|

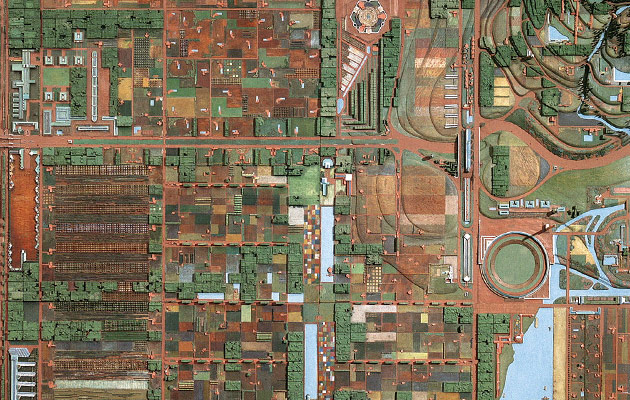

Broadacre City (image: MoMA, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) |

||

|

A display of Wright’s thinking about cities, in New York until 1 June, reveals the conflicts and convictions of his urbanism Frank Lloyd Wright is much less celebrated for his thinking on cities and urban planning than as an architect. Urbanists tend to slight him for his influence on the post-Second World War suburb, most notably through his masterplan for Broadacre City. In this polemical 1934 proposal, he called for dispersed homesteads, with highways stretched over agrarian landscapes, high-rise office buildings, and a decentralised building ratio of one acreage per residence. The lofty plan was never realised (at least not directly), yet the post-war building boom of automobile-centered communities led many to regard Wright as a prophet of the now much-maligned American suburb. More critically, however, the work crystallised Wright’s unresolved thinking on vertical and horizontal development. An exhibition at MoMA, Frank Lloyd Wright and the City: Density vs. Dispersal, explores this tension in his views towards the growing American city, from the 1920s to 1950s. Co-organised by Barry Bergdoll and Carole Fabian, director of Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, the exhibition draws on rare materials from a recent joint acquisition of Wright’s extensive archives: a mixed-media batch of sketches, publications, videos and models. A chronology of projects neatly lines the gallery perimeter — most Wright’s 1952 HC Price Company Tower, a 19-storey structure built on prairie lands of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, realised his protean ideals for both density and sprawl to an extent – second to the tower, the city’s tallest building was a three-storey church. The collection of work culminates in a 8ft-long sketch of the Mile High skyscraper, designed for Chicago in 1956 – capable, the architect claimed, of housing 100,000 of the city’s residents. All the while advocating high-rise structures, Wright asserted that technological advances – the automobile, the telephone, the telegraph – were on the verge of rendering population-dense cities obsolete. We can begin to sense his resistance to the lateral density of cities as early as 1926, when he devised the Skyscraper Regulation: a set of design rules drafted in response to the “congestion” caused by unregulated building booms in New York and Chicago. These rules set out to govern the growth of cities through traffic flows that separated elevated walkways from ground-floor roadways; green spaces placed to conceal parking garages, and skyscrapers pushed to the perimeter. But within a few years, he would feel compelled to no longer negotiate the city as inherited, but propose an entirely new plan. Centre-stage in the gallery is his 1934 tabula rasa – a looming, 12ft-square plywood model of Broadacre City, worn from frequent exhibition travel in the 1940s and 50s. Even in its scaled-down, miniature representation of a sample four-mile plot, its exaggerated proportions make a case against itself. A modern embodiment of Manifest Destiny, it also presents itself as a rebuttal to Le Corbusier’s own manifesto-as-master-plan, Ville Radieuse, which had offered typologies for strictly zoned, high-density urban housing just a few years earlier, in 1924. While Le Corbusier considered a house “a machine for living in”, Wright’s vision was decidedly darker: “We live now in the cities of the past,” he wrote in his 1932 book, The Disappearing City, “slaves of the machine and of traditional building.” |

Words Aileen Kwun

Frank Lloyd Wright and the City: Density vs. Dispersal |

|

|

||