|

|

||

|

The brute is back – on television, on social media, in coffee-table books, even in new buildings. But can we ever recapture the movement’s original spirit, asks Douglas Murphy? It feels so odd to say this, but brutalism is the very height of fashion. Everywhere you look in architectural media, it’s concrete, concrete, concrete. This has been murmuring around for a while now, with aficionados keeping the flame alive even in its darkest hours, but recent years have seen an explosion of interest. In books, there’s Elain Harwood’s mammoth Space Hope and Brutalism, Barnabas Calder’s Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism and Christopher Beanland’s Concrete Concept: Brutalist Buildings Around the World, to name just three published within the last year. There are events and exhibitions: Assemble’s Brutalist Playground recast the ludicrously non-health-and-safety landscapes of play from housing estates in colourful bouncy foam, while the National Trust of all people recently offered Brutal Utopia tours of Park Hill, the Southbank Centre and the University of East Anglia. On television, Jonathan Meades got in there early with his 2014 series Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloody-Mindedness (in which I got a very brief mention), while a surprisingly sympathetic Department of Culture, Media and Sport has been listing buildings – including Preston Bus Station – that previous administrations would have rushed to demolish. If your home needs decorating, there’s the modernist crockery of People Will Always Need Plates, or Zupagrafika’s Brutal London cut-out ornaments, but with enough cash swilling around you can get more involved. The Modern House is an estate agent dealing in post-war modernism, and brutalism is one of its specialities – it’s even got a book out – while Stefi Orazi’s Modernist Estates website charts the availability of the UK’s modernist housing stock. She’s got a book too (to which I contributed). If you’re very rich and aren’t concerned about social cleansing, flats in buildings such as Ernö Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower are coming up, cleansed of social tenants and spruced up by Urban Splash (who are also now getting started on phase two of Park Hill). |

Words Douglas Murphy

Above: Jordanki concert hall in Torún, Poland, by Menis Arquitectos, completed in 2015 |

|

|

||

|

The UTEC Campus, Lima, by Grafton Architects: ‘a kind of man-made mountain’ |

||

|

And if you’re not already sick at the sight of timber-shuttered concrete, there’s always the internet: Michael Abrahamson’s Tumblr, Fuck Yeah Brutalism, is a consistently presented selection of all things post-war concrete, while Dezeen had a whole brutalism season in late 2014. Recently, graphic designer Peter Chadwick created This Brutal House, a Twitter account serving up a seemingly endless stream of photos of concrete stuff, which in just over a year netted him a book deal with Phaidon for This Brutal World. Last but not least, there is Paul Rudolph, home to 30,000 members (including some pretty famous faces), and an endless stream of uploaded images of everything from nuclear bunkers to dilapidated bus stops.

The three towers of the Barbican Estate in London by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, completed in 1973–76 By this point, it’s clear that we’re a long way from the past. The images that interest brutalism fans now have almost nothing to do with Alison and Peter Smithson, with Reyner Banham, or with the origins of the term in the 1950s. Nobody seems concerned much about the pop-art sensibility that originally animated brutalism, or the collage technique of using materials ‘as found’ (and not just the grey stuff). Frequently, no one can be bothered even getting the architects right. The Brutalism Appreciation Society is at times an endless shouting match between those trying to apply at least some criteria to the submissions (‘This has nothing to do with brutalism!’), and those who just want to see pictures of anything whatsoever made of concrete (‘I like it because it looks brutal!’). It’s a historian’s nightmare. |

||

|

Jonathan Meades on Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation

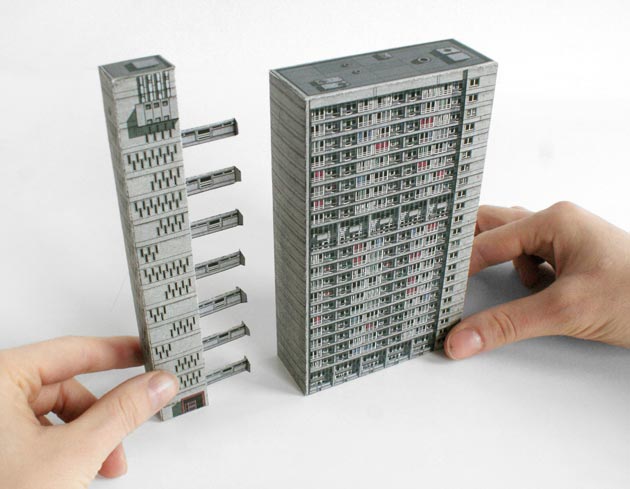

Zupagrafika’s Balfron Tower |

||

|

But does this really matter? It does, in the sense that brutalist architecture was frequently an expression of a particular social order, the varying types of Western social democracy after the war, and this is why for many it all appears to come from a far more advanced civilisation than the one that builds shiny but inane oligarchs’ architecture all over the world. This is also why, even in the midst of all this interest, David Cameron can still get points for promising to demolish ‘brutal’ housing estates – to many people it still reeks of socialism. But most of the people engaging with brutalism online aren’t interested in all that: for them it’s about bold sculptural form, the play of light, and, most of all, texture. In a world where architecture is mostly wafer-thin curtain walls or brick slips, the thickness and roughness of brutalism is catnip.

Brutalist memes But if it’s so very hot right now, could we see this brutalism wave make a difference in terms of actual buildings? On the one hand, it’s not as though concrete stopped being used at the end of the 1970s, and in various parts of the world – Japan, or South America – concrete-faced buildings are still acceptable, even if the approaches have changed. But building is a slow process, and we might just be seeing the beginning of brutalist aesthetics entering the mainstream again. Take the new Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of La Laguna, Tenerife, designed by GPY Arquitectos, a low-rise building with long, snaking corridors linking studio spaces, looped around three round courtyards. This plan is very contemporary – curved and with a diagrammatic clarity that brutalism never really possessed – but the look of the building has a very familiar and somewhat nostalgic effect. Wrapping round the curved exterior are long continuous ribbons of that quintessentially brutalist material known as ‘corduroy concrete’, bush-hammered favourite of Paul Rudolph, and one that has barely been seen on a new building in almost 50 years. |

||

|

Brunswick Centre by People Will Always Need Plates

Assemble’s Brutalist Playground |

||

|

This passion for abrasive texture is taken to the next level by Spanish architect Fernando Menis in the Polish town of Torún, where it has recently completed a concert hall. Formally, again, the design has little to do with the practice of the 1950s to 70s, being much more of a faceted, geological ‘decon’ type building (although it has hints of Gottfried Böhm), but the materials tell a different story. The board-marked concrete that makes up much of the exterior is one thing, but most of the building is clad inside and out with a skin literally made up of smashed bricks. The architect claims that this ‘recalls the facades of the old town’, but at the same time it’s dredging up the primal, geological roughness of classic brutalist buildings. |

||

|

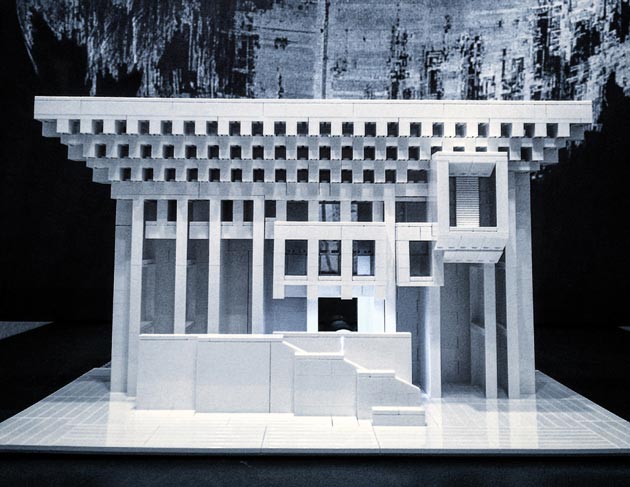

Boston City Hall in Lego by Arndt Schlaudraff

Concrete sculpture by Canadian architect David Umemoto |

||

|

But if these projects are contemporary with a nostalgic twist, there’s one building finished recently that really feels like a long-lost work from the most ambitious period of the mid-1960s – the new UTEC Campus in Lima, Peru, designed by Irish practice Grafton Architects. A long, curving megastructure swoops around following a main road, leaning back as it does so, with teaching spaces inserted within this massive frame, described by the architects as ‘a kind of man-made mountain’. Circulation happens through the voids in the structure, an arrangement that’s practical thanks to Lima’s year-round warm temperatures – the arrangement of staircases, walkways, floating beams and hanging gardens for once fully merits the term ‘Piranesian’. This spatial drama, the boldness of structural expression, the firm, chunky concrete detailing, it’s all high-brutalist in the best possible way. |

||

|

Faculty of Fine Arts, University of La Laguna, Tenerife, designed by GPY Arquitectos |

||

|

Of course, most of this new interest in brutalism is just frivolity, and a full-blown pomo-revival has been threatening to happen for the last five years at least. You could say that this is just the passage of time, and just as Victorian design made it back into the public’s affections, so the brutalism that’s still left will be appreciated, and so on forever. But this is an ahistorical way of looking at it. Brutalist aesthetics may well make a return in the (concrete) flesh, but if they do it will be in a way fundamentally contradictory to the original spirit. Back then, designers did look to the past, but almost always abstractly, and they worked facing towards the future. If today we don’t feel part of something genuinely new, and positive, all we can really do is sift through endless floods of imagery for inspiration, and who can blame us for being hungry for the rough stuff? Does brutalism’s new-found popularity gloss over its original intentions? Tell us on Twitter or share your brutalist photos with us on Instagram. This article first appeared in Icon 155

GPY Arquitectos’s Faculty of Fine Arts in Tenerife is characterised by long, snaking ribbons of bush-hammered concrete |

||