First Nations people in Canada still suffer from unacceptable housing conditions – and that needs to change. How can architecture play a role in reconciliation?

View of the exhibition Caroline Monnet: Ninga Mìnèh at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley

View of the exhibition Caroline Monnet: Ninga Mìnèh at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley

Words by Caroline Monnet

The abhorrent housing conditions faced by many northern Indigenous communities in Canada have sadly remained unchanged for years. The Canadian government has been responsible for providing housing for First Nations people and unfortunately, has done a bad job. The high cost of construction materials, coupled with poor civic planning and lack of vision from the Canadian government, has resulted in the construction of stick-built housing styles of the suburbs that are not suitable in the frozen cold north and which bear no resemblance to traditional First Nations dwellings.

This housing crisis has plagued First Nations reserves in Canada for decades and is worsening with each passing year. Since 1876, when the Indian Act first forced First Nations people to live on reserves, the federal government has been responsible for providing their housing. The root of the Canadian system and its relationship with First Nations was the idea that they would not survive as a people and that housing on reserve would be a temporary fix.

Winter temperatures often dip below minus 30 degrees celsius, and people are living in homes without heat or reliable electricity. Some even live in uninsulated sheds. Rampant mould is seriously damaging people’s health. Most First Nations people cannot afford better because 80% of reserves have median incomes below Canada’s poverty line. The Indian Act ‘reserved’ Crown-held land for First Nations and the government took the rest for itself, thus creating a reservation system that to this day prohibits First Nations people from owning land. That means they have no assets to secure mortgages and need to front 100% of their building costs, which can surpass normal market value due to the remote locations of many reserves.

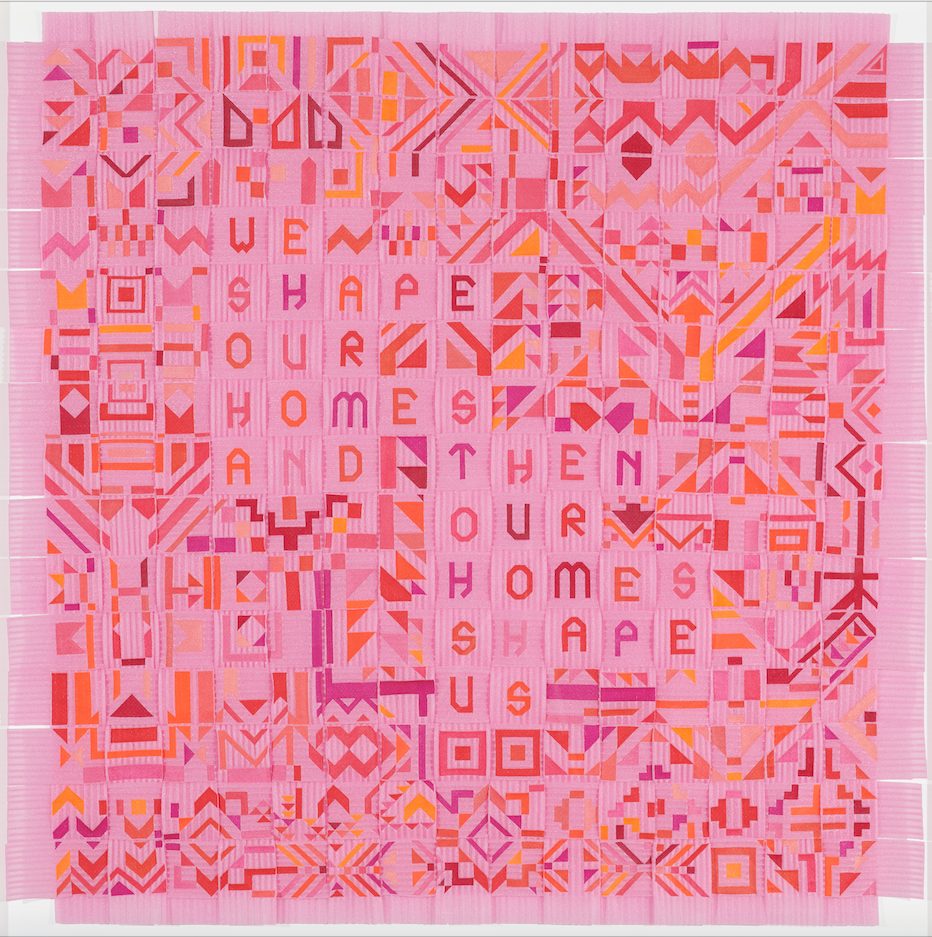

We Shape Our Homes and Then Our Homes Shape Us, 2021, by Caroline Monnet. Courtesy the artist, MMFA, Jean-François Brière

We Shape Our Homes and Then Our Homes Shape Us, 2021, by Caroline Monnet. Courtesy the artist, MMFA, Jean-François Brière

Furthermore, overcrowding in First Nations communities is a longstanding issue in Canada. In 2019, a United Nations report on housing for Indigenous populations found one in four people on reserves were living in overcrowded conditions. This troubling figure is approximately seven times that of non-Indigenous people across Canada. After years of failed federal projects, First Nations people are clamouring for greater autonomy and more concrete solutions.

As an artist, I use raw materials to tell the story of Indigenous identity, culture, traditions and despair. My art interweaves building materials with intricate patterns inspired by traditional Anishinaabe iconographies connected to my mother’s Indigenous heritage. I retrace these roots to portray Indigenous history as an evolving and dynamic negotiation between the traditional and the modern.

My recent exhibition Ninga Mìnèh (meaning ‘promise’ in the Anishinaabemowin language) calls attention to this social crisis through conceptual artworks that combine traditional motifs with domestic building materials such as Styrofoam, gypsum and insulation. My hybrid work reflects how a house embraces spirituality and is an extension of our bodies; when there is no sufficient housing, it breaks our physical and emotional wellbeing. Taking inspiration from traditional designs found on birch bark baskets and beadworks, industrial materials transform into poetic and organic shapes through weaving and embroidery. Every surface offers the potential for re-instilling cultural pride in materials and opening a dialogue about the current housing crisis in First Nations communities.

Caroline Monnet. Photograph: Ulysse Del Drago

Caroline Monnet. Photograph: Ulysse Del Drago

The birch bark biting technique, unique to my Anishinaabe ancestors, allows for intricate designs that use geometry and symmetry. With that in mind, I create my own patterns, elaborate them on the computer, and mirror my urban and contemporary reality. The patterns start resembling city maps and QR codes while remaining true to the weaving and beading that inspire them. They act as microchips that transfer ancient knowledge buried deep down across generations, offering a glimpse back and a path forward. They have become a language of their own, referring to the fact that I’m a direct link to the colonial project that began 500 years ago.

For Indigenous communities, architecture has never been seen as something friendly. It’s a symbol of colonisation, representing sedentary life, residential schools and on-reserve housing. What if Indigenous communities were able to develop their own housing models? How can architecture play a role in reconciliation? How can we as First Nations people develop contemporary structures that stay true to our values, culture, traditions and aspirations?

Our lives are framed by our houses. We reflect the places where we live, and those places reflect us. I’m hoping to counter the negative stereotypes attached to that and challenge misinformed perceptions. First Nations peoples simply do better when they have control over their own wellbeing.

Caroline Monnet is a Canadian First Nations (Anishinaabe, also known as Algonquin) and French artist. Caroline Monnet: Ninga Mìnèh is on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until 1 August 2021

This article was featured in ICON’s Summer 2021 issue. Read the digital edition for free