|

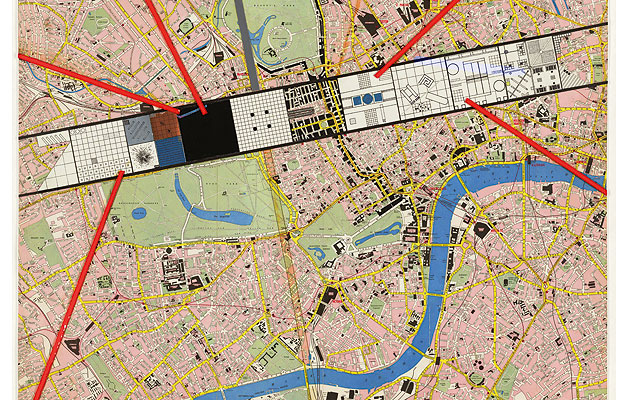

Exodus by Rem Koolhaas, 1972 (image: Rem Koolhaas) |

||

|

The latest album by Britney Spears, released in November, is a collection of her hit singles, retelling the meteoric rise to stardom of the troubled pop princess. Its ad campaign features the iconic image from her first single, a pigtailed 17-year-old in school uniform. After years of navel-gazing and grunge, Baby One More Time (1998) reworked the principles of modern pop, returning it to its previous glory as the dominant music of the day. Down in Bedford Square the Architectural Association’s new exhibition provides a similar piece of myth-making for the modern starchitects, including the school’s own illustrious alumni. The exhibition presents the “First Works” by 20 practices which have collectively defined the contemporary architectural scene. Commencing with the North Penn Visiting Nurses Association Headquarters (1960) by Robert Venturi, 35, and concluding with the Blue House (1979) by Herzog, 29, and de Meuron, 29, the exhibition includes ten first buildings and a selection of competition entries, graduate theses and speculations. Chronologically squeezed into the ground and first-floor galleries, it provides an opportunity to see the original drawings, models and photographs alongside contemporary models and press. Reading the schemes in the original removes the historical hyperbole, allowing the work to be seen simply as a representation of the architects’ concerns. A sublime “manifesto against repetitive social housing” in the Philippines by Steven Holl, 27, demonstrates a social engagement and interest in the process of production that belie his subsequent focus on form. Photographs of a distinctly prosaic document – crude type, small illustrations, black plastic ring binding – reveal a bias for narrative content over form in Exodus (1972) by Rem Koolhaas, 28, and an embryonic OMA. With 40 years’ hindsight it is dangerously easy to read each work as the DNA for the architect’s subsequent career. Writing today about the dense line drawings of his “Micromegas” (1978), Daniel Libeskind, then 32, claims: “When I look back at these drawings they contain my subsequent spatial discoveries and even technical details. I have found whole complex masterplans in them.” Post-rationalisation is a familiar tool for architects and given the singularity of his built aesthetic may have some credibility in this case. Yet it is harder to see how the temporal provocation of Bernard Tschumi’s Fireworks (1974) informed his new Acropolis museum or the dematerialised sensuality of Coop Himmelb(l)au’s Villa Rosa (1967) provided a starting point for its 2006 Mercedes-Benz museum. In his introduction to the catalogue the AA’s chairman, Brett Steele, suggests the show is “a re-examination of how to begin a critical architectural practice”. Having co-founded a company in 2005 that aspires to critically engage with architecture and its practice, I avidly looked beyond the assembled material for clues to a successful beginning. For getting the jobs and paying the bills, establishment connections seem useful: Cedric Price, 27, won his first significant commission, the London Zoo Aviary, with Lord Snowdon. Family generosity seems similarly beneficial, whether it leads to a commission for a rural retreat for your parents-in-law (Rogers, 30 and Foster, 28) or a 20,000sq m factory for your dad’s mates (Moneo, 27). If you fail to take the opportunity to use your graduate thesis to set the world alight (Archigram founder Webb, 24, Archizoom founder Branzi, 28) then competitions seem a key opportunity to explore and define your position in public. With her proposal for a residence for the Irish prime minister Zaha Hadid, 29, established both the signature painting style and quality of interiors that would define her subsequent career. Yet when the positioning and rhetoric are stripped back Toyo Ito seems to summarise the real essence of beginning a practice, then as now. “I’m amazed how I managed to sustain my office, which always had two or three staff members, when for more than ten years I was only able to secure small jobs. It sounds rather difficult, but in a certain sense my life was filled with joy and satisfaction I’d never experienced before. Day and night, I sat in front of a drawing board and drew. Next to my desk there was a record player endlessly playing Japanese hit songs.” I like to imagine today it would be playing Britney.

Blue House by Herzog & de Meuron, 1979 (image: Herzog & de Meuron)

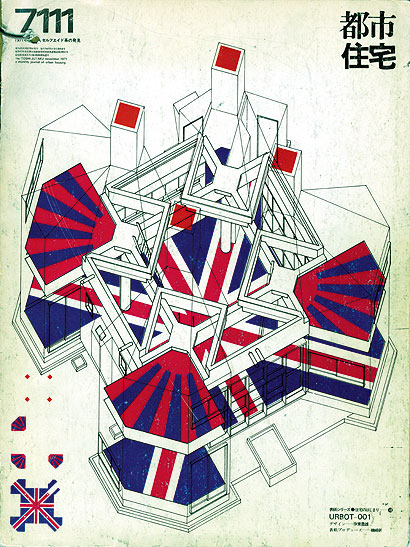

Aluminium house by Toyo Ito, 1970, on the cover of Toshi-Jutaku (image: FRAC)

Aluminium hous by Toyo Ito, 1970 (image: Yukata Suzuki Photo Atelier) First Works: Emerging Architectural Experimentation of the 1960s & 1970s is at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, London, until 13 February 2010 |

Words Geoff Shearcroft |

|

|

||