An Extinction Rebellion protest. Photo by Kevin Grieve via Flickr

An Extinction Rebellion protest. Photo by Kevin Grieve via Flickr

A new book explores how protest movements increasingly turn to branding techniques to get their message out – and, more importantly – get people to take to the streets. It’s an interesting and timely read, finds Peter Smisek.

There really could not be a better time for a book about the aesthetics of protest to come out than late 2019. While pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong have dominated the headlines for months, seemingly without end, other protests movements kicked off in Chile, Lebanon, and closer to home, with climate-focused Extinction Rebellion (XR) starting in London this summer. Elsewhere, protests fuelled by genuine and unresolved grievances from last year continued with a general strike in Catalonia, anti-corruption strikes in Czech Republic, and various ‘Resistance’ movements in the US.

In Branded Protest, Ingeborg Bloem and Klaus Kempenaars dissect some of the world’s most recent and current social movements and the way in which they use visual signs and disseminate their message using tools usually reserved for marketing agencies. And while the authors admit that it could be seen as problematic to view protest through the lens of commercial design, they make the case that some of the most compelling movements, and moments, were, in fact designed.

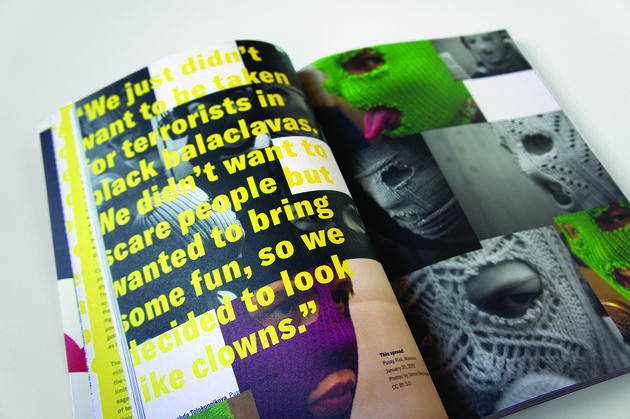

One of the chapters in the book is devoted to Pussy Riot.

One of the chapters in the book is devoted to Pussy Riot.

The logo for Je Suis Charlie, the outpouring of solidarity after a terrorist attack on the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, found its graphic logo courtesy of graphic designer and music journalist Joachim Roncin who made and posted his tribute quite spontaneously after the attack. Some movements develop much more professional, deliberate strategies, especially in the US where Black Lives Matter and Women’s March developed almost brand identities that were needed to mobilise support across the world’s fifth-largest country. Attention is also paid to the eye-catching installations and art performances deployed by XR and the 2014 Umbrella protests in Hong Kong. ‘Legacy’ charities such as Peta, Amnesty International and Greenpeace get a look-in and it is interesting how the emphasis of their campaigns shifted over time. The chapter on the Rabia sign makes for particularly dark reading.

Each protest movement/group is explained in a different way. Sometimes through essays, such as the short chapter dedicated to the chaotic and enigmatic Anonymous, and in some cases through interviews, or, in the case of larger, more important movements, both. This more tailored approach to the text gives the book a refreshing quality. There are a few pitfalls – sometimes the protest movements are perhaps not questioned hard enough – XR, for instance, for all the visual spectacle, has been regularly dismissed as overwhelmingly white and middle-class artsy ‘crusties’ by the right-leaning British media, and it would be interesting to see how these critiques are either absorbed or rejected.

For all the effort dedicated to sophisticated visual identity and dissemination, turning up still matters. Photo by Fibonacci Blue

For all the effort dedicated to sophisticated visual identity and dissemination, turning up still matters. Photo by Fibonacci Blue

But for all the visual pizzazz, well-meaning slogans and dissemination techniques, most of the interviewees, as well as the writers seem to agree that turning up and taking a physical stand still matters. In a world where misinformation can spread more easily, presence in the streets is more important than ever.

Branded Protest is available from BIS Publishers