Green fields, blue skies and nostalgic architecture: the fossil fuel advertising of 20th-century Britain inspired delusion. Now we are not such willing participants

Poster by Edward McKnight Kauffer for Shell, c 1936. Image via Flickr creative commons

Poster by Edward McKnight Kauffer for Shell, c 1936. Image via Flickr creative commons

Words by Emma Draper-Coates

Fossil fuel companies may have been formally excluded from COP26 and campaigns to ban fossil fuel advertising are proliferating (the latest a European Citizens Initiative sponsored by Greenpeace), but the marketing departments of Big Oil aren’t going down without a fight. After all, they’ve spent over a century building brands that present the relentless extraction and sale of oil as edifying public service.

In 1928, a consortium of the major Western oil companies conspired to fix global oil prices and respective market shares in a secret pact known as the Achnacarry Agreement. Consequently, the best way for companies to increase profits was to expand demand for their products, and they did this by encouraging more people to drive to more places.

Throughout the 1930s, a series of Shell poster campaigns by celebrated artists such as Paul Nash, Vanessa Bell and Graham Sutherland showcased the delights of the British countryside and inspired motorists to visit lesser-known rural landmarks, all under the strategically vague strapline: YOU CAN BE SURE OF SHELL. These images didn’t make concrete claims about the quality or price of the company’s petrol; instead, they were part of a holistic branding exercise that would identify Shell with the wholesome values of nature and art in the eyes of the British public for decades to come.

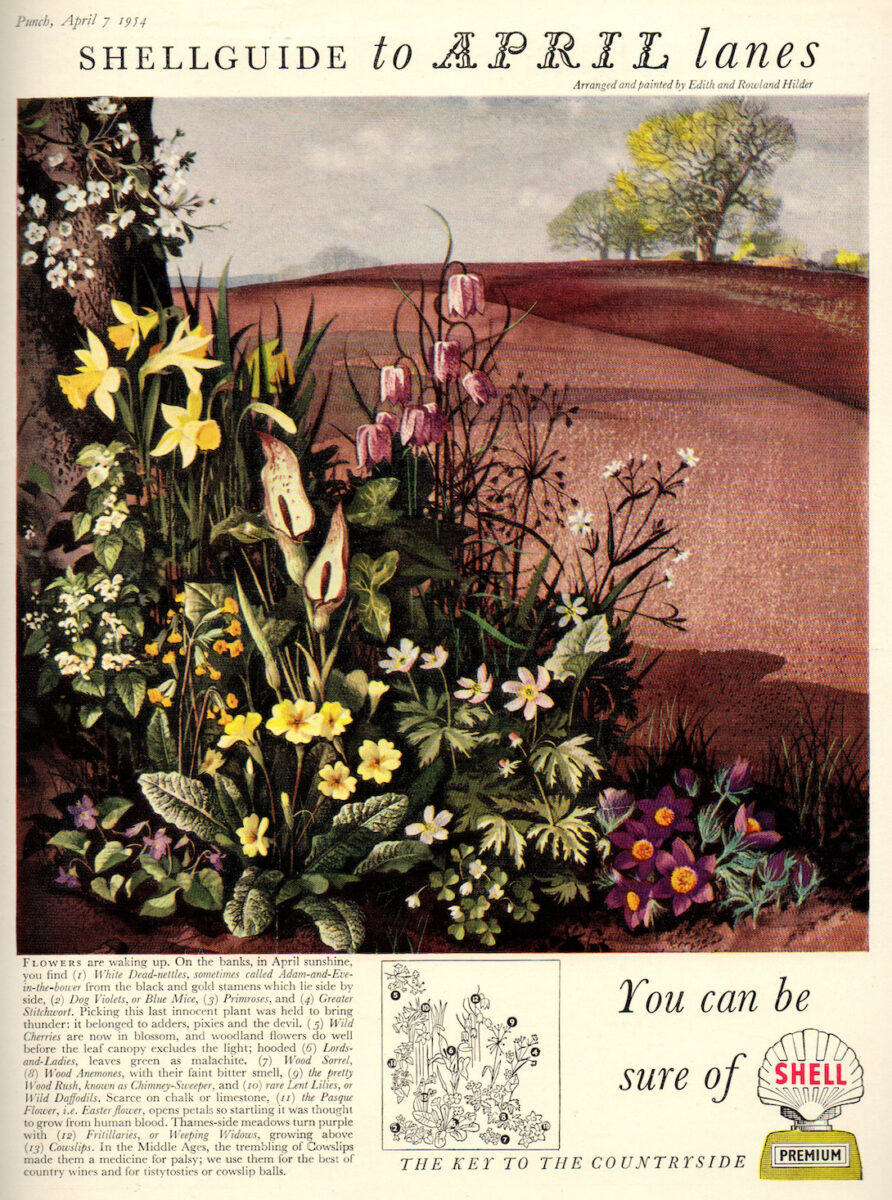

Shell guide to the countryside, painted by Edith and Rowland Hilder, 1954. Image via Flickr creative commons

Shell guide to the countryside, painted by Edith and Rowland Hilder, 1954. Image via Flickr creative commons

Global warming may have been but a distant twinkle in a climate scientist’s eye at this point, but there were already growing concerns about the environmental impact of motoring, specifically the aesthetic damage and disruption it wrought on the British countryside. The inter-war period saw a new preoccupation with rural preservation and a fanatical adherence to the idea of Britain as green-and-pleasant land.

By producing advertising that was simultaneously deeply nostalgic and vehemently modern, Shell cleverly positioned itself as a company that could be all things to all men. Traditional British landscapes and landmarks were portrayed in exciting contemporary artistic styles, and while the posters extolled the joys of motoring, the imagery they contained was pristinely free of all the accoutrements of motor tourism (cars, roads, petrol stations, car parks) that so disturbed the conservationists.

This untroubled image of oil companies as benevolent tour guides continued for some time. In the 1960s, a joint marketing venture between Shell-Mex and BP produced the wildly successful ‘Shilling Guides’ – illustrated booklets detailing the history, landscape and main attractions of every county in Britain. But by the 1990s, the devastating impact of burning fossil fuels on the environment had been firmly established and the public had begun to sit up and take notice. Major oil companies subsequently embarked on various corporate greenwashing campaigns intended to secure consumer trust and prevent investor flight.

Many of these campaigns, including Shell’s ‘Let’s Go’ (2010-12) and BP’s ‘Possibilities Everywhere’ (2019), have required heroic efforts of doublethink on the part of the viewer. Kites soar through pure blue skies, a young girl enjoys a cosy bedtime story, a baby laughs in his car seat. Accompanying text describes the companies’ valiant efforts to produce clean energy and furnish us all with a sparkling bright future. We are still being told that Big Oil represents safety, security and innocence as well as ground-breaking science and bold leaps into the unknown.

Shell billboard illustrated by Paul Slater. Image via Flickr creative commons

Shell billboard illustrated by Paul Slater. Image via Flickr creative commons

Yet very few of the major oil companies seem inclined to pivot dramatically away from their legacy business models. Shell plans to reduce its oil output by just 1-2% per year, meaning that by 2050 it still intends to be producing about a million barrels of oil a day. Total has announced that it intends to maintain its oil output at current levels. ExxonMobil may have invested $10bn over the past 20 years in researching ‘lower emission energy solutions’, but it spent more than that in 2020 alone developing new untapped oil and gas reserves. The International Energy Agency has been starkly clear that any new coal, oil or gas development will make achieving the ‘net zero by 2050’ target an impossibility, yet all the major European and US energy companies continue to invest more in oil and gas development than in renewables development.

But perhaps we are all becoming less willing participants in the fictions of Big Oil, with the industry’s ad campaigns facing an increasing number of legal challenges over the last 15 years. In 2007, the Advertising Standards Authority ordered the removal of a Shell advertisement featuring imagery of refinery chimneys spewing out streams of colourful cartoon blossoms, a retro 70s typeface and a claim that Shell uses its waste carbon dioxide to grow flowers. The ASA wearily reported that the actual proportion of CO2 used for that purpose was ‘very small’.

Calculated corporate appeals to our nostalgia for the good old days are less and less likely to wash as a new generation of media-literate children come of age in a warming world. If Big Oil is serious about reputation management, they might need to start putting their money where their mouth is.