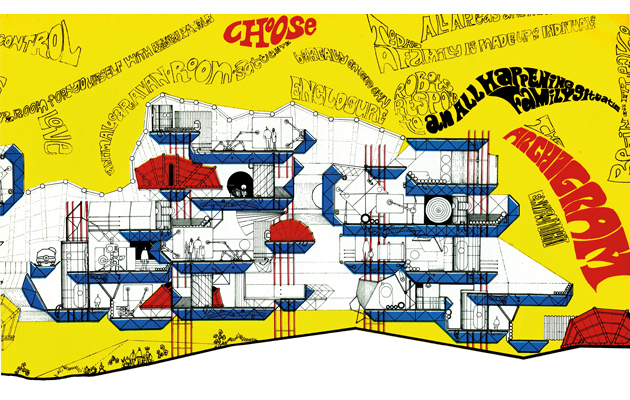

Control and Choice Dwellings, Part Section, Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, Ron Herron, Archigram 1967. Photo: Archigram Archive

Control and Choice Dwellings, Part Section, Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, Ron Herron, Archigram 1967. Photo: Archigram Archive

Commercialisation and the digital smog means we keep turning to the past and its radical visions of the future, argues Jay Merrick.

Do you suffer from dry, intellectually flaky existence? At a loss for words or ideas while ordering your Aperol spritz, or saying ‘yeah-yeah-yeah’ quite often, for no apparent reason? What you need is an easy-to-apply creative manifesto, an idea-rich moisturiser that will ensure your intelligence remains smooth, and so much more than merely skin-deep.

And, look, here’s just the thing! Archigram: The Book (reviewed on page 110). It’s big, it’s brand new, it’s lavishly produced, and it contains jolly interesting ideas. You immediately want to rub it in, don’t you? No, wait, on second thoughts, what if it’s just a placebo to salve your desperate need for securely packaged creativity?

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to think about the future of architecture, places and lives in ways that seriously challenge the status quo, or that don’t automatically default to musings about AI, robotics or other tropes of Facebook’s original motto, Move Fast and Break Things. Are we turning to historical architectural visions of the future – non-commercial jolts of imagination like Archigram’s – as an antidote to the commercialised travesties of faux-radical architecture and design?

It appears that the very idea of the future has become boring, as per the novelist JG Ballard’s vitriolic complaint: ‘I would sum up my fear about the future in one word: boring. And that’s my one fear: that everything has happened; nothing exciting or new or interesting is ever going to happen again. The future is just going to be a vast, conforming suburb of the soul.’

That suburb is a new kind of Twilight Zone in which most of us float like Major Toms in the zero gravity of multi-layered distractions – flickering, monetised visionettes shadowed by Rem Koolhaas’s remark: ‘Identity is the new junk-food for the dispossessed.’ Compare our horror vacui zeitgeist with the Dalek-cadenced clarion call of one of the 20th century’s greatest architects, Mies van der Rohe: ‘We reject all aesthetic speculation, all doctrine, and all formalism. Architecture is the will of the age conceived in spatial terms. Living. Changing. New. Not yesterday, not tomorrow, only today can be given form.’

Today, nearly a century after that properly radical declaration, only the past can be given acceptable form because our views of the present and future are shrouded in a digital smog whose choking density doubles every two years. Since 2005, the volume of data in existence has grown by a factor of more than 200, to roughly 40 zettabytes (that’s 21 zeros). According to the International Data Corporation, less than one per cent of this digital data is analysed. Are we beginning to suspect that we know virtually nothing about virtually everything? This awareness is insidious and fundamentally pacifying. We cling increasingly to evidence of the past, which tends to stifle any instinct for experimentation unless it’s related to consumption.

This commercialisation of iconoclastic ideas is evident in even the most radically-minded designers. In 2000, for example, Zaha Hadid Architects’ avant garde status was founded on manifestos that spoke of ‘a new phenomenology, navigation, and inhabitation of space’, and ‘the new ontology defining what it means to be somewhere’. In 2018, a press release about ZHA-designed sportswear told us that it ‘combines bio-centric Organic Bodymapping with material innovation and design expertise to deliver exceptional climate control and natural freedom of movement for all sports activities’. For around £80, you too can become a radically elasticated ontological phenomenon – a walking, talking, lifestyle manifesto.

To avoid these satires I confess that I, too, resort to the past – for example, by sampling the idea-rich readingdesign.org website, which reminds us that there have been times when design manifestos and ideas ran very distinctly against the prevailing grain. There is a strange purity to the process of reading and thinking about ideas which are not supported with imagery. When was the last time you encountered a vision or critique of the future that wasn’t simply some trope of gee-whizzery? Where are the troublemakers? Where are the proposals – think of Superstudio’s shocking negative utopia, a world covered by grids of impossibly vast concrete slabs – that jar us into really thinking about the meanings (or non-meanings) of space and form?

This remark by the social psychologist Nicolas Fieulaine in the Danish academic magazine, Scenario, seems particularly resonant: ‘We are caught in a present where we find it difficult to build a narrative about the past and imagine the future. We either adapt to a new fundamental uncertainty, or we become a culture that lives in opposition to the uncertainty …’ It appears that we are becoming terminally afraid, or unable, to think about the future in constructive ways.

Because today’s visions of the future are so dull,

writes Jay Merrick