|

|

||

|

Will Wiles was gripped by an exhibition at the Wellcome Collection that exposed the links between art and crime like luminol on a blood-spattered carpet One of the really striking aspects of the long-running American police drama CSI: Crime Scene Investigation is the way that it accents and stylises the more visible aspects of criminal forensics, turning them into a kind of ritual art, and giving science some of the glamour of magic. Particularly memorable are scenes in which coloured string is used to trace the course of bullets and blood droplets through the air, creating spatial reconstructions of a past event that are suggestive of futurist motion art. It is an apt symbol for the whole business of forensics, tracing all these scattered fragments back through space and time to re-assemble a single explosive moment of violence. But the show’s signature act is the spraying of a substance called luminol over an ostensibly “clean” scene, and then using ultraviolet light to reveal the organic proteins still indelibly adhering to every surface – a rave lightshow of human fallibility and mortality, and an obsessive compulsive nightmare. So magical is the effect of luminol that it is almost surprising to find that it really exists, and is not just a TV writer’s fantasy. And it is no surprise at all to find it used as the basis of art, specifically Angela Strassheim’s Evidence photographs, which are included in Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime, a free exhibition at the perennially diverting Wellcome Collection. Forensics combines historical artefacts explaining the history of this arcane trade with examples of the way crime, violent death and investigation have been used by artists.

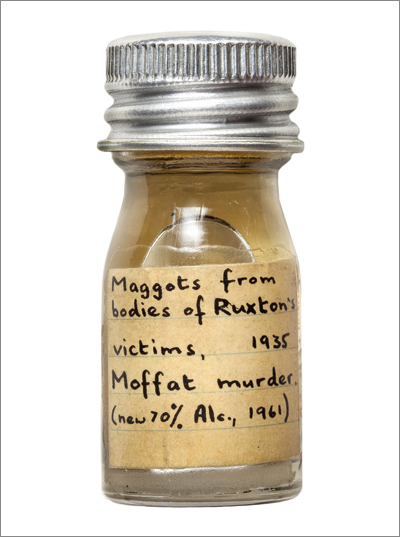

Maggots from the bodies of victims of Buck Ruxton, a Lancashire doctor who murdered two women in the 1930s What becomes obvious very quickly is that, while there might not be all that much art directly involving forensics, a great deal of modern art is forensic. Mexican artist Teresa Margolles’s 32 años: Suelo donde cayó el cuerpo asesinado del artista Luis Miguel Suro, for instance, is a slab of white-tiled floor that immediately suggests Gordon Matta-Clark’s Bronx Floors. But, whereas Matta-Clark’s scuffed lino is poignant and melancholy, Margolles’s stained tiles are unbearably intense: it was on this floor that an artist friend of hers was found murdered. And there is much in forensics that suggests artistic practice. It involves recording and looking and seeing: the word “morgue” derives from the French for “to peer”, and “autopsy” from the Greek “to see with one’s own eyes”. Its history is entwined with that of photography, and investigators are often photographic pioneers. In the early 20th century, for instance, Alphonse Bertillon invented the “God’s eye” camera angle, using a very tall tripod to suspend a camera directly over a corpse, giving “a unique perspective on the body in relation to its surrounding and an additional opportunity to scrutinise peripheral details”. Bertillon also pioneered the modern “mugshot” record of suspects’ facial features. One of the unexpected things about the history of forensics is how much of it has been made by the French, and in particular by the extraordinary polymath Edmond Locard, founder of the first police crime lab.

A knife recovered from a murder scene Five rooms cover “The Crime Scene”, “The Morgue”, “The Laboratory”, “The Search” (for missing people and for the identity of found remains) and “The Courtroom”. There are the kinds of ghoulish souvenirs you might expect, such as bits of evidence from the Crippen trial or centuries of beautiful yet grisly illustrated manuscripts examining the effect of injury, death and decay. But there is also much unexpected material, such as an extraordinary diorama of a fictional crime scene resembling a crime novel in doll’s house form. It is one of 20 made by the eccentric heiress Frances Glessner Lee in the 1940s as a tool for training investigators – amazingly, they are still in use today. The exhibition ends, perfectly, on Taryn Simon’s photos of wrongly imprisoned men, taken in locations related to their unjust conviction: a reminder that all this artistry and science can serve fiction as well as fact. Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime at the Wellcome Collection in London ended on 21 June 2015

A fly specimen |

Words Will Wiles

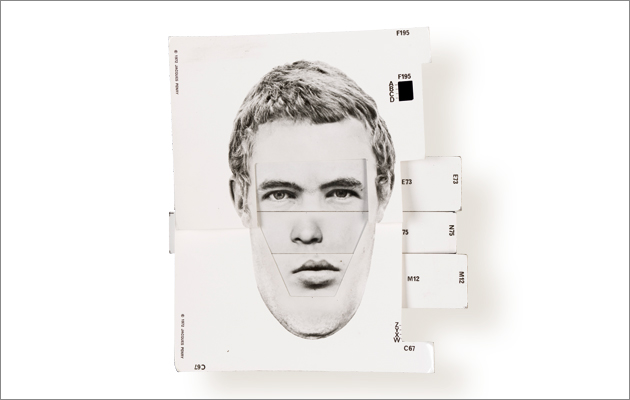

Above: A Metropolitan Police photo fit |

|

|

||