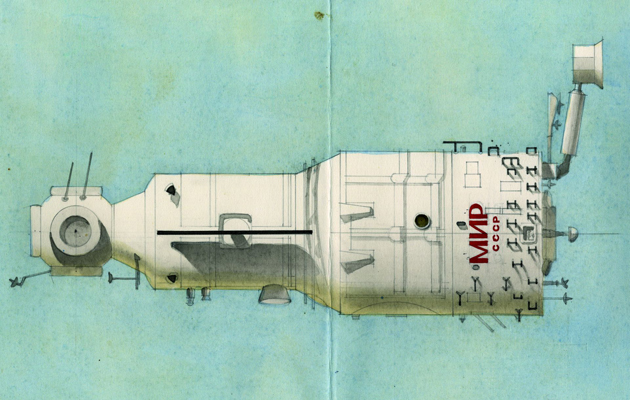

One architect defined the look of the whole Soviet space programme, from its logos to its satellites. Edwin Heathcote is fascinated by her personal archive Galina Balashova, born in 1931, began her career as an architect by stripping off the decorations from Stalinist buildings that had fallen foul of the Khrushchev reforms. The classical language of socialist realism was firmly out by the mid-1950s when she started, but the designs still had to get built. Just a bit less frilly. She finished her career in the early 1990s as the pre-eminent architect of space exploration. It is quite a trajectory. Balashova began working for OKB-1, the Soviet space agency, designing residential buildings for the scientists and engineers working on the space programme. As the only architect in the team, she was then poached by the boss, Sergei Korolev, to work on the interiors of the manned spacecraft that came in the wake of Yuri Gagarin’s first brief space flight in 1961. This book compiles Balashova’s watercolours of space-capsule interiors, furniture, control panels, ergonomic studies and the vast paraphernalia of the space programme, which embraced everything from badges and logos to stationery and satellites. Balashova did it all. There are some striking insights into design for zero gravity. It was thought, for instance, that in zero-gravity conditions, cosmonauts wouldn’t bother about orientation in the spacecraft, but Balashova realised it mattered and, in a semiotic coding, introduced colour schemes that ensured floors were always dark coloured and ceilings light so cosmonauts could get their bearings. Furniture was designed to look domestic rather than space age. While production designers were playing with tin-foil and moulded plastics, Balashova designed glass-fronted sideboards, check-blanketed built-in beds that looked like they would belong on a river barge, and radiogram-style control panels. The domesticity, however, is deceptive: these were stripped, high-tech machines that trampled over their flashier American counterparts. The complex interiors of the first Mir space station – launched in 1986 to serve as mankind’s first permanent presence in space – with their ingenious vertical sleeping capsules, were, for instance, meticulously planned by Balashova. What is surprising here is the sheer range of the architect’s work. From interiors and space furniture to the graphics on the sides of spaceships and on the inevitable Soviet medals, Balashova’s hand is everywhere. Her impeccable watercolour renders completely defined the image of the Soviet space programme, in space, on Earth and on stationery. She was a trading machine. Balashova’s own recollections about her role in the space programme are here, portrayed deadpan and, frankly, badly written. The most touching moment is when she relates how the team suddenly realised that there was no decoration on the spaceship walls. Balashova was invited to paint a series of pictures and she responded by painting the remembered landscapes of her childhood, which she thought would be a reminder of home to the cosmonauts. “These pictures”, she relates, “no longer exist, since they were incinerated with those parts of the spacecraft that burn up during landing.” The only reason her remarkable drawings survived is that, as there was no architecture and design department (except for Balashova herself), there was no architecture and design archive. So, despite their classified nature, she was allowed to take them all home. The book concludes with a collection of her post-retirement watercolours, including portraits of her family in traditional costume and landscapes. They are execrable.

LOOKING EAST Architecture behind the Iron Curtain is all the rage. Try these for starters: Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings The latest magnum opus from the leading architecture critic – a grand, messy travelogue round the urban ambitions of the socialist state, which ends up as a paean to the pleasures of observation. Soviet Bus Stops Photographer Christopher Herwig tours 14 ex-Soviet states, recording a diversity of approaches to the humble bus stop, ranging from extravagant concrete shards and modernist polygons right through to traditional headgear and mosaic shells. Radically Modern: Urban Planning and Architecture in 1960s Berlin For those hoping to embrace both east and west, this is an extraordinarily rich source of material revealing the diverse paths towards utopia taken by architects and planners in the two Berlins after the construction of the wall in 1961. |

Words Edwin Heathcote

Galina Balashova: |

|

|

||