|

|

||

|

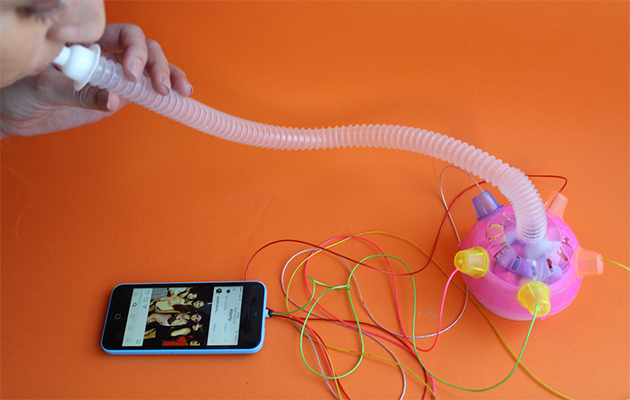

The sixth edition of the Lebanese festival was in many ways the anti-Milan, says James McLachlan Is design a need? That was the question posed this year at Beirut Design Week. The provocation is, of course, deliberate. Design is a need, surely. ‘We wanted to shock people a little bit,’ explains co-founder and director Doreen Toutikian. ‘To get them thinking, why on earth are they asking this question?’ A former designer, Toutikian is interested in questions as much as answers. Unsurprising then, that the show is a world away from the standard trade fair jamboree of product launches augmented by a couple of corporate-sponsored installations. The energetic and seemingly chaotic entity that is Beirut itself only serves to sharpen the sense that this is alternative – the anti Milan. Now in its sixth year, this edition of Beirut Design Week is an intensely personal project – the theme is an extension of Toutikian’s master’s dissertation – and the week began with a number of writers, critics, designers and thinkers interrogating the aforementioned question at a day-long conference held at the Sursock Museum. Thought-provoking (and occasionally heavy-going) it pushed to the forefront an aspect of design that more often than not is confined to academia. It set the tone for the rest of the show and chimed with Toutikian’s vision for a Beirut Design Week free from what she sees as the asphyxiating grasp of the corporate world. In the past, she explains, the focus had been on attracting big-name European designers, but that strategy didn’t prove to be a good way of highlighting homegrown talent, who were overshadowed by the gala names. ‘Honestly, they think so little of us. They are not here to see Beirut and what we are doing – they just think we are a poor country, war-torn or whatever, and they are going to fly in, make some money and fly out again. That goes against everything I wanted.’ And so, instead of looking to Europe, Toutikian reached out to peers in Cairo, Tripoli and Dubai bringing them together in the KED – a five-floor former metallurgy warehouse occupied by militia during the civil war and refurbished as an exhibition space in 2016. Much of the work on display explored the idea that design can be used as critical tool reflecting our misgivings about society, politics and culture and realizing them as 3D objects. Speculative Needs by the Mena Design Research Centre brought together more than 100 students across a variety of disciplines from five Lebanese universities, who proposed solutions and critique for a fictitious, but at times plausible, future – products such as Cyberprison, a device that prevents anyone convicted of a cybercrime from receiving an internet signal and the Eat Yourself rehydration tool that harvests water from the atmosphere and feeds it directly into the body. The students were clearly encouraged to have fun with the brief and extracted a good deal of humour from their own millennial angst. FOMO (Fear of missing out) Breather, for example, calms the nerves of those not invited to the party while a series of messages from the future deals with hypothetical problems of tomorrow’s teenagers: ‘OMG, I can’t believe I am going to miss your party because Dad wants me to stay home for his dead great, great grandmother’s birthday!’ By sourcing ‘componentry’ in shops selling cheap plastics toys, the aesthetic across all the products was surprisingly unified. There were other highlights, this time using more time-honoured materials. Karma Dabaghi Design Studio, for example, tackled the grieving process with a sequence of poetic marble sculptures marking the different emotional stages. For Nationmetrix, architects Roula Salamoun and Ieva Saudargaite cast the net wider, with a discombobulating installation that suspended a forest of plastic pipes from the ceiling and inviting visitors to navigate their way through it while pumping in instructions and noises. The aim was to interpret the often-restrictive experience of travelling on a Lebanese passport. There were other, even odder, exhibits. I may have been alone in misunderstanding the immersive fashion experience, but I suspect not. Nevertheless, it made for a rich and diverse show that was anything but dull. Intentionally or not, the biggest question Beirut Design Week poses is more fundamentally existential: can a show like this, which has consciously moved away from courting big money brands, survive in the long term? I hope it can. Undoubtedly, the design world will be a less interesting place without it. |

Words James McLachlan

Above: Nationmetrix, an installation by architects Roula Salamoun and Ieva Saudargaite, evokes the often-restrictive experience of travelling on a Lebanese passport |

|

|

||

|

FOMO (Fear of missing out) Breather |

||