|

|

||

|

In a time of financial disaster, there’s one exhibit in Bauhaus: Art as Life that really catches the eye. It comes from a room on the school’s 1923 switch from wild, utopian expressionism to sober, utopian constructivism. A collection, under glass, of million-mark banknotes, produced for the state bank of Thuringia by the great typographer Herbert Bayer. They might be the most uncanny banknotes ever produced, completely abandoning all the things that define banknote design to this day – no curlicues, serifs, signatures or etchings of historical notables. Instead there are primary-coloured lines and blocks, and stark, unromantic numbers, depicting in their austere way the effects of the hyperinflation that beset the Weimar Republic in 1923, bringing it to the brink of a communist revolution. These notes were fit to be used as insulation or kindling, but could hardly buy much in the way of food. Bayer, one of the Bauhaus’ most talented sons, is here trying to make something completely insane into something rational. Only a capitalism on its knees could ever have commissioned such a banknote. Little finds like this are what keeps the exhibition interesting. It may well be the largest show on the subject for 40 years, but even to the non-expert lots of the ground must be familiar from recent shows. Anyone who went to the Tate Modern’s Albers and Moholy-Nagy, the V&A’s Modernism or sundry others about the interwar avant-garde will know the territory. The focus in the Barbican is on the kind of life the Bauhaus created for its students and “masters”, and the kind of life it promised for the millions not enrolled at its successive homes in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin. So there are a lot of experiments by the lesser-known pupils of the famous names, some of them very surprising and, well, fun; in general there is a lot of partying and androgynous levity. Focusing on the Bauhaus’ joie de vivre fits a little oddly with Carmody Groarke’s exhibition space, which bisects the Barbican’s very un-international style brutalist-baroque into some clean-lined cubes and rectangles. The upper floor concentrates on the early expressionist years, when their ideal was a “Cathedral of Socialism” – some furious combination of the mysticism of Rudolf Steiner, the architectural ideology of John Ruskin and the anarchist theory of Gustav Landauer. It doesn’t explain how Walter Gropius, an architectural and political pragmatist both before 1914 and after 1922, managed to orchestrate something so heady, but steps suddenly into a world of machine-made objects and mass production. Then, downstairs, as we find the Bauhausler in their extraordinary constructivist building at Dessau, the bright lights switch on. The focus on joyful living through concrete and collage is an insightful way of looking at the school, but it comes up against the problem of museumification. In one room, a little girl was sketching some puppets designed by Paul Klee, which suggests the exhibition has done what it set out to do; but then, surely both a Johannes Itten and a Moholy-Nagy would have hated these untouchable objects under glass, and would have preferred objects you can touch and mould, not to mention tubular steel chairs you can actually sit on. In the shop – contiguous, as always – you can pay astounding sums for chess sets and building blocks that were meant to be cheap and mass-produced; but the banknotes or credit cards you pay with keep their cartouches. Financial irrationalism takes different forms nowadays.

credit Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

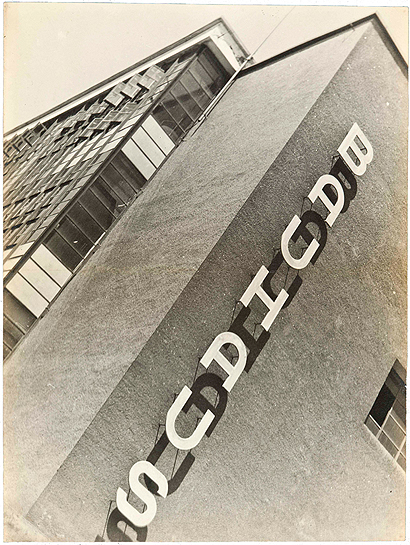

credit Galerie Berinson, Berlin/Makoto Yamawaki |

Image The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society, New York

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||