|

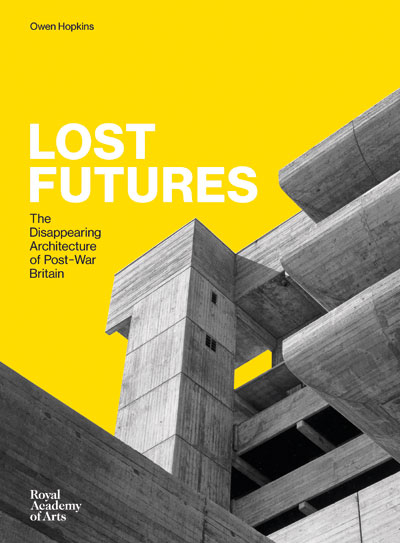

Owen Hopkins provides a welcome antidote to the histrionics and heroising that blight our understanding of modernist architecture, says John Jervis Published in 2009, Owen Hatherley’s Militant Modernism was a self-professed diatribe. Necessary and persuasive, it defended the often derided ideals and achievements of British modernism, particularly in its Banham-approved brutalist guise. Yet its influence on architectural writing since has not been entirely positive. As Owen Hopkins puts it in Lost Futures, his new book for the Royal Academy, imagery of shuttered concrete has ended up as a fetishistic ‘currency of cool’ for social media cliques such as Facebook’s Brutalism Appreciation Society, indicating ‘a vague and suitably non-committal alignment with leftist politics’. Context has been abandoned for preening. To be fair, this cult of concrete has at least popularised brutalism in some circles, aiding the listing of Preston Bus Station, Sheffield’s Moore Street substation and Metro Central Heights. More tiresome is the sanctimony of a self-appointed political hardcore, who see brutalism as the embodiment in form and spirit of the welfare state, wielding it as a cudgel against the abandonment of treasured postwar ideals. Little does it matter that the peak of social housing in the early 1950s coincided with the tasteful brick of Woodberry Down. Tea‑towel favourites such as Trellick Tower and Robin Hood Gardens made their beleaguered, brutalist appearance 20 years later, by which point a precipitous decline in council housing was well underway, and the last vestiges of white-heat optimism had been extinguished. Against this background of claim and counterclaim, Lost Futures is a blessed relief, free from the sound of axes being ground. The accompanying exhibition boasts a rather affected title – Futures Found: The Real and Imagined Cityscapes of Post-War Britain – but the book itself is an old-fashioned curatorial summation of current understandings of postwar public and commercial architecture. Its incisive, informed introduction is followed by a strong collage of entries on 35 demolished or threatened buildings. Each is illustrated with evocative contemporary photography from the Architectural Press, which presents them at a moment of hope, even expectation. The accompanying texts are denuded of histrionics, prioritising construction, conservation and economics as much as politics, and retain an admirably even tone, even when such tempting targets as Alice Coleman – the estate guru beloved of Margaret Thatcher – or the painful demolition of Imperial College’s Southside Halls of Residence present themselves. Some projects tick very familiar boxes – Ronan Point, Balfron Tower, Centre Point – while housing, predictably, dominates, from Basil Spence’s Hutchesontown C in the Gorbals to James Stirling’s Southgate in Runcorn New Town. The latter subject is perhaps too complex for the allotted 350-word descriptions – regional variations, vagaries of taste, budgetary squeezes and the subtleties of local and national politics tend to be rubbed away. In addition, to be told over and over that later problems in each housing estate can be ascribed to economies of construction and maintenance (or to oil-fired communal heating) suggests a mantra rather than a meaningful explanation. We should just accept that not all postwar estates were created (or designed) equal. Total honesty still seems too painful when discussing why quite so many fell into deep trouble within a handful of years. The architecture of the National Health Service is absent – an oversight given the premise of the exhibition – yet otherwise Hopkins’s choices are eclectic and engaging. Owen Luder’s Tricorn Shopping Centre in Portsmouth is accompanied by two of the book’s most striking images, yet it is clear that Britain’s postwar malls – and particularly those that attempted to incorporate other typologies – were soon struggling to adapt to changing retail requirements. Similarly, Mondial House, the marvellous polyester-clad telephone exchange alongside London’s Cannon Street Station, lasted just 30 years before its technology became obsolete. The greatest pleasures come from unexpected diversions, whether Coventry’s ethereal-cum-elephantine Fairfax Sports Centre, or John Madin’s Miesian Birmingham Post & Mail Building (as Hopkins notes, an astonishing contrast to the Central Library a decade later). Excursions to the demolished Dover Stage Hotel by Louis Erdi – an early offshoot of cross-Channel tourism, with pioneering use of V-shaped pilotis – or to the burgeoning restaurant trade, as at Patrick Gwynne’s revered Serpentine Restaurant in Hyde Park, prove particularly rewarding. Similarly, the inclusion of Frederick Gibberd’s Hinkley Point A reinforces the intimate relationship between built environments and political and economic fortunes, as evidenced in Britain’s awkward, expensive efforts in the deeply contested and uncertain world of nuclear energy and weapons. Although the black-and-white photos in Lost Futures are infused with nostalgia, that of Birmingham Central Library at its 1974 opening is also notable for its crumbling road surfaces: a salutary reminder that time had long since run out on the modernist dream. At heart, despite its measured tone, this book cannot avoid being a lament for lost ideals and their flawed embodiments. A slipping of the mask is forgivable when Hopkins describes how, from the 1980s on, ‘schools, libraries, public buildings, even factories, which a generation or two before had been designed and built as expressions of collective or civic values, were derided as concrete monstrosities to be razed from the face of the earth’. Such regrettable recent losses as ABK’s Redcar District Library or John Bancroft’s Pimlico Secondary School certainly throw into stark relief current redevelopments that prioritise one-off financial returns on public assets. Missed opportunities echo throughout the book’s pages – short-sighted decisions by politicians, local councils, businesses, architects, perhaps even communities. Such failure of vision is often an even greater issue than the merits or demerits of the original structures on the sites. The text includes its share of scathing quotations, whether James Stirling asserting that the ‘lethal combination is not so much the architect, the lethal combination is the town planner, and the local council and the idea of progress’, or Kingsley Amis on architects’ ‘unique power of sodding the consumer at a distance’. It is Hopkins, however, who may put a few noses out of joint with his claim that brutalism, once ‘the most confrontational of postwar styles’, has now been entirely sanitised: ‘surely evidence of how its buildings and the values they embody are no longer deemed to pose any kind of challenge to the status quo’. And he does get carried away during a lengthy digression into the tacky claddings and pasted-on lobbies of 1990s private-finance modernism and Cool Britannia’s neglect of 1960s architecture. Drawing a societal arc from collective to individual, and from state to market, he even speculates that a third great epoch of post-war history may now be upon us. Modernism aspired to shape a better society, as Hatherley pointed out back in 2009. Rather than endless tussles about its supposed naiveties, arrogances or betrayals, a careful assessment of the political, social, economic and architectural reasons behind its short-lived and very mixed success – particularly in Britain – is much needed. Such a project would be a far greater challenge and achievement than yet another clumsy appropriation of concrete as a proxy in today’s political battles. Architectural writers need to accept that postwar architecture is now history, and if we are indeed to ‘learn lessons’, we need to research and understand it as such. It is to Hopkins’s great credit that, by and large, he succeeds in this admirable first attempt.

|

Words John Jervis |

|

|