|

|

||

|

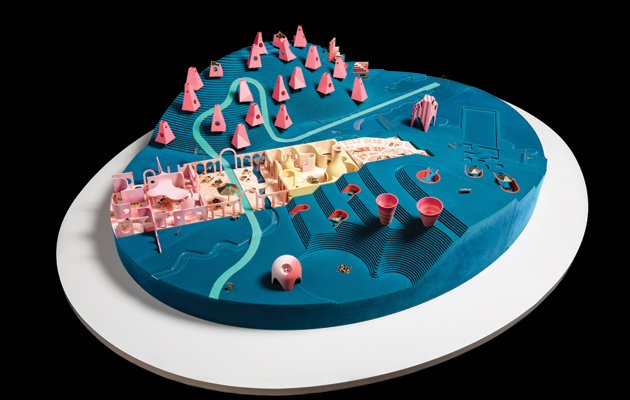

An exhibition in London tracing the history of psychiatric institutions, from the founding of Bethlem Royal Hospital to the modern day, refrains from imposing a strong curatorial voice – instead, it allows the stories to speak for themselves This is a risky exhibition. In four large rooms, how can you express all the diverse, complex and sensitive threads that could, and should, be drawn out from the painful story of Bethlem Royal Hospital, London, from its founding in 1247 right up to the present day? How can you touch on all the changes in society’s perception of mental health, and in the treatment of those deemed insane? How do you effectively reverse the gaze, giving these individuals the opportunity to speak for themselves, saving exhibition-goers from becoming modern-day equivalents of Hogarth’s foppish visitors to Bedlam, gawping at the Rake in his squalor? Curators Bárbara Rodriguez Muñoz and Mike Jay don’t attempt encyclopedic display, nor do they impose a strong curatorial voice. Instead, they use the framework provided by the physical and medical development of Bethlem to weave an affecting, if partial, tapestry. Specialists may well find gaps, but all but the most pernickety should still find pleasure. Architectural historians, for instance, will be frustrated by displays of rare imagery via cramped lines of glass slides – as elsewhere in the exhibition, impressions are prioritised over clarity. However, they will enjoy the panegyrics and prints that greeted the openings of Bethlem’s various homes, each praised as the long-awaited dawn of a new, humane era, before rapid descents into overcrowding and neglect. Robert Hooke’s flimsy construction at Moorfields (1675) concealed gloomy, cracked interiors behind its noble facade – parallels were swiftly drawn with society’s hypocritical treatment of the afflicted – but its demolition in 1815 led to mourning for ‘the only building that looked like a palace in London’. Another highlight is an immaculate architectural drawing of 1930 by Ralph Maynard Smith that shows the generous villa system pioneered at the new Bethlem in Monk’s Orchard, Beckenham. Those with expertise in definition, diagnosis and treatment are likely to have their own reservations. The cursory treatment of the County Asylums Act of 1808 is curious, while a 2010 reissue of RD Laing’s The Divided Self adds little to understandings of the 1960s anti-psychiatry movement. More problematic, however, is a reluctance to engage with theoretical discourse – most jarring given the abundant material relating to female inmates, but also disappointing given the show’s exclusively Western frame of reference. Symposium in blues, record sleeve, 1966. Wellcome Library, London Despite these caveats, an impressive range of stories is presented, such as the humane approach pioneered at the York Retreat, founded in 1796 by the Society of Friends, in which inmates undertook tasks such as churning butter and polishing furniture. Similarly, architectural plans and notes were submitted by James Tilly Matthews, an inmate of Bethlem since 1797, for the competition that preceded the 1815 rebuilding: his prescient efforts were rewarded with a small prize, but the open institution he envisaged, in which occupants tended gardens and cared for the sick, failed to materialise. There are contemporary artistic responses throughout the show, of which Eva Kotáková’s tense Asylum installation (2014), based on her visits to the Bohnice psychiatric hospital in Prague, is the stand-out. However it is the displays of visual art by patients that really grab the attention, whether well-worn (Vincent van Gogh and Richard Dadd) or lesser-known (Vaslav Nijinsky’s hypnotic Masks, created after his final break with Sergei Diaghilev in 1917, or work by Sergei Pankejeff, the ‘Wolfman’ of Freud’s famous case history of 1918). The most popular and moving exhibit in this vein is, however, unexpected. Abandoned Goods is a film detailing the pioneering art studio run by Edward Adamson at Netherne psychiatric hospital in Surrey from 1946 to 1981, which evolved from a diagnostic laboratory to a therapeutic tool that prioritised creative freedom. The contrast between the bleached footage of ordinary, blue-rinsed patients in institutional surroundings and the compelling collection of artworks that survives is powerful, and the connections created are very human. The exhibition’s distinct emphasis on patient art does, however, risk reviving the romantic conceit that mental illness, in its otherness, provides insights denied the wider world, a belief well established by the 18th century, and still perpetuated by elements of the Outsider Art movement today. The emergence of psychiatric drugs in the 1950s (represented here by such oddities as Symposium in Blues, a 1966 jazz compilation with Artie Shaw, Lead Belly and others, released to market Amitriptyline, as well as 1958 designs by Salvador Dalí promoting an early version of diazepam) proved a major challenge to the asylum system. However, it was the unlikely figure of Enoch Powell who signaled its end with his famous ‘water tower’ speech of 1961. The curators make a rare intervention at this point to defend the continued importance of community spaces today, aided by the utopian Madlove: A Designer Asylum (2014) installation by Hannah Hull and the Vacuum Cleaner, for which 432 people suffering from mental distress imagined an ideal institution, with results that include a room of Fabergé eggs available for smashing and David Attenborough as resident book-reader. Finally, by the exit is a flashy 2016 brochure for luxury flats at what was once Friern Hospital at Colney Hatch, now ‘Princess Manor Park’. The building’s original purpose is never stated amid grandiose claims about its ‘distinguished history’ and ‘Italianate splendours’, all of which ‘add dignity and exclusivity to modern life’. Associations with insanity are, it would seem, commercial poison. The suppression of mental health issues – the pretence that they are no concern of ours – remains a deeply rooted and damaging problem in society today, yet they are also becoming increasingly widespread. This show may be risky, but it is important. Bedlam: The Asylum and Beyond, Wellcome Collection, 15 September 2016 – 15 January 2017 |

Words John Jervis

Above: The Vacuum Cleaner and Hannah Hull’s Madlove – Designer Asylum, 2016, Design by Benjamin Koslowski and James Christian. Wellcome Collection, London |

|

|

||

|

Sergei Pankejeff, Painting of Wolves Sitting in a Tree, 1975. Courtesy of the Freud Museum, London |

||